By Ramzy Baroud

Editor’s Note: Today, Tuesday, December 8, marks the 33rd anniversary of the First Palestinian Intifada. On this day, in 1987, the uprising broke out throughout occupied Palestine, generating massive solidarity for the Palestinian people across the Middle East and the world.

The uprising lasted for nearly seven years and came to an end as a result of numerous pressures and political manipulations by various parties. Systematic Israeli violence, which led to the killing and wounding of thousands, and lack of meaningful political support from the PLO and Arab governments, pushed the Palestinian people to eventually abandon what was then one of the greatest acts of sustainable popular rebellion in modern history.

Below are excerpts from Ramzy Baroud’s book ‘My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story’, where he describes the start of the Intifada in his refugee camp in Gaza.

Where Were You When the Intifada Started?

It’s not easy to isolate specific dates and events that spark popular revolutions. Genuine collective rebellion cannot be rationalized through a coherent line of logic that elapses time and space; it’s rather a culmination of experiences that unite the individual to the collective, their conscious and subconscious, their relationships with their immediate surroundings and with that which is not so immediate, all colliding and exploding into a fury that cannot be suppressed.

When on December 8, 1987, thousands took to the streets of Jabaliya refugee camp, the Gaza Strip’s largest and poorest camp, the timing and the location of their uprising was most fitting, most rational, most necessary. And yet it unleashed one of the most chaotic and painful periods in Gaza’s history.

I was a first-year student at the Khaled ibn al-Walid High School for Boys when the Intifada started. Being a student at that specific high school was a rite of passage. It was in Khaled ibn al-Walid where Palestinian army volunteers were trained before the war of 1967. The school served as a hub for nationalist gatherings, fiery speeches and occasional visits by high-ranking Egyptian and PLO officials. Some of its teachers became nationally regarded Palestinian leaders. Some of its students became the most celebrated Palestinian activists, prisoners and martyrs.

Khaled ibn al-Walid required a uniform consisting of a pair of blue jeans and a blue button-down shirt. Several days before the summer break came to a close, my mother took me and my brothers to the local market, where I giddily picked out a new pair of jeans and a shirt. Although my fashion sense was painfully lacking, I joyously embraced my new and reputable role as a pupil in the legendary institution. By then, I was known as the ‘poet’. My nationalist poetry and prose armed my father with ample opportunities to invite intellectuals and various activists to our house for many performances, which my father found exhilarating and I, embarrassing to no end. I would be summoned in with my thick notebook to the sitting room, often full of cigarette smoke, laughter and overflowing Palestinian coffee. At my father’s behest, I would recite to admiring visitors, who would, convincingly or not, inundate my father and I with praise for raising such an erudite son.

But my short-lived happy outlook on life was not felt throughout my home, or among most Palestinians in the Gaza Strip.

My grandfather had just passed away. He was an old man. But his demise in a decaying refugee house, not far from ours, was particularly demoralizing, for my grandfather never gave up on the idea that someday he would lead his family back to his distant and now absent village of Beit Daras. Israel had long-since erased the entire village, but it lived, in its entirety, in my grandfather’s memory, its homes, its earthen pathways, its orchards, people and mosques. Following the Nakba, my grandfather was involved in life in the refugee camp in a nominal capacity that allowed him to survive and care for his family, but his heart was truly left in Beit Daras. On his deathbed, the old man asked to be buried in his orchard on the outskirts of his beloved village. Of course, none of his wishes, to return in life or in death were ever fulfilled. Instead, he was buried by the tiny grave of my older brother Anwar. Soon after, Zeinab followed her husband and was also buried in the ever-crowded cemetery. Their deaths left my father with much to ponder and regret. For once, he squarely blamed himself for the tumultuous relationship that he had with his parents, his mother in particular.

But my father’s woes were not totally sentimental. My sister, Suma, was advancing through medical school with expenses that consumed much of the man’s humble resources. Anwar and Thaer graduated from high school and were ready for their next move, both aspiring to study at a West Bank university. My father understood that meeting the new demands for higher education would require more substantial, and risky business deals in Israel, again.

