By Benay Blend

For Palestinians, the term sumud translates as steadfastness, including a strong attachment to the land, even in exile, but also a mental state that leads to determined action.

Defining sumud as inherently optimistic, Laleh Khalili explains that it refers to the nation’s perseverance in dire times. Unlike the kind of hero worship peculiar to Western culture, the word signifies collective resistance by holding communities together (Heroes and Martyrs, 2007, p.101).

“A narrative of sumud recognizes and valorizes the teller’s (and by extension the nation’s) agency, ability and capacity in dire circumstances,” she writes, “but it differs from the heroic narrative in that it does not aspire to super-human audacity,” but instead values women’s work of “holding the family together and providing sustenance and protection for the family” (p. 101).

As a collective trait, sumud has served the Palestinian resistance and contributes to their refusal to leave the homeland, even in the wake of increased collective punishment by the Israeli military since October 7th. In the diaspora, Palestinians are steadfast in maintaining their culture, community, and identity in the face of assimilation, discrimination, as well as cooptation of their national foods in foreign countries and the homeland, too.

Food is at the core of history, identity, and, more than ever, life, as Palestinians in Gaza are facing starvation due to the Israeli blockade and settlers who are blocking aid trucks from entering the Strip. Because Palestinian food is a cultural symbol that ties the people to the soil, appropriation of Palestinian cuisine is also a tool of the Israeli occupation. By claiming that their dishes belong to Israeli national identity rather than the Palestinians who have long lived on the land, the entity denies Palestinians their indigeneity. Accordingly, food carries with it a political intent.

Moreover, nearly 200 sites of cultural importance in Gaza have been destroyed or damaged since October 7th, including libraries, religious sites, and places of historical importance, thus making the preservation of non-material culture more important now than ever. South Africa, which brought the charge of genocide against Israel to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), asked that the ICJ act swiftly “to protect against further, severe and irreparable harm to the rights including the heritage of the Palestinian people under the genocide convention.”

Euro-Med Rights Monitor added that Israel’s destruction of educational institutions and cultural objects is a form of genocide. Fadel Alatel, an archaeologist in Gaza and part of the Heritage for Peace network, told Aljazeera that heritage sites in Gaza are clearly marked, yet Israel’s destruction of them continues. Despite the trauma of the present, Alatel conveyed his faith that “this will end. Even if they attempt to destroy our past, we will build back Gaza’s future.”

Alatel expresses the legendary sumud associated with Palestinians, even more so here because memory work relies on the past, which for Palestinians is part of the present in the form of daily Nakbas that have yet to have firm closure.

In their favor, social media has played a role by enabling Palestinians in the homeland to connect with their families abroad, and by helping all those who love Palestine to spread information that counters mainstream news. The Facebook group Mama’s Palestinian Kitchen (MPK) functions in several ways to provide an outlet far beyond the mere sharing of recipes, although that, too, is important. Established by activist Abbas Hamideh, MPK offers a space to honor Palestinian cuisine by posting photos and recipes passed down from previous generations, thereby encouraging others to create similar dishes in their homes.

Some members share how they are comforted in these times by aromas that remind them of their childhood (“In remembering my childhood, one of my aunts used to make a sweet called mabroosheh, that she would bring to our family gatherings. This was one of my favourites growing up but, unfortunately, my aunt lost the recipe years back. Finally found it and made it for the first time today”), others express a reluctance to enjoy their food at a time when there is so little to eat in Gaza (“Perfecting my khubz while feeling guilty I have flour to make it, a kitchen and stove to cook it in, and limbs to hold the spatula”).

Most cultures employ traditional cuisine to maintain the bonds of their communities. In Hisashi Kashiwai’s The Kamogawa Food Detectives (2024), a retired detective and his daughter run a restaurant in Kyoto that attracts a particular clientele. Through clever investigations, the father-daughter duo recreate definitive dishes from a person’s past, thereby allowing the client to movement forward into a better future.

On the one hand, he Kamogawas are interested in protecting their cuisine from Western influence, so in this way they are like Palestinians who wish to preserve authentic food. On the other, the latter cannot so easily escape their past if repeated Nakbas define their future.

