By Rod Such

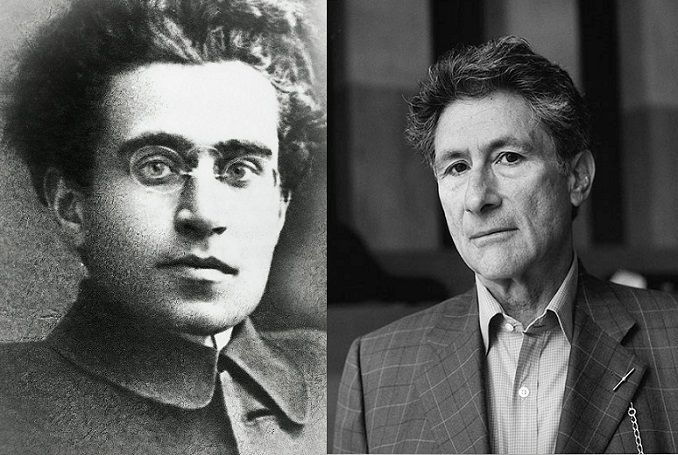

The prominent Palestinian intellectual Edward Said, author of Orientalism and The Question of Palestine, admired the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci for his views on cultural hegemony. What might have transpired if these two intellectual giants were able to collaborate on strategy and tactics for the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement launched by Palestinian civil society in 2005, two years after Said’s death and 68 years after Gramsci’s?

This essay explores Gramsci’s concepts of moral leadership, common sense and good sense, cultural hegemony, superstructure, “taking inventory,” “war of position,” and the philosophy of praxis, their influence on Said’s thinking, and their relevance to the BDS movement. Underpinning this exploration, I seek to answer whether a Marxist or socialist perspective on BDS is even needed, let alone desired. Why is it not enough that socialists simply answer the call of Palestinian civil society and find ways to support the BDS movement in practical activity? Does Marxist theory contribute anything of importance to this movement? The conclusion reached is that both Gramsci and Said left behind a legacy that provides invaluable insights and reasons for why and how BDS can succeed in Western capitalist countries, particularly the United States, and become part of a global Intifada that works in tandem with Palestinian resistance on the ground in Palestine.

Marxism is unique as a philosophy that goes beyond merely interpreting the world by announcing that its intention is to change the world. This essay, therefore, also explores a three-year-long BDS campaign in Portland, Oregon. The goal is to determine if the Gramscian-Said legacy might have helped guide it. A dialectical relationship exists between theory and practice in which neither is complete without the other. Theory guides practice, and practice in turn deepens, corrects, and enriches theory. Theoretical precepts, according to this view, must be tested in the laboratory of human activity.

Gramsci’s concept of “moral leadership” is apt in this context. For Gramsci the working class was “economist” if it spoke only for itself. He urged Italy’s Socialist Party and later its Communist Party to take up the “Southern Question”—that is, the plight of the peasantry, particularly in the less-industrialized southern part of Italy. But Gramsci was not content with just a worker-peasant alliance. He called for the working-class parties to provide “moral leadership” for all “subalterns,” who he defined as anyone in a subordinate position in capitalist society or what today we would call the 99 percent.

Similarly, in his book Orientalism Said stakes out a viewpoint of moral leadership in his underlying theme of challenging the way Western colonialism and its literature dehumanized and denied agency to colonized peoples. Said’s critique of the West’s conception of the Orient is ultimately based on a radical understanding and rejection of the notion of superior cultures, placing the “Orientalist” framework firmly in the context of colonialism and imperialism.

Gramsci’s notions of common sense and good sense are intimately linked to his idea of cultural hegemony and superstructure. For Gramsci the advanced capitalist countries enforced their rule and control not just through the repressive state apparatus—the police, the courts, the prisons, the military—but also through the institutions that emerge in civil society. The state apparatus is primarily based on force and coercion to maintain capitalist rule while institutions of civil society—ranging from trade unions to churches to the media to what we call today nongovernmental organizations—often help manufacture consent with the established order of things rather than challenge that order.

The notion of cultural hegemony derives in part from Marx’s famous dictum in The German Ideology: “The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force.”

