By Benay Blend

When asked why the Front refused to engage in peace talks, Kanafani retorted that such talks resulted in “capitulation,” a form of “conversation between the sort and the neck” that ended in “surrendering”.

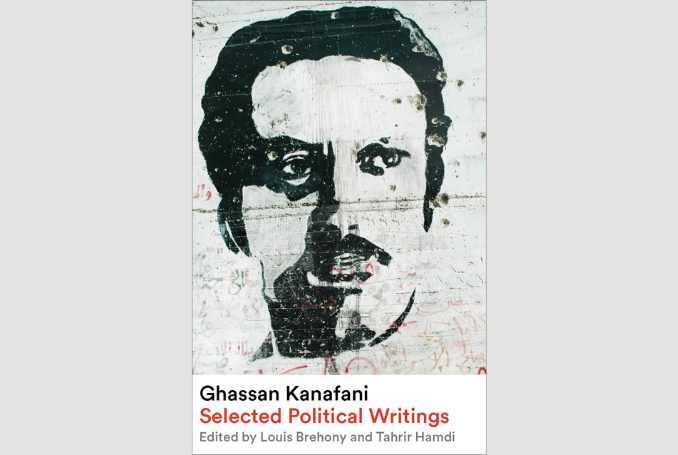

Edited by Louis Brehony and Tahrir Hamdi, Ghassan Kanafani: Selected Political Writings (2024) brings together Kanafani’s views on history, politics, national liberation, and the media translated into English for the first time. For Kanafani, resistance was the essence of everything he wrote as well as the life he led as a revolutionary thinker who fought for Palestinian liberation with his pen.

No stranger to displacement, Kanafani’s family was ethnically cleansed from Palestine during the Nakba in 1948, thereafter to live as refugees in various makeshift camps, much like the displaced in Gaza do today (p.1). Inspired by these experiences, Kanafani would spend his life writing stories, political articles, analyses, and manifestos, many linked to publications put out by organizations to which he belonged, including the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and its precursor the Arab Nationalist Movement (ANM) (p.2).

The book is organized according to prominent themes in the writer’s work—Kanafani and the media, building the Marxist-Leninist Front, and Arab nationalism and socialism, to name a few. Each chapter features commentary by leading writers, an arrangement that fits seamlessly into Kanafani’s style, as his work benefitted from collective input generated by other members of al-Hadaf, the PFLP newspaper that he helped develop.

Kanafani was assassinated on July 8, 1972, by the “Israeli” Mossad, for his revolutionary writing and his role in the PFLP. His work lives on in Palestine’s current struggle and among those who are in solidarity with the movement.

“Kanafani was an outstanding and sometimes prophetic visionary,” the editors write, “whose works are as relevant today as they have ever been” (p.4).

On Thanksgiving Day 2024, a holiday that Nick Estes, co-founder of the Indigenous resistance group The Red Nation and a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe, explains marks the Pequot massacre by members of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, it’s important to note that Kanafani was an internationalist who saw Palestine as “an integrated human symbol” (p. 27) that reflects the misery of colonized people around the world.

As Khaled Barakat notes, the PFLP’s Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine (1969) reveals the Front’s connection with anti-colonial and revolutionary movements around the world, and this relationship has continued to this day. Like his work with al-Hadaf, Kanafani participated in developing the document, but it was a collective piece (pp. 94, 95).

“The Palestinian and Arab liberation movement does not move in a vacuum,” Kanafani wrote. “It lives and fights in the midst of specific world circumstances that affect and react with it, and all this will determine our fate. The internation ground on which national liberation movements move has always been, and will remain, a basic factor in determining people’s destinies” (p. 111).

At that time, Kanafani looked to the liberation struggle in Vietnam, the “new situation” (p. 111) in Cuba and national liberation movements in Asia, Africa and Latin America. He saw these struggles as “the only way to create a camp that is capable of facing and triumphing over the imperialist camp” (p. 112).

If Kanafani was writing today, he would have included the Indigenous peoples of the Americas in this list, for there is a reciprocal recognition between the Indigenous here and in Palestine of their common struggles.

