By Benay Blend

Several years ago, at an event in Albuquerque, New Mexico, a Palestinian activist visiting from California told me about his torture during detainment in Israeli prisons. The marks on his back resembled that of the enslaved man Gordon, whose iconic photograph “The Scourged Back” survives today as a testament to the brutality of slavery.

He also told me that he received a political education and learned to speak several languages while in prison. Indeed, there is a long history of prisoner solidarity as well as internal political education that spans prisons across the world.

To honor Palestinian Prisoners’ Day on April 17, the Masar Badil, Palestinian Alternative Revolutionary Path Movement, calls upon its organizations, along with Palestinian people in the diaspora, to organize demonstrations in support of the Palestinian prisoners’ movements in occupation and US jails.

After Minister of Defense Itamar Ben Gvir’s attempts to pass highly restrictive laws, the prisoners’ movement enacted a series of escalating tactics designed to overturn Ben Gvir’s actions. According to Munther Khalaf Mufleh, a Palestinian writer and journalist as well as spokesperson for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), the movement soon announced an open hunger strike along with a list of demands.

What made their recent victory possible was the emergence of a Higher National Committee, representing all Palestinian factions, under the slogan of “national unity and true partnership.” As Mufleh notes:

“All of these achievements would not have been realized if it had not been for the will of our Palestinian people and their valiant resistance that was present with us and always pushes us to greater action, but this achievement is a step on the road of a thousand miles to our goal of freedom and liberation.”

The use of administrative detention is well-known for intimidating resistance leaders as well as members of their families. For example, activist Iyad Burnat, from the village of Bil’in, explains that “this has been my life since childhood and this is how my children have grown up. We do not know how to give up.” Despite knowing that his two sons are now being held in detention without a trial, Burnat continues to fight for his community.

According to Randa Musa, wife of the prisoner Khadar Anan, who is now on his sixth hunger strike, occupation prisons inflict systematic collective punishment against the prisoners, including isolation, medical neglect, denial of family visits and education, and efforts to rescind the achievements gained through previous collective strikes.

Indeed, unity is a theme woven throughout Palestinian resistance, especially among prisoners in their struggle. Mai Masri’s film 3000 Nights (2015) documents the experiences of a group of Palestinian women in Israel’s Ramla prison. “The 1980s was a time when Palestinian women prisoners from PFLP [the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine], Fatah etc., fought the authorities for every single thing – even a pencil,” Masri said.

Layal, the central character, is not a member of the resistance when she is mistakenly arrested. In prison, she is drawn into her cell mates’ communal life, especially after she gives birth to a baby boy. Her life is changed, politically and personally, as she gains strength through her solidarity with the other women prisoners.

Similarly, during Argentina’s seven years of military rule (1976-1983), known as the Processo, there was a period of state-sponsored repression and violence that resulted in approximately 30,000 deaths and disappearances. In The Little School (1998), a secret prison ironically named for its former status, activist/poet Alicia Partnoy creates what she calls a “discourse of solidarity” (“Textual Strategies to Resist Disappearance and the Mothers of the Plaza de Maya,” Florida Atlantic Comparative Studies Journal 12, 2010-2011, p. 5), testimonials of her cell mates that come together as a collective story of the disappeared.

In prison, Partnoy transformed the poetry that she wrote for her daughter to fit any prisoner’s child. Writing for specific occasions not only helped her survive, she found that it also helped to lift the spirit of her friends. In this way, she took on the suffering of other captive mothers, a communal effort much like the cell mates who help raise Layal’s boy.

On March 14, 1954, the film Salt of the Earth premiered in New York City. Based on the Empire Zinc Strike of 1951-52 in New Mexico, it tells the story of striking miners, mostly Mexican Americans, in their quest for economic, racial and gender justice. Much like the Palestinian prisoners’ movement, it celebrates the ability of collective action to create a better world.

Echoing Palestinian connection to the land, Esperanza, wife of a leader of the strike, explains that the miners also wants the world to know that “our roots go deep in this place, deeper than the pines, deeper than the mine shaft” that contributes to the destruction of the land.

After an injunction is placed on the strikers, their wives take over the picket line because they are not members of the union. When the women are arrested by the police, Esperanza takes her baby with her. As the baby grows hungry, they begin chanting slogans for the officers to release them or bring essentials to feed the baby.