Gramsci pondered why workers succumb to these ruling ideas when their class interests are diametrically opposed to those of the capitalists. He invoked the ideas of common sense and superstructure to explain how ruling class ideas establish hegemony over society at large and make it seem as though the capitalist order is merely the common sense outcome of human affairs.

In a sense Gramsci anticipated by nearly 100 years Thomas Frank’s exploration in his best-selling What’s the Matter with Kansas of why voters in the state of Kansas, once a center of abolitionism and agrarian socialism, voted against their own economic interests by embracing the Republican Party’s social agenda.

To establish this cultural hegemony and to keep it functioning smoothly, the ruling class also helps sustain a superstructure, such as the academy, civil society organizations, and the media, to ensure that its ideas remain supreme. The chief architects of “common sense”are our media and academic pundits who manage to disguise or obscure the systemic nature of capitalist oppression and exploitation. People learn to embrace and accept ideas contrary to their own interests because they are surrounded daily by a virtual gestalt of hegemonic ideas that must be true because seemingly everyone believes them to be true. To be controversial is to be dissident, an outlier from the established order of common sense.

In The Question of Palestine and The Politics of Dispossession, Said deconstructs the “common sense” ideas that have buttressed the Israeli narrative for decades and made the existence of a Jewish state seem reasonable to many people. These include the argument that the crimes of the Holocaust left the Jewish people with no alternative but to establish a Jewish state of their own for their own protection and refuge. Palestinian resistance to Zionist displacement in the “common sense” narrative then became simply a continuation of the persecution of the Jews. Israel became heroic David to the Goliath of surrounding Arab countries, according to this hegemonic narrative.

To counter this narrative, Said applied “good sense,” as opposed to the prevailing “common sense,” unerringly dissecting every hypocrisy, lie, and contradiction within the Israeli narrative by showing how they contravened established ideas of human rights and democracy. In doing so, Said, along with many others, established the Palestinian narrative as a hegemonic alternative to the dominant paradigms.

In Orientalism, Said acknowledges the influence of Gramsci, calling out in particular the distinction Gramsci made between civil society and state institutions and the role played by civil society in establishing cultural hegemony. Said writes:

“Gramsci has made the useful analytic distinction between civil and political society in which the former is made up of voluntary (or at least rational and noncoercive) affiliations like schools, families, and unions, the latter of state institutions (the army, the police, the central bureaucracy) whose role in the polity is direct domination. Culture, of course, is to be found operating within civil society, where the influence of ideas, of institutions, and of other persons works not through domination but by what Gramsci calls consent. In any society not totalitarian, then, certain cultural forms predominate over others, just as certain ideas are more influential than others; the form of this cultural leadership is what Gramsci has identified as hegemony, an indispensable concept for any understanding of cultural life in the industrial West. It is hegemony, or rather the result of cultural hegemony at work, that gives Orientalism the durability and the strength I have been speaking about so far.”

Said was also particularly taken with another concept of Gramsci’s—the idea of “personal discovery” and “taking an inventory” of one’s own subjectivity and conditioning due to one’s historical circumstances. As we’ll see, this is also of particular relevance to the BDS movement. In another passage in Orientalism, Said writes:

“The personal dimension. In the Prison Notebooks Gramsci says: ‘The starting-point of critical elaboration is the consciousness of what one really is, and is ‘knowing thyself’ as a product of the historical process to date, which has deposited in you an infinity of traces, without leaving an inventory.’ The only available English translation inexplicably leaves Gramsci’s comment at that, whereas in fact Gramsci’s Italian text concludes by adding, ‘therefore it is imperative at the outset to compile such an inventory.’ Much of the personal investment in this study derives from my awareness of being an ‘Oriental’ as a child growing up in two British colonies. All of my education, in those colonies (Palestine and Egypt) and in the United States, has been Western, and yet that deep early awareness has persisted. In many ways my study of Orientalism has been an attempt to inventory the traces upon me, the Oriental subject, of the culture whose domination has been so powerful a factor in the life of all Orientals. This is why for me the Islamic Orient has had to be the center of attention. Whether what I have achieved is the inventory prescribed by Gramsci is not for me to judge, although I have felt it important to be conscious of trying to produce one.”

