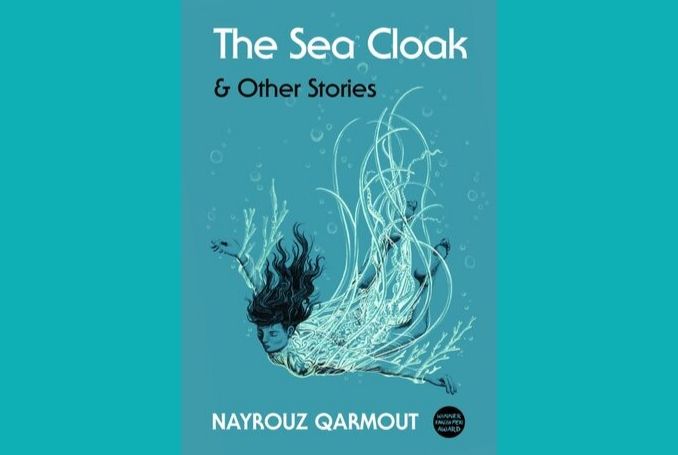

(Excerpts from The Sea Clock, by Nayrouz Qarmout. Comma Press. Manchester, 2019.)

Their feet were too small for the task. They lengthened their strides as the road opened up before them, breaking into a run, panting, filling their tiny lungs with the excitement of being out of school. Tattered shoes pounded the tarmac, fringed by the frayed edges of school trousers. Old schoolbags bounced up and down their backs. On either side of them lay the rubble of destroyed buildings, like the damage caused by a storm that had torn through the little city overnight.

The sky was getting lighter as the sun inched upwards.

A donkey-pulled cart waited for them at the end of the street. Jumping into it, the two boys were greeted by their older brother’s usual complaints: ‘I told you a million times, you need to get here sooner. I am tired of always waiting for you. We’re losing valuable time here. ‘They could hardly see the older brother’s face under his baseball cap; his skin was so dark from endless days spent in the burning sun that only the whites of his eyes could be seen under its brim.

‘Giddy-up!’ he cried, with a crack of his whip, and the cart jolted into motion.

The donkey was no show pony; there was nothing graceful about the way it trotted down the road. Every pothole bounced its passengers into the air, and the sound of its metal shoes scraping the tarmac was painful. But it was a hard worker, and patient, as were the three boys it lugged around all day. The cart took up more of the road than was allowed, often jutting out into the pavement. Together, the donkey, cart and boys didn’t abide by the city’s traffic laws; they constituted a rogue body, following its own rules, only caring that it reached its destination, with all components still intact.

‘Get off the road!’ shouted one driver.‘Are you mad?’

‘The road is for cars,’ added a policeman, loitering on a street corner.

The fifteen-year-old at the reins ignored them, pulling down his cap till it covered his eyes; ‘Giddy-up, Donkey,’ he repeated, along with those encouraging clicking sounds donkeys appreciate if you want them to obey you. Twenty minutes later they were there.

The children threw down their bags and disembarked into what might have looked like a warren of sand dunes rising and falling ahead of them, had it not been made of fractured concrete and twisted metal.

Adham, the youngest of the three boys, quickly scrambled to the top of the nearest heap, and began picking out small rocks to pass to his brother, Asaad, who took up position a few paces below him on the side of the heap. Instead of handing them down to him, however, Adham had learned to throw them with such precision and care that they always landed gently and perfectly in Asaad’s hands. The boy at the top of the heap had an eye like a telescope; he could not only find the right sized stones instantly, but could judge throwing distances down to the last millimeter. He analyzed everything from his vantage point, the way a surveyor measures a circle of land from every position.

It was getting hotter. Bulldozers and stone-crushers were appearing all around them; huge machines whose first job was to clear a space on the ground from which to work. One set of vehicles was having to start the day by clearing a building that had actually been destroyed in a previous war, as it was blocking the way to more recent devastation. Adham worked hard, picking out stones with speed and efficiency, and throwing them to Asaad without even looking up as he did so. He knew the size and weight of each stone at first glance – a skill he had perfected through months of practice. Having not long established a momentum, with his brother completing the chain down to the cart beneath them, something red suddenly caught Adham’s eye in among the rubble. A toy truck. He stared at it. If we had a real truck, he thought, we’d be able to put a whole day’s stones in it, and not have to go backward and forwards all day with that rickety old cart.