To this day the iconic cry “We want the formula” is repeated when women want their voices to be heard. The film also used members of the community as actors in the film, some of them miners who had participated in the strike. For years in my New Mexico history classes, at least one student had stories to tell of relatives who had acted in the movie.

By exploring these other stories—from New Mexico, Argentina and beyond–Palestinians are placed within a broader narrative of transnational solidarity and resistance.

After her release from prison in September 2021, Khalida Jarrar used her position as a researcher at Birzeit University to use similar approach that focuses on Palestinian women prisoners. By means of a comparative study, she looks at colonial experiences in Ireland, Algeria, and the Khiam prison in South Lebanon. For Jarrar, the prisoner’s movement is a collective struggle that must include the women.

Reiterating Jarrar’s transnational approach, Samidoun makes clear that “Palestinian women prisoners are not alone; they struggle alongside fellow women political prisoners in the Philippines, Turkey, India, Egypt and around the world.”

“Palestinian women have always been at the center of the liberation movement,” Samidoun explains. Participants in “all aspects of [the] struggle,” women have “led within the prisoners’ movement, organizing hunger strikes and standing on the front lines of struggle even behind bars.”

On February 21, 2023, Palestinian prisoners called for collective action in support of an escalating program of struggle. According to Samidoun, the Higher National Emergency Committee of the Palestinian Prisoners’ Movement issued a statement announcing a series of actions ending with an open hunger strike. Entitled “Freedom or Martyrdom,” the Committee called on “every capable prisoner of all factions” to engage in the strike to be brought together under “unified demands and unified leadership,” because “unity,” by both prisoners and their supporters, is the “main guarantor” of success.

On March 23, 2023, the prisoners declared their victory in the “Volcano of Freedom or Martyrdom” campaign. Due to their resistance, the Zionist prison service rescinded the new restrictions, after which the prisoners suspended the hunger strike scheduled to begin on March 23.

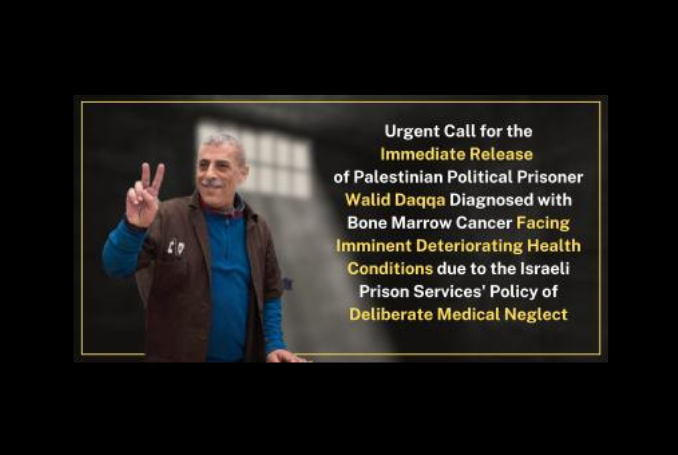

Nevertheless, Walid Daqqah, a Palestinian writer and one of the longest-held political prisoners, remains in prison after being diagnosed with myelofibrosis, a rare form of bone marrow cancer that requires a marrow transplant. According to a statement from his family, he is currently being held at Barzilai Medical Center, after having part of his right lung removed.

He remains one of many Palestinian prisoners who are in dire need of urgent medical attention. As Prisoners’ Day approaches, his family asks for his immediate release to receive treatment in a hospital where he can get the necessary care. They are also demanding the formation of a medical team composed of his family, prisoners’ institutions, and human rights organizations to visit Walid so that they can transmit information about his condition to the world.

In a message Samidoun received from prisoners of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) in occupation jails, there was also a call to support an international campaign of solidarity with the leader Ahmad Sa’adat, Abu Ghassan.

In their view, Sa’dat’s “revolutionary spirit” reminds the world that “Palestine is not an imagined geography, it is part of this world and still represents the destination of revolutionaries everywhere.” Indeed, the statement concludes that “the cause of the prisoners transcends borders, geographies, walls, and parallel time. It is a revolution confronting injustice in which our prisoners unite with revolutionary prisoners around the world in the dungeons of oppression and persecution,” important words to remember on Palestine Prisoners Day.

– Benay Blend earned her doctorate in American Studies from the University of New Mexico. Her scholarly works include Douglas Vakoch and Sam Mickey, Eds. (2017), “’Neither Homeland Nor Exile are Words’: ‘Situated Knowledge’ in the Works of Palestinian and Native American Writers”. She contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.