By Ida Audeh

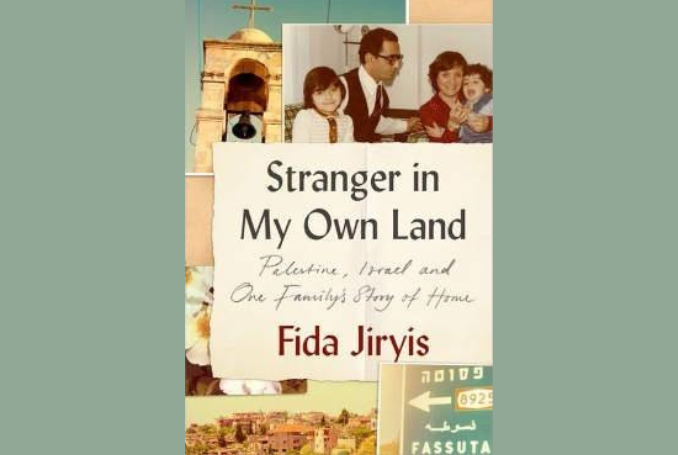

(Stranger in My Own Land: Palestine, Israel and One Family’s Story of Home. By Fida Jiryis, Hurst, 2023)

Stranger in My Own Land tells the story of Palestine since 1948 through two generations of one family.

The author’s maternal and paternal families were among the minority who remained in Israel after the Nakba, and they soon realized that the new triumphalist Jewish state desired to strip them of any hope of shaping their own destinies as Palestinians. The author’s parents made the difficult and unpopular decision to emigrate in 1970, leaving for Lebanon to work in a PLO-affiliated research institute.

Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982 and its aftermath forced the shattered family to move to Cyprus to start over yet again. Twelve years later, the family was among very few with roots in what became Israel who were allowed to return to their villages, on the coattails of the Oslo Accords. The narrative ends in 2022, with the author still struggling to find her way in Palestine.

This tour de force—part family history, part memoir—was ten years in the making, copiously researched through published sources and extensive family interviews. The author clearly writes for an audience with little familiarity with Palestinian history.

She deftly gives as much historical context as readers need to understand events and policies (for example, the Zionist plans to depopulate Palestine and the laws governing land appropriation) and then switches back to her family members and friends to depict the lived experience. The result is a comprehensive portrayal of living as members of an unwanted population in a settler colonial structure that desires their permanent marginalization.

Author Fida Jiryis is the daughter of Sabri Jiryis, whose 1966 book, The Arabs in Israel, used Israeli sources to document the network of laws, military orders and courts that Israel used to suppress Palestinian citizens. (Palestinians in Israel lived under military rule between 1948 and the end of 1966, a system that Israel would resurrect in the territories it occupied in June 1967.)

The first third of the book shows the human cost of such a system as well as the resilience of the indigenous minority. The author relates the early stages of political organizing by her father and his friends in the 1950s and the effort to bring international attention to their plight. (They sent dozens of letters to the U.N. through various routes to ensure that at least one eluded the military censors and reached its destination. The strategy worked.)

In the Arab world, the 1967 defeat was a staggering blow, but for Palestinians in Israel, it allowed them to visit parts of Palestine previously controlled by Jordan and Egypt that had been off-limits. This provided an opportunity to meet other Palestinians, from whom they’d been separated for decades. Palestinian refugees live with memories of the homes they were expelled from, but Jiryis makes us wonder about the experience of Palestinians who remained, or who live within range of depopulated villages, and recall a time when they hummed with life and were interconnected.

In the last third of the book, the 22-year-old Jiryis and her family return to Fassouta, their village in the north, and the story is firmly hers: she explores what it means to reclaim a home that had always seemed the stuff of fantasy. We see it through her eyes as she struggles to find a job (most require proof of military service), to rent an apartment, even to shop in a mall without harassment.

When she finally gets a well-paying job, she has to endure frosty coworkers who ignore her and who support bombing a Palestinian area—and no one, not even a friendly coworker, finds the call for genocide objectionable.

She realizes that she will always be reminded of her status when she interacts with Israelis: “It was not possible to live for even one day without being reminded that we were us and they were them—and that we may never be accepted as equal to them.” If living in Israel is difficult, living in Ramallah (where Jiryis relocated, hoping to more fully reconnect with her heritage) is even more so—she lives under military rule, her movement constrained, her water rationed, the apartheid wall ever present.

This memoir delves deeply into the experience of a nation that has had to find ways to survive a military juggernaut determined to erase it—in historic Palestine, in Lebanon, and even further afield. (The book includes photos of more than four dozen Palestinian diplomats and political figures assassinated by Israel around the world.)

Beautifully written by a Palestinian woman who is eager to find her home in a state that has cost her family so much, this book eloquently conveys the urgency of transforming the toxic status quo into conditions that allow everyone to thrive as equals.

This review was originally published in the June/July 2023 Washington Report on Middle East Affairs and was contributed by the author to The Palestine Chronicle.

– Ida Audeh is a contributing editor of the Washington Report. She contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.