But then the Intifada started, on one hand articulating and venting Mohammed’s own grievances, rejection and disdain of the occupation and the humiliating legacy it espoused, and on the other, making his regular trips to Israel most arduous, and eventually, altogether impossible. Indeed, the Intifada was a strange dichotomy for many, as it expressed the outrage of a whole nation, while also articulating a sense of collective hope, and more, inexorably inviting untold harm, both physical and psychological.

Why Revolution

The eruption of the Intifada cannot be faultlessly explained by one individual, for it meant different things to different people. It was a popular and spontaneous retort to the injustice and the humiliation felt on a daily basis by Palestinians living in the occupied territories. But, although to a lesser degree, it was an expression of frustration that the Palestinian struggle was becoming a marginal issue on the agendas of Arab governments. As Arab governments were widely entertaining prospects of a settlement with Israel, pressures were mounting on the now sidelined, Tunis headquartered PLO to revise its political priorities. In Lebanon, the presence of Palestinians looked bleak, as refugee camps were under intense attacks from various militias and by the Israeli air force. One single Israeli raid on Ein al-Hilweh refugee camp, on September 5, 1987, killed as many as 50 refugees.

In the occupied territories, the picture appeared equally grim. Before the Intifada, acts of resistance were present but sporadic. Much of the clashes in the Gaza Strip took place between students and Israeli troops, who used tear gas and mostly rubber bullets to disperse protesters. Many students were affiliated or were supporters of leading PLO factions. Fatah was becoming the most visible faction in Palestinian schools and universities through the rise of the Fatah youth movement, known as “Shabiba”. The Islamic movement was divided between the Islamic Compound, which later became Hamas, and the Islamic Jihad, a highly secretive and greatly daring militant grouping.

It is as if Gaza had lost every trace of fear. Gazans became most daring in a time when Israel expected them to be most pacified and subservient. And when they rebelled, as has always been the case, they took everyone by surprise.

The Soldiers Are Coming

On Tuesday, December 8, 1987, an Israeli truck driver drove his large vehicle into the opposite lane of traffic and hit several Palestinian vehicles, which were hauling some of Gaza’s laborers in Israel, killing four and seriously injuring eight.

The four young laborers killed that day were cousins of my father and descendants of Beit Daras. Israel maintained that the killings were an accident, while Palestinians believed that it was another revenge attack. When the bodies of the four men were lowered into the ground, emotions ran high. The grisly scene was the last straw, and the death of the laborers suddenly represented the grievances of a whole generation.

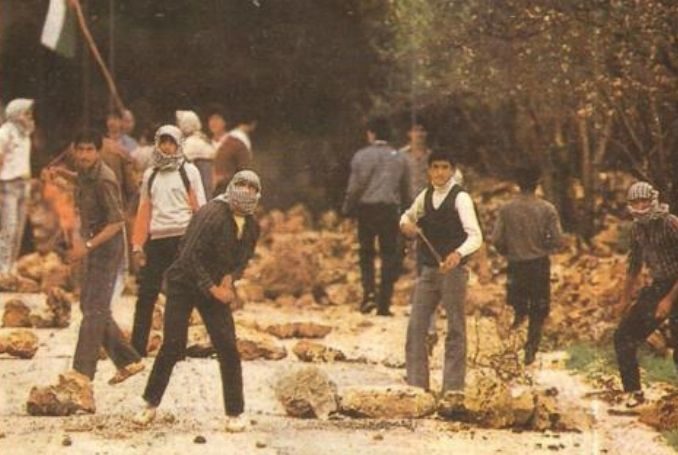

Hundreds of young men gathered in Jabaliya, near an army camp surrounded with barbed wire and began hurling stones at the soldiers. The distance between the young men and the soldiers was far enough that the act seemed largely benign and symbolic, but when the Israeli army opened fire, all representation evaporated. Riots engulfed the entire camp, and the sound of Israeli gunfire was heard throughout adjacent areas, as screaming ambulances began hauling Jabaliya’s casualties to Gaza City hospitals. On that evening, Gaza’s relative calm, interrupted by an occasional encounter between a Palestinian fighter and Israeli troops turned into absolute mayhem. The moment long anticipated finally happened.