For a moment, the boy forgot where he was and began playing with it among the concrete fragments. He smiled as he pushed it along the jamb of a door, now horizontal, then shook himself and stuffed it into his pocket.‘What are you doing?’Asaad was shouting.‘I’m waiting here. Did you forget about me?’ His voice could hardly be made out against the noise of the bulldozers. The youngest boy cupped his hands around his ear to catch the words. ‘No, I didn’t forget,’ he shouted back.‘I’ll explain later.’

Ayham, the eldest boy, was further afield gathering his own rocks – much larger than the ones being thrown about by his brothers. These were heavy, square chunks of dolomite, used in the older houses or as cladding in the best new builds; great white bricks carved from the quarries of the West Bank. Carrying them hurt his back and left his hands scratched and swollen, but he was getting stronger every day. He felt this. As he worked, he noticed a girl about his age dressed in a blue galabia and a backpack walking towards him from a distance. Each time he set a new stone down on the cart, he looked up at her, surreptitiously, wondering at her smooth, pale skin. But he felt himself blushing as he did so, and tried to work out why he was so embarrassed as he walked back to the heap.

The stones filled up the cart in three distinct piles: the large square blocks Ayham brought, plus two other piles – one of medium-sized rocks, maybe the size of an adult’s hand, the other small enough to fit in a schoolboy’s fist. As Asaad caught the stones thrown down to him, he would quickly decide which of these two piles he should throw them onto. As he did so, he couldn’t help thinking of the three piles – small, medium and large – as somehow representing the three brothers.

Against Ayham’s slow, steady progress to and from the cart, the younger boys seemed to be almost playing. Stones flew between them as lightly as their laughter, with each boy speeding up every so often to see if the other could keep up. Behind their silhouettes, Ayham could see the sun beginning to set; its flaming rays had gathered together and found a new order, just as the stones had found a new arrangement in the back of their cart. Deciding the cart was full, Ayham called his brothers down from their heap. The boys clambered down happily, as Ayham pulled out a large bed sheet from underneath a piece of plaster board. Without a second thought for its original owner, he stretched the sheet carefully over the contents of the cart, securing it to all four sides. Once again, the three boys threw on their backpacks; the youngest, Adham, smiling to himself at the thought of the toy truck now stowed safely in his.

‘Giddy-up, Donkey,’ the oldest boy shouted, as the other two giggled and mimicked him, mustering all the pleasure of a fellah heading back from the fields after a long day’s work.

The boy’s beaming smiles infected passers-by. The younger boys, Asaad and little Adham were pleased with what they’d accomplished, despite the lacework of scratches and scars that covered their soft palms and the tears in their clothes. Only the donkey felt unhappy; it strained against the weight of the rocks the boys had collected. The traffic was heavy, and the cart had to make many stops and starts. Each time it did, smaller stones, having spilled down their pile, kept rolling off the cart from under the sheet. At one point a whole bunch of stones fell out at once, forcing Adham to stop the cart, and his two brothers to jump out and pick them up again. The cars’ honking behind them escalated, drivers’ voices grew angrier. Even pedestrians shouted at them.

‘Do you have a death wish, kid?’ One driver shouted, slapping the side of his door.‘I could barely see you down there. I could have driven over you! What the hell are your parents doing, leaving you to crawl around in the road all day?’

The two boys barely noticed the shouting. Their eyes were glued to the tarmac, scanning in all directions to see where the stones had scattered. A few minutes later they were back on the cart and moving.

‘Hey, boy,’ shouted a policeman pulling up alongside them on a motorbike.‘Dismount this thing and take it off the road, now. I’m issuing you with a ticket.’ Ayham just looked at the policeman, then stared forward at the road again, in silence. The cart carried on. At this, the officer pulled out in front of them, then slowed his bike down, ushering the cart diagonally to the side of the road.

‘Please, sir. Let me go on my way. People are waiting for us at home. They’ll be worried.’

‘You’re too young to be operating a vehicle on the street. And you don’t seem to be aware of the chaos being caused by all the rubbish you’re dropping.’

