By Rima Najjar

During the time that Palestinians call The Great Rebellion or Revolt against British pro-Zionist policies in Palestine, 1936-1939, things began to go seriously wrong for Palestinian Arabs living in Jaffa and have continued to deteriorate with no reprieve yet.

Jaffa, at the time, was a major economic center in Palestine, a port and commercial hub. In the 19th century, Palestinian citrus farmers had introduced innovative grafting techniques to growing oranges, for which Jaffa is famous to this day – but with credit for its flourishing citrus industry going to Jewish usurpers rather than Palestinian Arabs.

In fact, the very existence of these Palestinian Arabs is often denied through Israel’s Zionist myth-making on hasbara sites.

By the 1930s, Jaffa’s flourishing citrus industry and exports had turned it into a major economic center, providing jobs for thousands and spurring the development of related economic sectors like banking, textiles, transportation, manufacturing, and tourism. Dubbed the Bride of the Sea, it was also a major cultural center.

The seeds of the Great Rebellion were sown when the League of Nations, in the “mandate” it issued to the British government over Palestine in 1922, included language facilitating European Jewish immigration to the country.

Life in Jaffa for Palestinians was affected in deeply horrific ways both during and after the Great Rebellion and during and after the Nakba of 1948, which Israel touts as “independence”, but which in reality is a conquest and colonization of Palestine by foreign forces, a fact that is ongoing to this day.

The bloody dispossession of Palestinians is referred to incorrectly and deceptively on the internet as a “civil war”. It’s what Google spits out in spades.

Palestinian Arabs naturally resented the massive foreign Jewish immigration that did, in fact, follow in Palestine in accordance with British mandate policies; they resisted the takeover of Palestine by the Jewish Zionist Movement, which was orchestrated from Europe.

Jaffa experienced a major violent disruption in 1936 when large sections (amounting to 220-240 buildings) of the Old City of Jaffa were blown up by the British military, ostensibly for “town-planning purposes”, but really as a punitive measure against the Palestinian rebellion.

Leaflets were dropped on Jaffa and its environs telling people to vacate their homes with the end result that 6,000 Palestinians were made homeless.

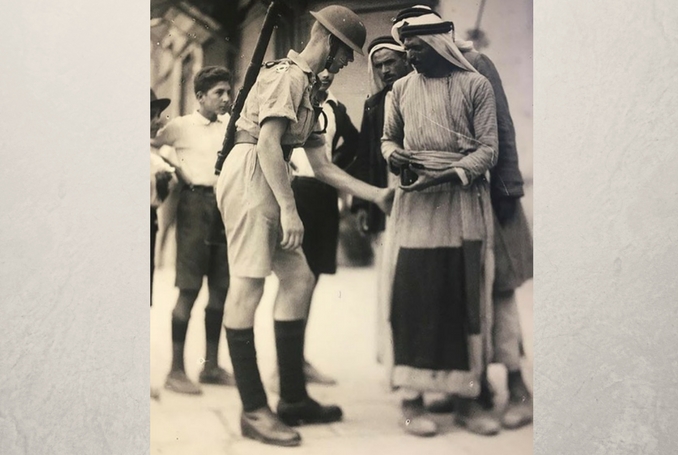

Life for these Palestinians during the Great Rebellion events deteriorated badly. There are many accounts of the devastating hardship of that time, including an account, for example, of a British policeman executing a Palestinian Arab in the Manshiya district of Jaffa, and of incidents of British troops robbing Palestinians – even children of their pocket money.

The Nakba events leading to the forcible establishment of Israel continued the destruction of the Palestinian social and economic matrix in Jaffa begun by the British as described above.

As early as the 1930s, myth-making depicting Palestine as a land empty of people was in progress.

“In the 1930s the Jewish painter Nahum Gutman painted a picture of the area between the Old Mosque in Jaffa and Tel Aviv as if it were empty, nothing but sand. He erased the Arab houses that were there from his vision, exemplifying the Zionist concept of an empty land, ignoring the Palestinians who actually lived there. In 1948 there were 100,000 inhabitants – Palestinian and Jewish – of Jaffa. Photos that show this do not appear in Israeli museums.”

In 1931, the population of Jaffa was 44,638 Palestinians (i.e., non-Jews) and 7,209 Palestinian Jews.

Under the 1947 UN Partition Plan, Jaffa was to be part of an Arab state. However, Jewish terrorist forces (the Irgun) and Haganah militia mounted a siege on Jaffa, effectively cutting it off from the rest of Palestine, and indiscriminately shelled the Palestinian population with mortars for four days and nights in April 1948.

Israeli research such as that by Amiram Gonen speaks of the emergence of “a geographic heartland” after the Nakba in Jaffa and Tel Aviv.

But the fact is, after the establishment of Israel as a Jewish state on a partitioned Palestine in 1948, life in Jaffa for a huge number of Palestinians became non-existent, for the simple reason that they were forced out of the city and denied return. The British tried to protect Palestinian Arabs from being evicted in Jaffa and failed, handing over their military bases to Zionist forces.

Today, Jaffa refugees and exiles are scattered in the West Bank and all over the world, but they haven’t forgotten the life they lived there before the Nakba.

As one example, as much as 80% of the population of Balata refugee camp in the West Bank, east of Nablus, is originally from Jaffa. It is a camp meant to hold 5000 refugees but is now more than 27,200 Palestinians strong and is known as a symbol of resistance.

Only 30% of the population of Jaffa today is Palestinian Arab. It is a story worth retelling and remembering repeatedly because it continues to be buried under an avalanche of Israeli hasbara.

“The expulsion of the Palestinians – not merely the fighters but the civilians – had been well prepared. Throughout the 1930s and 40s, dossiers on all the Palestinian villages had been meticulously compiled by Zionist militias and stored in the files of the Haganah (the Zionist military organization that operated during the time of the British mandate, 1921-48, after which it formed the basis of the IDF). These files can still be consulted today in the Haganah archives (see Pappe, Ethnic Cleansing, passim).

“The Haganah sent spies into the villages, where they availed themselves of the Arab hospitality offered them and, under the pretext of concern for the wellbeing of their hosts, inquired about the number of animals and the amount of land each family owned. This information came in useful when half the villages of Palestine were destroyed in the Nakba. No doubt it also formed a database for the ‘Great Book Robbery’ that took place at the same time, when 70,000 volumes were stolen from well-to-do Palestinian homes and from mosques, some of them to be pulped as being ‘hostile’ to the new Israeli state, and others ending up in the National Library with ‘AP’ (abandoned property) embossed on their spines.”

For those Palestinians who remain, life in Jaffa today, as Sami Abu Shehadeh and Fadi Shbaytah write below, is grim:

“The story of Jaffa’s ongoing Nakba is the story of the transformation of this thriving modern urban center into a marginalized neighborhood suffering from poverty, discrimination, gentrification, crime, and demolition since the initial wave of mass expulsion in 1948 to the present day.”

The life of Palestinians in Jaffa (and other Palestinian cities and towns) during the British Mandate has been documented (and illustrated through photographs from the time) in a wonderful book edited by historian Walid Khalidi titled ‘Before their Diaspora.”

[For those interested in this topic, Khalidi’s book has been made available online for free by The Institute for Palestine Studies]

– Rima Najjar is a Palestinian whose father’s side of the family comes from the forcibly depopulated village of Lifta on the western outskirts of Jerusalem. She is an activist, researcher and retired professor of English literature, Al-Quds University, occupied West Bank.