At Standing Rock in 2016 and 2017, there were Palestinian flags flying in solidarity with that struggle. According to Estes, that sign of mutuality “harken[ed] back to that international solidarity with movements of the Global South, and specifically our Palestinian relatives.” Whether its “settler colonialism in Israel — or, in Palestine,” he concludes, the latter is “really an extension of settler colonialism in North America.”

“This history … is a continuing history of genocide, of settler colonialism and, basically, the founding myths of this country,” says Estes, much like the origin stories around the state of “Israel.” Moreover, he explains that the current genocide on Palestinian life has roots in the belief that colonial society acted in pre-emptive “self-defense” when they annihilated the Native people.

Otherwise, story goes, the Indigenous would have attacked the colonists, an excuse that the media repeats by reiterating Israel’s right to self-defense. “But the colonized are never granted the authority of self-defense or the right not to be annihilated,” Estes says, in a statement that mirrors claims by Kanafani.

The section entitled “Kanafani and the Media,” appropriately introduced by Palestine Chronicle’s managing editor Romana Rubeo, features the martyr’s conversation with Richard Carleton of the Australian Broadcasting Company (ABC). As Rubeo explains, Kanafani “showed himself to be aware of the ongoing war of narratives” (p. 194), thus he chose very carefully the words to frame the Palestinian struggle for freedom, much like Estes does today.

Kanafani’s responses are still applicable today, as Rubeo contends. In answer to Carleton’s claim that the Jordanian war was “fruitless,” Kanafani replied, “We achieved that our people could never be defeated” (p. 194), a claim that remains true to this day.

When asked why the Front refused to engage in peace talks, Kanafani retorted that such talks resulted in “capitulation,” a form of “conversation between the sort and the neck” that ended in “surrendering” (p. 197).

Kanafani then elaborated on what he considered the essence of resistance: “To us,” he concluded, “to liberate our country, to have dignity, to have respect, to have mere human rights is something as essential as life itself” (p. 198). In that one sentence, he explained what would become the rationale for October 7th.

To this day, writes Ramzy Baroud, founder of Palestine Chronicle, Western powers and their liberal followers continue to talk about bringing peace to the Middle East, but they usually neglect to mention justice.

“As far as Palestinians are concerned,” Baroud contends, “there can only be one acceptable ‘deal’, a deal that is predicated on the full implementation of international law, including the Palestinian people’s right of return and right to self-determination.”

Similarly, the next section, introduced by Ibrahim Aoude, provides lessons for developing a counter-narrative to the Zionist colonial project. The controversy centered on a book entitled Children of Israel, a text which was destined for use in Danish public schools. Written by an “Israeli” writer, the book included what Edward Said has termed Orientalism, a combination of “racism, settler colonialism, and arrogance” (p. 202) used to justify the superiority of the colonizer over the Other.

Letters back and forth between the PFLP and the publisher put the latter on defense, and it was an exchange that resulted in withdrawal of the books. The stakes for the PFLP were high, Aoude explains, as Zionist forces controlled the media as they still do today (p. 203).

This collection of Kanafani’s writing provides invaluable material for political education. As repression increases against diasporic Palestinians and their supporters, its important to know this history. Only then can a solid defense be built against those who are intent on silencing organizing around Palestine forever.

Father of Ahed Tamimi from the village of Nabi Salih in the “Israeli”-occupied West Bank, Bassem Tamimi spoke here in Albuquerque several years ago. When a member of the audience what he does for self-care, Tamimi answered: “I continue to resist.” Resistance is the essence of his being, as it was for Kanafani and his fellow Palestinians many years before.

– Benay Blend earned her doctorate in American Studies from the University of New Mexico. Her scholarly works include Douglas Vakoch and Sam Mickey, Eds. (2017), “’Neither Homeland Nor Exile are Words’: ‘Situated Knowledge’ in the Works of Palestinian and Native American Writers”. She contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.

I believe you mean to say ‘sword’ instead of ‘sort’, as in ‘conversation between the sword and the neck’.