‘Please, sir,’ this time it was Adham, reaching into his backpack with a somber face, in the cart behind. ‘You can have it back. I won’t do it again, I promise.’

For a moment the officer wasn’t sure what he was looking at: a plastic red truck, with shiny black wheels and a white cabin, was being held out to him by a child who couldn’t be more than seven years old. The man laughed. ‘Keep it,’ he waved. ‘Keep it.’ And before he could gather himself from whatever memory the toy had triggered, the cart was half way up the street.

This time the traffic was clear and the cart began to pick up speed. The donkey was tired but it seemed to understand that they were late. As they sped along, the four of them were a spectacle to behold: donkey and children ghoulishly white, covered as they were in the fine white dust of the rubble; rocks rolling and bouncing in the back in a constant low cacophony. The younger boys, sitting in the back, tried to weather the bumps in the road as best they could; but, each time, their starts of pain and cries of discomfort quickly turned to laughter: a running joke between them was which one of them had the biggest bottom, most able to take the constant prodding and jolting of the rocks beneath them.

As they approached Rimal Street, they spotted a brightly colored cart parked on the pavement, selling biscuits. An old man, presumably the proprietor, stood behind, as a child no more than five of six years old patrolled in front, calling out, ‘Biscuits! Biscuits! Biscuits!’ to passing traffic. The boys couldn’t help themselves. With one dirty shekel fished from the bottom of Ayham’s backpack, they bought a single biscuit. They split it three ways and began nibbling at each piece, savoring its crumbly pleasure as if this were the most expensive biscuit in the world. The scent and softness of the biscuit’s flour seemed to mingle with the dust of their fingers.

By 5:30 pm, the cart had arrived at its destination in the northwest corner of the city, and the three children leapt to the task of unloading the stones. They were paid for their day’s work by a merchant who surveyed the various piles of material that arrived each day. Twenty-four shekels was handed over in return for the stones. Ayham, taking the money from the hands of this grumpy, burly man, made sure not to look him in the eye; a shudder of happiness passed through him, as he gazed at the note and coins in his hands, but it was quickly replaced by a worry: would this be enough to last to the same time tomorrow evening? But then he dismissed this thought too: God provides, as his mother always said.

Finally it was time for the three boys, their wooden cart, their tired donkey, and Adham’s newly acquired shiny red truck to head home. Now empty, their little cart crossed the center of the devastated city, passing half-toppled residential blocks, office buildings pouring out smoke into the night sky, several completely new gaps in the city’s architecture where entire buildings had been flattened.

The boys arrived into Shuja’aya with yells and whistles, their voices echoing through the camp, bouncing off the tin walls of the huts and caravans that had been their neighbors’ homes since the last war drove them out of their farmlands. The cart stopped.

As they ran into their trailer, birds scattered from the hot tin roof above them. Their father lay on his bed, drenched in sweat, barely able to move, as was his fate since an American-made bullet had cut through his spine eight years before. The children planted three gentle kisses on his forehead before going to clean up. The dust still clinging to their faces left white smudges on his skin. Their mother, Om Ayham, sat beside him. By the light of a small candle, she sewed together dresses from a strips of material stacked beside her. Her eyes were tired. Time had left deep etches on her once soft face. The work needed to be completed if she was to be paid in the morning. Returning from the sink, clean and refreshed, the children surrounded their mother hugging her from three sides.

The warmth of her body seemed to restore them from the chill that had crept in since that evening’s sun had set. Ayham withdrew the crumpled 20 shekel note from his trouser pocket, and placed it in his mother’s hand. Her eyes glistened and he gave her a kiss on the forehead. Of the four shekels that remained, he gave two each to his brothers. ‘Don’t forget what I told you. Buy a notebook and a pen so you can learn to write like me,’ he said in his most paternal voice.

– Nayrouz Qarmout is a Palestinian writer and activist. Born in Damascus in 1984, as a Palestinian refugee, she returned to the Gaza Strip, as part of the 1994 Israeli-Palestinian Peace Agreement, where she now lives. She graduated from al-Azhar University in Gaza with a degree in Economics. She currently works in the Ministry of Women’s Affairs.