Long before October 7th, Zionists in Israel and abroad began claiming Palestinian cuisine as their own, thus employing another way to erase the Palestinian presence from their land. As Nylah Burton notes, food theft is a tool of the Israeli occupation, thereby erasing Palestinian history on the land while putting forth the claim that these dishes are part of Israeli culture rather than the people of Palestine and groups that share its border.

In another move to sever Palestinians from the land, Israel banned the gathering of za’taar in 1977, under the guise of conservation but really to hinder the Indigenous practice of harvesting the herb for its medicinal benefits as well as flavoring traditional cuisine. Because of it grows everywhere with very little tending, za’taar, like the olive trees, has long been a symbol of rootedness and sumud for Palestinians.

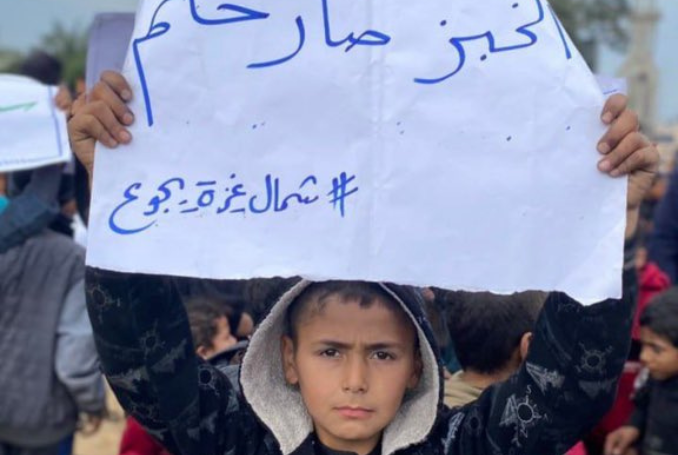

As Ramadan approaches, The UN agency for Palestine refugees, UNRWA, announced that the last time aid was delivered to the Gaza Strip was over a month ago. To add to their problems, Israel has bombed the aid trucks going into Gaza with food. In the wake of this human-caused disaster, Palestinians are grinding animal feed to serve in place of flour for making bread.

In “Of Families, Mills, and Gardens,” activist and writer Alison Glick shares her recent communication with a friend in Gaza. “The occupation seeks to uproot life from the land, including homes and crops, and deliberately removes history by targeting antiquities and all archaeological buildings,” H explains, but continues that, despite the trauma, many wish to stay.

In the end, he says: “It is true that there are many people who prefer to flee and search for a safe place outside the Gaza Strip, but this is not the case for the majority of people for many reasons. It is not easy to start life again away from a homeland that you love,” attesting to the resilience and sumud associated with Palestinians.

Last year on May 1, 2023, the Palestine Chronicle Staff followed in photographs an event in Khan Younis, Palestine, that commemorated the Nakba with art, bread, coffee, and, significantly, hope. That year the Palestinian community in the southern Gaza Strip celebrated the artwork, poetry, and embroidery that was done by a “young generation that has grown up stateless or in exile,” young people who understand that hope is as fundamental to their life as is mourning.

Food also played a role in the festival in the form of Palestinian bread, known as shrak, and freshly brewed coffee, served according to “Palestinian Bedouin traditions.” This year, too, there is hope that now as then, this second Nakba will serve as “a foundation for a new beginning, one of redemption, resistance, unity, and hope.”

“Indeed, the Nakba is an all-encompassing Palestinian story of the past, present but also the future,” claims activist/journalist Ramzy Baroud. “It is not only a story of victimization, but also of Palestinian sumud – steadfastness – and resistance.”

Written last year, these words still have significance, perhaps more so since Western media seldom conveys Palestinians as controllers of their fate. “For Palestinians, the Nakba is not a single date,” Baroud concludes. “It is the whole story, the conclusion of which will be written, this time, by the Palestinians themselves.”

– Benay Blend earned her doctorate in American Studies from the University of New Mexico. Her scholarly works include Douglas Vakoch and Sam Mickey, Eds. (2017), “’Neither Homeland Nor Exile are Words’: ‘Situated Knowledge’ in the Works of Palestinian and Native American Writers”. She contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.