By Sam Bahour

These last few days, as they do every year, weigh heavy on every Palestinian’s heart. For me, and my family, the heaviness is also personal.

Every Palestinian carries around two hearts. One is similar to that which all others carry; it keeps us alive, active, working, loving, moving, singing, playing, and hopeful that tomorrow will bring a better day. The second is very difficult to explain; it is the one that carries within it dark and heavy memories of our existence. Every Palestinian carries this dark heart, albeit the number of chambers in each varies; for far too many, new chambers are added daily, yet others are calcified but fully preserved.

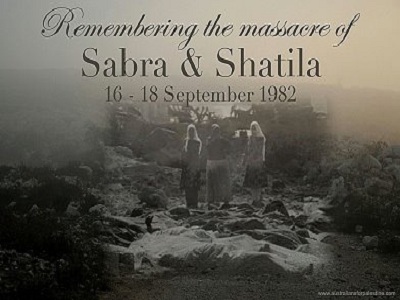

These days bring to the forefront one of those chambers present in all of our black hearts. This week, 33 years ago, in full coordination with the Israeli military which had invaded South Lebanon a few months prior, a group of “Christian” Phalangist fundamentalists, entered two Palestinian refugee camps, Sabra and Shatila, and slaughtered over 3,000 Palestinian civilians. Most were murdered assassination style, using hatchets, striking mostly to the head. Several victims were beheaded. Children, women, men, young and old, no one was safe. September 16 and 17 were the days when the bulk of the cold-blooded rampage took place. On September 18th journalists finally made their way into the camp and the horrific scenes became known to all. Later, in 1983, the Israeli government appointed the Kahan Commission to investigate the incident. The Commission deemed Israel indirectly responsible, and Ariel Sharon, then Israel’s Defense Minister, personally responsible, forcing him to resign, deeming him unfit to serve as Defense Minister. Sharon later went on to become a popular Israeli Prime Minister.

During the massacre, I was in Youngstown, Ohio. Like Palestinian communities worldwide, we were glued to the TV screens in total shock. It was too painful to just sit and endlessly watch the unfolding event any longer. The news footage of the humanitarian organization workers, wearing masks to protect themselves from the overwhelming stench of death, picked the bodies, one by one, off the piles on which they lie dead. As the bodies were lowered into the hastily dug mass graves, it felt that we too were being lowered in this resting place, with every descending body, over and over.

Watching all this from the Arab-American Community Center in Youngstown, we decided to act. We started to plan an emergency mock funeral that would place empty symbolic coffins on car rooftops and drive through the city in procession, ending symbolically at one of the local cemeteries. We were determined that our city must be aware of the war crime that had just took place against the Palestinian people thousands of miles away. The Palestinian Americans in our community felt an obligation to not only denounce the killings but to explain that the dead are Palestinian refugees, kicked out of their homes in what today is Israel, and refused their right to return home by Israel, the US’s strategic ally. Several in our community were born and raised in Lebanon’s refugee camps; some of the murdered were personally known to them. This made the event even more traumatic, because if they were not in Youngstown they could have been a victim of this crime.

The mock funeral procession was a huge success. My grandmother wanted to attend, but my father asked her to stay home because she was not feeling well. The entire community participated. Dozens of Americans joined in solidarity. The clergy of the city spoke out. We felt we did our part. The mock funeral was over. We all went home.

As I reached our house on Roosevelt Drive, my sister and I were frantically called to immediately go to my grandmother Badia’s house, three houses away, on Northview Blvd. We had no idea why the rush. We ran to her house. She was laying on the carpet, immobile, quiet, but awake. She had third degree burns on her entire body. An ambulance was called. My dad was called to come and arrived before the ambulance. He went into shock and has never been the same person since that day. Grandma was rushed to St. Elizabeth Hospital less than two miles away, which is the best medical center in the region. She was then to be air lifted to the nationally renowned Akron Hospital Burn Unit, a specialized facility. Bad weather did not permit the ambulance helicopter to be used, so in an Intensive Care Ambulance, she was transported to Akron, 45 minutes away. She fought for her life for a little more than a week before succumbing to her wounds on September 29, 1982. We buried her two days later, it was her 60th birthday.