By then, a few months into the new school year, my lone blue jeans and shirt looked old and scruffy, despite my incessant attempts at maintaining the looks suitable for a student at Khaled ibn al-Walid. Regardless, my enthusiasm remained strong.

It was Wednesday, December 9, 1987. Following our morning exercise, the school principal ordered us into class, but we, for once, refused to comply. Flyers distributed by student political groups urged all students to march in protest of the killing of the four laborers and the violence that followed in Jabaliya. I knew that today was no ordinary day, and had already resolved to confront the occupying forces, disobeying my father’s clear instructions to come home if I sensed trouble. The teachers tried to force us into class; they even began whipping students’ feet with long sticks, almost herding us back to our classrooms. We had no specific plan, but we knew that dutifully sitting at our desks that day was entirely out of the question.

All it took was one daring student to stand up in the center of the schoolyard and start waving a Palestinian flag. The students began chanting, praising the martyrs of Jabaliya: “Rest assured, oh martyrs, for we shall carry on with the struggle,” “mothers of our beloved martyrs, do not weep, for we are all your children,” and so on. Within a few minutes, the entire school was marching, followed by nearby schools, and within an hour, thousands of refugees throughout the Nuseirat refugee camp were moving in one large, unprecedented mass.

Many such protests took place in the past in our refugee camp, but the speed at which thousands gathered, the intensity of the chants, the tears of the many women who marched alongside, once the protest reached the camp’s central market, all promised that today was not like any other. Some youth began burning tires, atop a small hill in the center of the camp, signaling for others to join in, but also sending a message of protest to Israeli soldiers at the military encampment, stationed strategically between Buraij and Nuseirat refugee camps.

Israeli soldiers quickly poured into the camp, some on foot, others in large military vehicles and small military jeeps. The battle was to commence. Women, children and elders were urged to leave before the arrival of the troops. Many young men also retreated. I was terrified and exhilarated. I was no longer a middle school student, but a student at Khaled ibn al-Walid, and could no longer justify my flight. I picked up a stone, but stood still. Others ran away, but some ran towards the soldiers, with their rocks and flags. The soldiers drew nearer. They looked frightening and foreign. But when the kids ran in the direction of the soldiers and rocks began flying everywhere, I was no longer anxious. I belonged there. I ran into the inferno with my schoolbag in one hand, and a stone in the other. “Allahu Akhbar!”, I cried, and I threw my stone. I hit no target, for the rock fell just a short distance ahead of me, but I felt liberated, no longer a negligible refugee standing in a long line before an UNRWA feeding center for a dry falafel sandwich.

Engulfed by my own rebellious feelings, I picked up another stone, and a third. I moved forward, even as bullets flew, even as my friends began falling all around me. I could finally articulate who I was, and for the first time on my own terms. My name was Ramzy, and I was the son of Mohammed, a freedom fighter from Nuseirat, who was driven out of his village of Beit Daras, and the grandson of a peasant who died with a broken heart and was buried beside the grave of my brother, a little boy who died because there was no medicine in the refugee camp’s UN clinic. My mother was Zarefah, a refugee who couldn’t spell her name, whose illiteracy was compensated by a heart overflowing with love for her children and her people, a woman who had the patience of a prophet. I was a free boy; in fact, I was a free man.

As I finally made my way home, with my shirt torn, my knuckles bloodied and my face stained with tears from the teargas, I saw my mother, running in a panic, barefoot and still in her pajamas, calling out my name and the names of my brothers. She spotted me and began weeping.

– Ramzy Baroud is a journalist and the Editor of The Palestine Chronicle. He is the author of five books. His latest is “These Chains Will Be Broken: Palestinian Stories of Struggle and Defiance in Israeli Prisons” (Clarity Press). Dr. Baroud is a Non-resident Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Islam and Global Affairs (CIGA) and also at the Afro-Middle East Center (AMEC). His website is www.ramzybaroud.net

– Ramzy Baroud is a journalist and the Editor of The Palestine Chronicle. He is the author of six books. His latest book, co-edited with Ilan Pappé, is “Our Vision for Liberation: Engaged Palestinian Leaders and Intellectuals Speak out”. Dr. Baroud is a Non-resident Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Islam and Global Affairs (CIGA). His website is www.ramzybaroud.net