By Haidar Eid

(Kanafani, Ghassan . Men in the Sun. (Trans. Hilary Kilpatrick). London: Heinemann, 1978. —.

All That’s Left to You. (Trans. May Jayyusi and Jeremy Reed). Austin: Univ. of Texas Press, 1990.)

The necessity of reading Palestinian literature, especially at this point in time, emanates from the importance of writing a Palestinian Narrative. Most Palestinian literature is what Barbara Harlow would call “Resistance Literature.”

Our familiarity and knowledge of this kind of literature, in a post-apartheid and post-cold war world, has unfortunately been determined by what the market offers us. Our familiarity with the poetry of Mahmoud Darwish, Samih El-Qasim, Tawfik Zayyad and the novels of Emil Habibi, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, Ibrahim Nasrallah and Ghassan Kanafani—to mention but a few—is extremely poor, to say the least. If these great writers get read, it is only in Departments of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies. Edward Said is undoubtedly lucky enough to write in English and be published in the States.

But I am also thinking of ways to counter Israeli Hasbara. Take for example what ex-deputy director-general for cultural affairs of the Israeli Foreign Ministry, Arye Mekel, had to say:

“We will send well-known novelists and writers overseas, theater companies, exhibits… This way you show Israel’s prettier face, so we are not thought of purely in the context of war.”

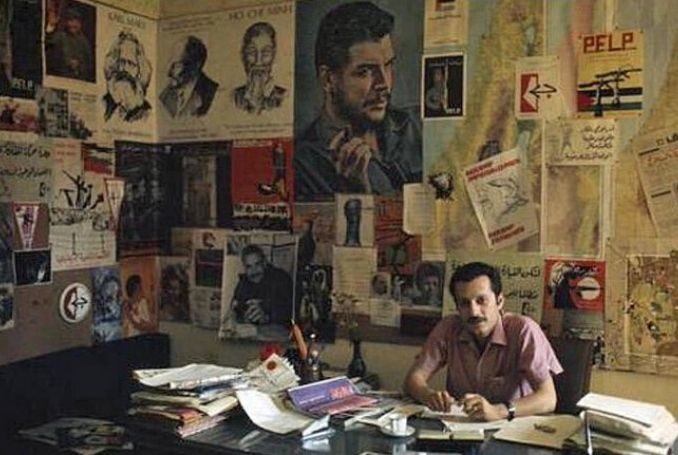

Let me offer a re-reading of two novels of one of the most popular Palestinian writers of Arabic literature, Ghassan Kanafani within the context of the latest developments in (post)- Oslo Palestine.

Ghassan Kanafani’s stories of the struggle of (wo)men to free themselves from certain inhuman forms of exploitation, oppression, and persecution are undoubtedly related to the ideas, values and feelings by which colonized (wo)men experience their society and their existential, political, and historical situation.

An understanding of Kanafani’s novels requires an understanding of both the past of the oppressed Palestinians and their present more deeply: an understanding that contributes to their liberation, and to human liberation in general. It is not difficult for any reader of these two novels (Kanafani’s early novels) to notice a gradual, conscious, deliberate movement towards a clear dynamic reality: a new reality that makes us see what we have never seen before, that moves us into a new order of perception and experience altogether. In other words, both novels have a great artistic influence that emerges from a confrontation with reality, rather than an attempt to escape from it.

Complicated themes and questions recur throughout these novels: exile, marginalization, death and history. Such questions are, indeed, related to the role of Kanafani as a self-conscious committed writer revealing the weakness of some Palestinians (who stand for the colonized people in general) in preferring the search for material security to the fight to regain their land (Men in the Sun).

The responsibility of the Palestinian leadership in allowing Palestinians to suffocate in the marginal world of refugee camps is amazingly foreseen in this novel. However, the world of the different Palestinian characters is a composite of a poetic and organic relationship with the land. Being separated from the land, and seeking individualistic solutions, leads the men in the sun to an undignified, tragic death. What the novel explores, then, is the dialectical relationship between the inward and the outward realities of the Palestinian refugee.

The world of All That Remains, on the other hand, is a world of socio-political paralysis that needs to open up new possibilities for a better future. This requires a journey towards historical consciousness: a fact that takes the 1948 war as the emerging Centre and the frozen Palestinian image. In this novel, historical consciousness is reached through individual and collective transformation; and real, meaningful time of freedom is reached through action.

Of course, in order to reach historical consciousness, one must get rid of false consciousness. The novel is, therefore, left without an end because it is about beginnings rather than endings, i.e. about a non-ending dialectical process. Hence with the optimistic, open–albeit violent–ending of All That Remains, and the call for social revolution in Men in The Sun, one concludes that, contrary to Francis Fukuyama’s theorization, history can never be closed.

Hamid, the hero of All that Remains, is an oppressed Palestinian who is searching for his land, history and identity, which are restored through his struggle to regain his land. The true center of All That Remains is not only Hamid, but the real conditions of war and occupation which are responsible for the loss of the land/Yafa/Palestine.

We readers are directed toward an examination of the conditions of persecution and war– including the ethnic cleansing of Palestine by Zionist militias– responsible for that disaster; it is Hamid’s behavior itself that we are invited to scrutinize. These are events that affect Hamid’s/Palestinian’s character, and the result is the revolutionary action at the end of the novel in 1965, i.e. the emergence of the contemporary Palestinian Revolution. With Kanafani one realizes that a new world is possible, even inevitable, in spite of Caesar’s deal of the century!

But why the need for a rereading of Kanafani?

The inconsistency of the rising Oslo intelligentsia is to be found on the scale of that of the petty-bourgeoisie. This is why it has shown itself, in the end, to be conservative, sometimes even reactionary where the main problems are concerned, as other traditionally Arab liberal intellectuals, and why it does not tolerate any thought for critically conscious observations.

Not surprisingly, those who do not approve of, for example, Edward Said’s sharp critique of the Oslo Accords are the principal beneficiaries. What these intellectuals need to redress is the very nature of the serious problems confronting us in the 21st C in Palestine. As we expect the “fat cats” to be against any form of critical consciousness, we, however, expect the intelligentsia to enhance it. Alternative programs, such as those offered by the likes of Kanafani and Said, have been working as a mirror reflecting the ‘Other’ Palestine, the real face that we have been repressing. Hence the intimidation, anger, and accusation of ‘idealism’ and ‘sentimentality!’

The program of the new rising, Osloized intellectuals tend to obscure class-relations and what legitimates them, i.e., the exploitative relations of production that are still dominant, by moralizing bourgeoisie nationalism over class. In a way, rereading Kanafani, similar to that of Edward Said’s, shows us how and why the current hegemonic ‘intellectual’ structure, with its structure of domination, does not represent a radical change in terms of relations with the Israeli occupier, but rather a modification of it.

Political consciousness must begin with a rejection of the conditions imposed by the Israeli occupation on the majority of Palestinians and even more crucially, a rejection of the crumbs that are offered as a reward for good behavior to a select minority!

Hence the necessity for re-readings of Kanafani.

– Haidar Eid is an Associate Professor in the Department of English Literature at the Al-Aqsa University, in the Gaza Strip. He contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.

– Haidar Eid is an Associate Professor in the Department of English Literature at the Al-Aqsa University, in the Gaza Strip. He is a research associate at the Center for Asian Studies in Africa at the University of Pretoria. He contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.