By Dr. Samah Jabr

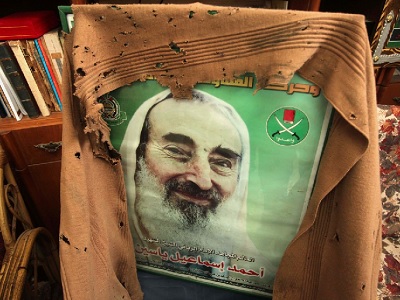

Neither the fact nor the brutal manner of Sheikh Ahmed Yassin’s cruel assassination on 22 March 2004 was surprising, nor was Israel’s indifference to the severe human cost paid by other Palestinians who happened to be around the sheikh at the time; nine other people were killed in the attack.

Sheikh Yassin was not the first and will not be the last Palestinian leader to be killed in the struggle for Palestinian rights. Israel has assassinated many Palestinians and non-Palestinians — intellectuals, writers and artists from across the political and ideological spectrum — who led the fight against its military occupation of Palestine. Every democratically-elected Israeli prime minister has assassinated Palestinian leaders in the occupied territories, refugee camps and throughout the Diaspora. What I find astonishing, though, is the stunningly accurate way in which Sheikh Yassin’s assassination in particular serves as a metaphor to reveal the nature of the Palestine-Israel conflict.

The image of a US-made Apache attack helicopter launching three sophisticated missiles to kill a quadriplegic, near-deaf, 69 year-old man as he left his local mosque in his wheelchair after the dawn prayer, exemplifies what is taking place in occupied Palestine. The sheikh was also made almost blind by the “moderate physical pressure” applied by Israeli prison interrogators. Israel’s predisposition is to resort to the logic of power to smother the Palestinians’ power of logic as they struggle for a free and decent life in the land of their birth.

As a boy in 1948, Sheikh Yassin was driven by Zionist militias from his village, Al-Jura, near Askalan. For the rest of his life, he lived as a refugee in a small, modest home in a poor neighbourhood in the Gaza Strip. Even though for all of his adult life he was a captive of his wheelchair, Sheikh Yassin had a creative mind and a big heart. A brave, influential and daring speaker, he was known for his wisdom, balanced assessment and steadfast faith. Contrary to what the manipulative Western media likes to claim, he did not struggle to exterminate the Jews and create an Islamic empire. In fact, he made a clear distinction between the Jews per se and the Zionists occupying his land. He did, however, advocate armed resistance to liberate occupied Palestine and end Israel’s daily killing and oppression of the Palestinians.

Some of us agreed and some of us disagreed with the vision, opinions and strategies of Sheikh Yassin and his organisation, Hamas, but we all knew that he loved Palestine and so we loved him, and we united with him in this love. Those who are aware of the politics of the occupied land know that Ahmed Yassin was a fair and responsible leader. Indeed, many Israelis refer to him, and to Ismael Abu-Shanab, the high-ranking Hamas leader who was assassinated last year, as the “soft-liners” in the Islamic Resistance Movement. The two men knew when to say yes and when to say no to armed resistance; they cooperated with the Fatah-controlled Palestinian Authority and offered more than one hudna — truce — that the Israeli government violated.

The Israelis could easily have arrested Sheikh Yassin if they thought that removing him from the public domain would be beneficial; after all, they had done so before. They could have taken him to court and tried him if they really believed that they could prove him to be guilty of terrorism. Instead they chose extrajudicial murder to get rid of him, even though they knew very well that this could damage Israel’s security severely, and jeopardise the political options for a resolution of the conflict.

This should not be a surprise to anyone; it is no secret that the Zionist project has always used terror to achieve its objectives. This is what Zionists have declared and practiced since the first international Zionist congress in 1897. They use terror to kill Palestinians and ethnically-cleanse their land, to threaten Arab nations and blackmail the international community. They killed Sheikh Yassin to call for more blood and spread fear and intimidation in Palestinian hearts. “I, too, like Hitler, believe in the power of the blood idea,” wrote Chaim Nachman Bialik, Israel’s much-admired Zionist poet, in his 1934 work “The Present Hour”.

Israel’s killing machines work in synchrony with its media. The day after Ahmed Yassin was assassinated, international media broadcast footage of a 14-year-old Palestinian boy from Nablus who arrived at the Hawwara checkpoint wearing an explosive vest. “He came seeking help from Israeli soldiers,” said an army spokeswoman, “and he was well cared for. But we need to find out those evil people behind him.”

The point of the report was to show the world how horrible the Palestinians are and that they truly deserve death, and thus serve as damage control for the images of the smashed wheel chair over the large bloodstain — all that was left of Yassin — in the previous day’s news reports. Only Al-Jazeera reported that the boy’s “mental capacity… is very low,” and quoted another boy from Nablus, also presented as a would-be suicide bomber, who reportedly told his family that the Israelis “told me to do this or else they would kill me.”

Even the international community’s weak official disapproval of Sheikh Yassin’s assassination was countered by yet another US veto of a Security Council resolution condemning the latest Israeli violation of international law.

Today, there is a feeling of dread and depression among Palestinians. While we have different opinions about what has occurred and various expectations of what will ensue, the one thing we all realise is that Israel is seeking a bloody war, not peace, with the Palestinians.

Our task now is to develop strategies corresponding to this realisation. Despite our mourning, anger and apprehension, giving up is certainly not an option.

In their attacks on Palestinians over the decades, the Israelis have put many of us in wheelchairs — literally and metaphorically — and sought to cripple and restrain us. Despite his violent death, however, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, a man bound to his own wheelchair, gave us a model of resoluteness, sincerity and gallantry. We hold our heads high for being the children and grandchildren of the man who chose his path, and lived and died according to his principles. The teacher is gone, but his lessons are eternal.

– Samah Jabr is a Jerusalemite psychiatrist and psychotherapist who cares about the wellbeing of her community – beyond issues of mental illness. (This article was originally published in MEMO)