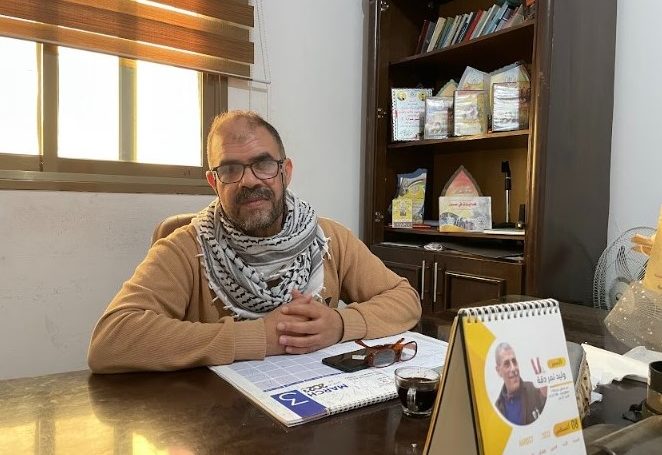

Hussein Al-Zrai’i, 43, was imprisoned for 19 years after being charged with belonging to the Palestinian Resistance.

During his imprisonment, he carried out three hunger strikes: in 2004, which lasted for 18 days, in 2012, for 28 days, and in 2017, for 42 days.

Al-Zrai’i describes his detention as the “most challenging” stage of his life and the hunger strike as one of the “most challenging” experiences he endured in prison.

Dignity in Hunger

“The hunger strike was the only option we have to live in dignity in the face of the inhumane practices of the Israeli authorities,” Hussein told The Palestine Chronicle.

Before resorting to hunger strikes, Palestinian prisoners used to address the Israeli prison administration to improve their living conditions, to demand cooking utensils, ventilation in their cells, and the right to family visits.

“Although we were asking for basic human rights, the Israeli occupation was deliberately rejecting our demands, in complete disregard of international law,” Al-Zrai’i said.

On April 17, 2004, Al-Zrai’i embarked on a hunger strike along with other Palestinian prisoners. They had two main requests, one, the release of those detained in solitary confinement and, two to allow prisoners to have family visits.

“The Israeli prison administration implemented several punitive measures to break our spirit and push us to end our hunger strike, including toasting bread in front of us, so that the smell would spread throughout the ward,” Al-Zrai’i said.

Palestinian prisoners did not surrender.

“We launched the second strike on April 17, 2012. It was known as ‘the Gaza strike’.”

It was named ‘the Gaza Strike’ because it was launched to demand the Israeli government lift its ban on family visits to Gaza detainees, who had been denied visits for years.

“During my 19-year detention, I have never seen my parents,” Al-Zrai’i told us.

Al-Zrai’i explained that the prisoners also asked for an improvement in their living conditions.

Israeli prison authorities implement policies to deliberately harass Palestinian prisoners, depriving them of their fundamental rights, enshrined in international law.

“In 2017, we launched a hunger strike to protest the harsh measures implemented by the Israeli authorities,” Al-Zrai’i said.

Over 1,000 Palestinian prisoners took part in the 2017 hunger strike, which involved all Palestinian Resistance parties. It was triggered by the Israeli authorities’ decision to shut down the ventilation system in the prisoners’ cells and prohibit family visits.

“In 2017, I fainted on the 38th day of the strike. I hit my head on the floor pretty badly, everyone in the prison could hear that. The other prisoners repeatedly called the jailers, but they only arrived twenty minutes later. I had already woken up.”

“The officer took me to the clinic, where an Israeli nurse refused to treat me. He put fruit in front of me and said that he would only treat me if I started eating again,” Al-Zrai’i said.

Being on a hunger strike puts a strain on prisoners’ bodies: they experience fainting and joint and bone pain, among other complications.

Some prisoners suffer from convulsions, nerve tension, and high temperatures even years after the hunger strike is over.

“Throughout the strike, Israeli authorities frequently moved us from one prison to another, which exhausted us physically,” Al-Zrai’i said.

Though seven years have passed since Al-Zrai’i’s last hunger strike, he is still suffering from medical complications, a lack of vitamins, and low iron levels.

Al-Zrai’i’s story is just one of many similar experiences faced by Palestinian prisoners in Israeli prisons.

Last Resort

Tayseer Al-Mardini, 53, spent a total of 19 years in Israeli prisons, and he underwent several hunger strikes.

He was sentenced to life in prison before being released in 2011 as part of the Shalit prisoner exchange deal.

Throughout his imprisonment, Al-Mardini embarked on five different hunger strikes, ranging from 6 to 24 days.

Tayseer explained that strikes were only undertaken as a last resort.

In the 2004 strike, Al-Mardini was one of the leaders of the hunger strike, as he embarked on in 1989.

“They isolated me and other strike leaders in separate cells to break prisoners’ determination and will. “We were fighting for basic rights such as sleeping on a pillow, having a radio, and cooking our own meals,” Tayseer told the Palestine Chronicle.

The living condition in which Tayseer lived was inhuman; it was a one-meter cell with a pit latrine and without beds, mattresses, or blankets.

“The IPS used negotiation and threatened us to break the strike without any results for prisoners.”

“As a hunger strike leader, I used to hide my pain in front of the IPS because they used to mention our suffering in front of other prisoners to break down their determination,” he said.

Although the strikes achieved some positive results, Tayseer knew they were “temporary victories” as the IPS always breaks its promises for prisoners.

It’s not all about the health complications that led to Khader Adnand’s death but it takes a psychological toll on prisoners like feeling helpless and humiliated.

Adnan died in an Israeli prison, on May 2, following 87 days of uninterrupted hunger strike.

“Prison administration used psychological methods to break the strikes, such as distributing leaflets about the dangers of the strike and isolating prisoners in cells.”

Hunger strikes are the only way for Palestinian prisoners to fight for their rights, even though they are extremely painful and have long-term health consequences, he explained.

The current situation of hunger strike prisoners remains a source of pain for Tayseer due to his painful experiences in the past.

– Mahmoud Mushtaha is a Gaza-based freelance Journalist and translator. WANN contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.