The funeral wake was difficult. The casket remained closed. As tradition calls for, a Koran reading was playing in the background as friends and family paid their last respects. Then, half way through the evening, in a standing room only hall, my heartbroken father walked to the tape recorder. He pressed stop and removed the Koran cassette and replaced it with one he had brought with him; we had prepared it together the night before. When he pressed play, Mahmoud Darwish’s poem, “My Mother”, performed by Lebanese musician Marcel Khalife, rang out in the utter silence. Several of the elders in the room leaped up toward the tape recorder, thinking my father had made a mistake. He asked them to sit back down. He wanted this song played. The tears which fell at that moment washed my grandmother’s soul, yet again, along with each and every soul of the victims of Sabra and Shatila.

How was she burned? Grandma Badia, we learned afterwards, was in the initial stages, or so we thought, of Parkinson’s disease. It turns out the disease was more advanced than doctors could diagnose. She needed constant care. The massacre taking place in Sabra and Shatila was too much for us all. In the heat of the moment everyone left to the mock funeral procession, leaving grandma home alone in the hope that she would get some rest. The accident was caused by an oven fire while she was cooking dinner for all of us who were out demonstrating, at least this is what the fire department investigation revealed. I’ll never accept that. My grandmother was one more victim of Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon and the subsequent massacre in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps.

Two events in my younger years transfixed me on dedicating my entire life to the Palestinians’ struggle for freedom, this event and the First Intifada. I want to mourn but I can’t anymore because all the other chambers in my dark heart fiercely compete. Do I mourn my grandmother or the nearly 3,500 murdered in Sabra and Shatila? Or do I mourn all 20,000 Palestinians and Lebanese killed in that war? Or do I recall Qana, and if so, which massacre there, the first or second? While Qana beats on the walls of its chamber, Deir Yassin and Kufr Qassem can be heard screaming in the background. In between the screaming there are the smaller “events,” the bombing of buildings, the assassinations, the unreported natural deaths of refugees in exile and internally displaced Palestinians in Israel, and political prisoners languishing in detention. Then, more recent memory yells out — Gaza 2000, Gaza 2002, Gaza 2006, Gaza 2008/9, Gaza 2012, and then Gaza 2014 deafens me. When my senses return, the one-and-a-half year-old Palestinian infant, Ali Saad Dawabsheh, who was burned to death last month in the West Bank village of Duma, near Nablus, by Israeli settlers who firebombed his home while the family was asleep haunts me. Ali’s father died a few days later from his burn wounds and his mother died a few weeks after her husband from hers. Ali’s now orphan brother will survive, like so many before him, damaged for life, but alive. The list is never-ending!

Yes, there are days when the heavy heart crams the other heart into a corner of our chest, making it difficult to take a deep breath, at times bringing painful thumps to the forefront. But I refuse to despair. I refuse to be defined by this conflict. I do not want to mold my existence into days of commemorations of exile, massacres, death and destruction. I refuse to live in the past, but I also refuse to forget the past. I remember in order to respect, to learn, to understand my present, and to define how I will chart my future. For those looking in from the outside it will be hard to comprehend; how a person can live a schizophrenic life but not be infected with the disorder itself. How, in the same day, a conscious mind and beating heart can make the case that a policy of slow ethnic cleansing is being undertaken against them, while the same mind and heart, the normal one, can live a life of hope that is totally convinced that tomorrow will witness better times.

This is our predicament as Palestinians, we have no alternative but to struggle with our internal turmoil as we attempt to maintain our sanity and raise the next generation to understand that both of their hearts will compete for their chest space too, regrettably.

– Sam Bahour is a Palestinian American living in his ancestral home in Al-Bireh, Palestine, eating from the same fig, almond and olive trees that his father and Grandmother Badia ate from before leaving Palestine. He contributed this article to PalestineChronicle.com. Visit his blog: www.epalestine.com.