Said admittedly was not a Marxist and even criticized Marx for succumbing to Orientalist ideas himself. At the time of writing Orientalism, the influence of French philosopher Michel Foucault was much more apparent, although Said never fully embraced Foucault’s denial of an objective reality. As Zachary Lockman notes in Contending Visions of the Middle East: The History and Politics of Orientalism, “Said’s embrace of Foucault was always partial and ambivalent.” Together with Gramsci, Said also admired the Marxist cultural critic Raymond Williams and later openly broke, as Lockman notes, with “Foucault’s ‘overblown’ conception of power,” insisting “on the possibility of a more just future society. . . .”

Said’s appreciation for the importance of the concept of cultural hegemony surfaced again in his later critique of the way the corporate media promulgated Islamophobia with his book Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World (1981).

How do these theoretical concepts translate into practice? A BDS campaign in Portland, Oregon, led by a coalition of religious, social justice, peace, and secular left groups known as Occupation-Free Portland, provides some insights.

The objective of the campaign was to persuade the City Council to divest from any corporations involved in the Israeli occupation. It was the Palestine solidarity community’s first attempt at a political BDS campaign aimed at a representative, democratic institution; all previous campaigns having been economic—that is, aimed at convincing retailers to deshelve Israeli products. Tellingly, this political BDS campaign was the first to garner public opposition from the local Zionist Lobby, particularly the Jewish Federation of Greater Portland, which had previously ignored economic boycott campaigns.

The campaign’s first major victory came when the city’s Human Rights Commission (HRC) voted unanimously to endorse the call for the city to divest any holdings in four corporations—Caterpillar, G4S, Hewlett-Packard and Motorola Solutions—due to their complicity in the Israeli occupation. The endorsement was itself a signal that the dominant narrative was changing inasmuch as this voluntary, unpaid civil society institution understood completely that Palestinian human rights were being violated, especially after witnessing the massacre of Gaza in 2014. As the former chair of the HRC put it to me when I asked if the HRC would consider our resolution “controversial,”she responded, “Not anymore.”

The HRC endorsement led to a campaign of intimidation launched by the Community Relations Council of the Jewish Federation, also a civil society institution. The Federation issued a statement condemning the HRC which was signed by leaders of the Democratic Party establishment—the mayor, a leading mayoral candidate, and a member of Congress—along with the president of Portland State University. Negative media coverage also ensued. In effect, the Federation revealed the principal pillars of its civil society support—the media, the academy, and the Democratic Party—all of whom supported the bipartisan hegemonic narrative that denies Palestinian rights and upholds Israel as a strategic U.S. ally.

It’s worth dwelling on this campaign of intimidation because it proved to be a pivotal moment in the campaign and because it shows that cultural hegemony also has a component of coercion and in effect acts as an adjunct to state repression. In addition to issuing its statement, the Federation also appears to have organized an email and telephone campaign that included physical threats made against members of the HRC. As the chair of the HRC acknowledged in an email to other members, “the threats of bodily harm are not to be taken lightly.” One of the strengths of the HRC as an institution derived from its role as a voluntary, unpaid advisory commission made up of people with an interest in human rights. It was also made up predominantly of people of color, in part because of its role in civilian oversight of a racist police force. Because HRC members were unpaid, the intimidation campaign could not use the coercive method of firing someone and depriving them of income. If that option had been available, it surely would have been used.

The head of the Federation’s Community Relations Council also threatened the chair of the HRC with the promise that “the shit is about to hit the fan.”He warned that negative media coverage was about to appear in the Willamette Week, a local “alternative”newspaper. Sure enough a disparaging article soon appeared in that publication, dismissing the HRC as an “obscure Commission.”

Communal pressure also appeared to have caused the two Jewish members of the HRC to reconsider their vote, with both claiming they didn’t know what they were voting on when they voted to approve the divestment resolution. The intimidation campaign succeeded in pressuring the HRC to schedule a second community hearing where it would consider a motion to rescind its vote.

Several factors came into play here. The fact that physical threats had been used led the mayor to back off from his promise to attend the second hearing. His community liaison director told us that death threats had been made. The mayor clearly did not want to be associated with those tactics, and so did not show up at the second hearing, where his mere presence might have swayed the HRC’s position. Instead the issue would be decided solely on the basis of persuasion rather than coercion. A huge community turnout in support of the resolution and the failure of the opposition to even address the facts presented regarding corporate complicity in the Israeli occupation led the HRC to refuse to reconsider its original vote. The HRC chair cited the fact that they had not heard any evidence rebutting our argument of corporate complicity in Israel’s illegal occupation.

As Gramsci might have said, the people put forward their own counter hegemonic narrative and won. Progressive civil society groups and organizations, particularly from the faith community, from traditional civil rights groups, from Jewish Voice for Peace, and from the Palestinian-American community, used moral leadership “good sense” and defeated the dominant hegemonic narrative that attempted to deny Palestinian human rights.

What Said might have said about the differing roles and narratives emanating from civil society also bears examination. I believe Said would have “taken an inventory” and noted that a white male used abusive hegemonic language against an African-American woman, the chair of the HRC, when he threatened that “the shit was going to hit the fan.” Said might have pointed out that one of the Jewish members of the HRC also told the chair that she needed to be “educated,” as if she was a member of an inferior culture that couldn’t understand the “superior”culture, the wellsprings of which Said described so effectively in Orientalism. And finally he probably would have noted that the sole Native American member of the HRC remarked that she could not vote otherwise than to uphold Palestinian rights considering “what happened to my ancestors.” This woman had taken her own inventory and knew that what happened to Native Americans was the same ethnic cleansing that the Palestinians experienced under Zionist colonization.

In a sense the Federation had unwittingly mirrored the racism Israel exhibits toward Palestinians. Our campaign enabled people to get a glimpse of the Palestinian experience. When the dominant culture is a culture of white and male supremacy, it’s inevitable that the dominant hegemonic narrative will reflect these characteristics, as the Federation did with its intimidation tactics.

In the end, the opposition had so discredited itself that subsequently one of the members of Congress who signed the Federation statement appeared to disown it when she told a visiting delegation that she “really hadn’t read what it said.”

The clash between the Federation and the HRC resulted in another crack in civil society’s role of upholding the dominant paradigm; namely, the role played by the media. In addition to the negative coverage in the Willamette Week, the editor/publisher of that publication also submitted a public records request asking for the HRC’s internal email correspondence, apparently assuming that it could base another disparaging article on the email it obtained. In the event, however, no subsequent article on the HRC was ever published. Curious, I submitted my own request for the exact same records, thinking that the Willamette Week might have decided to drop its coverage because the records revealed information damaging to the Federation. Sure enough references to “threats of bodily harm”appeared in the emails. The newspaper would have been obligated to report that or risk its credibility. Its subsequent coverage of the OFP campaign proved to be much more even-handed.

Similarly, a campaign organized by Students United for Palestinian Equal Rights (SUPER) at Portland State University helped undermine and isolate the role played by the PSU president in backing the Federation. SUPER successfully brought a divestment resolution to the Student Senate, which backed it by an overwhelming vote of 20-2. Thus, the students offered a convincing and dramatic counter narrative to the university administration.

The OFP campaign in effect heralded the emergence of a people’s counter hegemonic narrative that enlisted its own support within civil society. That support included not just institutions like the Human Rights Commission but also the city’s Socially Responsible Investments Committee and the religious community, including Christian, Muslim, and Jewish groups, and students. Traditional secular left groups were also involved and helped provide leadership but lacked the mass base and energy generated by the human rights, student, and faith communities.

It became obvious that a sea change had occurred in civil society, especially after the Socially Responsible Investments Committee (SRIC) voted 4-2 to recommend that the City divest from Caterpillar due to its human rights violations in Israel/Palestine. When that occurred, the city’s leading newspaper, The Oregonian, finally took note of the changing narrative and editorialized against the SRIC recommendation, claiming lamely that Caterpillar “just makes tractors.”

Despite these successes, however, the campaign ultimately failed to break the dominant Progressive Except Palestine (PEP) paradigm. The City Council voted to stop investing in all corporate securities. One councilor said the issue took up too much of his time, while another suggested that citizens’ objections to corporate investments was likely to be never ending and it was probably best to get out of all corporate investments. One OFP supporter remarked that when confronted with the argument that Palestinian Lives Matter, the Council responded by saying All Lives Matter. The third and deciding vote on the five-member council came from a councilor who was prepared to accept the SRIC report, including its recommendation to stop investing in Caterpillar, and joined with the other two Councilors to ensure the City would divest from corporate bonds. However, not one of the Councilors ever said anything openly against Caterpillar’s role in the Occupation; in effect, keeping the PEP paradigm intact. One councilor even suggested that she could not say anything publicly about Palestine because she had so many Jewish friends, as if “identity politics”was the sole determiner of her political positions.

OFP activists were themselves divided on how to assess the end results. Some considered it a partial victory because objectively the city of Portland did stop investing in Caterpillar. Moreover, the Palestine solidarity movement demonstrated that it was a political force that could not be ignored or disrespected. We succeeded not only in marshaling community pressure but also in allying with other progressive forces, particularly the Prison Divestment Campaign, which was targeting Wells Fargo. At the April City Council hearing, an alliance of environmental, Palestine, and Prison Divestment activists came together to demand adoption of the SRIC’s final report. Palestine had never before been such a prominent focus of City Council hearings.

All of this was true, and yet not one word from the City Councilors about Palestine. In the end it proved too difficult for them politically to risk stating open support for Palestinian rights. Ironically the only political nod the campaign ever received was when one councilor chastised the Federation for suggesting that Jewish Voice for Peace was made up of “fringe Jews” and “extremists.” But our campaign was not about Jewish support for Palestine. It was about Palestine itself.

Here are my takeaways from what a Gramscian-Said analysis reveals:

—civil society is increasingly divided over Israel/Palestine. The cultural hegemony exercised by pro-Israel institutions can be successfully challenged with a Palestinian counter-narrative that one day will itself become hegemonic.

—pro-Israel civil society institutions will attempt to use coercion when it can, knowing that its ability to persuade or to establish hegemony by consent no longer works due to increased awareness and knowledge of the injustice done to Palestinians.

—Palestine solidarity activists need to exercise moral leadership, showing that the Palestinian struggle is a liberation struggle and therefore a moral movement. By exercising moral leadership, it can unite broad sections of civil society, especially in the faith and human rights communities, to challenge, neutralize or even win over those sections of civil society most likely to support the dominant hegemonic narrative—that is, the Democratic Party leadership, the academy, and the media.

—By directly challenging the principal proponents of the Israeli narrative, the opposition can be counted on to expose its own “inventory”of racism, sexism, arrogance, authoritarianism, and colonialism.

—Palestine solidarity activists must “take their own inventory,”understanding that they, too, are influenced by the dominant hegemonic culture. Suggestions of downplaying Palestine in intersectional alliances because Palestine is considered controversial are an example of internalizing the dominant narrative and succumbing to it rather than challenging it. Palestine solidarity activists must guard against a tendency toward national chauvinism, “condescending savior” paternalism, prioritizing domestic issues over international issues (a kind of left-wing American Firstism), and Palestine isolationism.

–Finally, Gramsci’s concept of a “war of position” provides further guidance for the BDS movement. By “war of position,” Gramsci acknowledged that in advanced capitalist countries with well-established constitutionalism, the forces for change face a protracted struggle in which a principal objective is to establish a people’s counter-hegemonic narrative to the dominant neoliberal narrative of the ruling class. This struggle demands engaging with all sectors of civil society and winning them to the people’s narrative.

As the German activist Rudi Duetscke, a student of Gramsci’s, put it, we must begin the “long march through the institutions” of civil society. And the longest march begins with a single step.

– Rod Such is a former editor for World Book and Encarta encyclopedias. He lives in Portland, Oregon, and is active with the Occupation-Free Portland campaign.