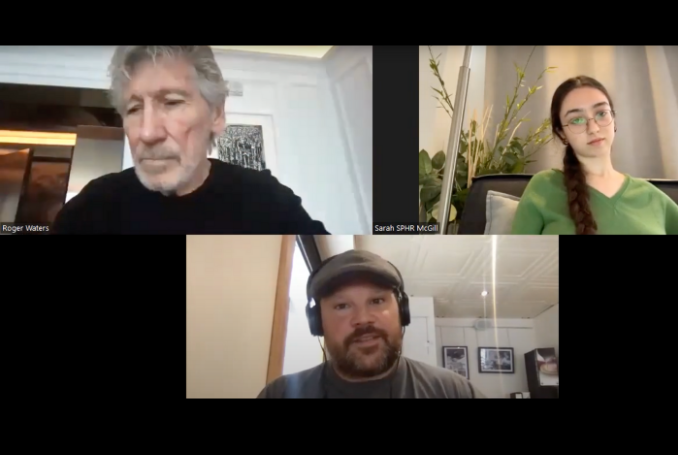

At the recent webinar, “Standing up for student solidarity with Palestine” (hosted by the Canadian Foreign Policy Institute), featured guest and legendary rock artist, Roger Waters, spoke candidly about two troubling experiences he had in Israel. In both, he was initially received graciously by Israelis who were familiar with his creative work. Describing the experiences, he recalled for me how royalty, with exceptional warmth and hospitality, is often received, even by those who have no personal relationship with royalty themselves.

Rogers relates one of the experiences thus (the other, where he visits a film school, he shares here):

“I did…a gig in Israel, which was at a place called Neve Shalom. …It’s an agricultural community where the people who farm the land…are of all denominations. There are Jews, Druids, Christians, Muslims, atheists, whoever. And all their children go to school together and they teach brotherhood and sisterhood. And they teach a sense of community. … [The gig] was incredibly successful. There were about 60,000 people there. What I hadn’t realized at the time was that all of those people, without exception, were Jewish Israelis. They were mainly young people. But they were all Jewish and they were all Israelis. And they were very, very enthusiastic and knew they all my work. …But at the end of the show I made a little speech where I said something like, ‘It behooves you, this generation of young Israelis. to make peace with your neighbors [Palestinians].’ And they went from ‘we love Pink Floyd!’ to [stone cold face]. ‘What the fuck is he talking about? We’re not gonna do that.’ And they were completely silent from that moment on.”

Rogers’ story drove home for me, something I shared with him during the webinar, that niceness or agreeableness is no reliable indicator of deep care for others. Rather, people—by way of expressing such behavior—may be eager to ingratiate themselves to you, hoping you will like them in turn. Hence being favorable to others serves as a way of building positive rapport, making, say, dialogue or communication with them relatively easy.

Yet, as Rogers’ story illustrates, this means nothing as to whether people care about the unjust plight of others, in this case, Palestinians. The moment Rogers asked his audience to think about living with Palestinians, in peace and dignity, they turned their backs on him. This is important too because Rogers did nothing—zero—wrong. He did the very opposite: invited one group of people, namely Israelis, to live in harmony with their Palestinian neighbors.

No doubt that requires work on the part of Israelis, being honest with themselves about both how they, in supporting their government, are complicit in Palestinian suffering and can play a significant role in ending it. But the Israelis of Rogers’ story effectively said “no” to this.

They chose instead to be comfortable, willfully ignorant of the criminal brutality and violence inflicted, by Israel, on Palestinians. The “brotherhood and sisterhood” and “sense of community”, mentioned by Waters, do not for them extend to Palestinians. Likewise, many Israelis would rather enjoy a latte on a sunny Tel Aviv patio, than ever concern themselves with what’s happening not far away: the oppression of Palestinians in Gaza, an illegal open-air prison.

Similarly, Israel might have Pink Floyd fans but many, deep down, are cruelly indifferent to what is happening in the occupied territories. This hardly reflects or dovetails with the creative spirit of music, the essence of which is life-affirming. It favors the well-being of people and the community. It simultaneously rejects death—antithetical to care, love, and humanity.

What Rogers experienced in Israel is not unlike what students at McGill University, in Montreal, have been experiencing from the school’s administration. On March 21 of this year, students, by way of a referendum held by the Students’ Society of McGill University (SSMU), voted well in favor (over 70 percent) of an SMU policy to fully “boycott all corporations and institutions complicit in settler-colonial apartheid against Palestinians.”

In response, the university administration has threatened to pull funding from the SSMU, along with charging that the policy “create(s) excessive polarization in our community, encourage(s) a culture of ostracization and disrespect due to students’ identity, religious or political beliefs, in contradiction with the university’s values of inclusion, diversity, and respect.” If this is true, such “values” include honoring Zionism, committed—in practice—to destroying and erasing the existence of Palestine. McGill’s administration may think that’s ok. Any person of conscience, concerned not only about the human rights of Palestinians but of all, is not.

For the same reason, it ought to be the behavior of the university administration, not the SSMU, that’s checked. The SSMU policy rejects Zionism and aims at dismantling Israeli apartheid that, contrary to international law, systematically oppresses and disadvantages Palestinians. The response of the university administration on the other hand shows it wants this to continue. McGill students, in supporting the SSMU policy, deserve praise for fighting against and not being deterred by Zionism.

Troubling still is what “Sarah” (full name not publicly disclosed), of Solidarity for Palestinian Human Rights McGill (SPHR), shared in the webinar, about the abuse the organization endured:

“Once voting began on March 15 [2022] SPHR members proceeded to inform McGill students about the importance of the referendum, day in and day out. We were tabling and handing out flyers for nearly the entire duration of the campaign time, allotted to students. Dedicated SPHR members, when we weren’t being harassed or being spat on by Zionist student body members—and yes that did happen multiple times—could be seen raising awareness about the Palestinian struggle against settler-colonial, Israeli apartheid.”

Why are these members of the student body not being held accountable? Why hasn’t the McGill administration said nothing to address the dehumanizing treatment against SPHR? It seems that the only time that the administration is prompted to do anything about Zionism it’s never to protect students from its hateful proponents but ensure its rightful critics are disciplined or punished on campus. It’s perverse. All the more so when one considers the longstanding prestige and reputation McGill enjoys, internationally, as a “democratic” and “progressive” institution.

In response to a question I had for Waters, regarding the role artists or musicians can play in holding Israel accountable, he referred me to (and also read at the webinar) “The Road to Damascus.” Reminiscent of a moral tale or parable, it’s written by and from the first-person point of view of Rogers himself:

“Me and this Aussie bloke are walking down the road on the way to a gig. Just as we get there, we see these heavily armed soldiers on the other side of the road knocking this Arab bloke to the ground. Kneeling on him, kicking him in the head, and beating him with their rifle butts.

I cross over to remonstrate with them. The soldiers told me to fuck off or they’ll arrest me. Are you all right? I asked the bloke. A daft question, really. Can I help? Yes, he says. You are musicians? Yes, yes I replied. They have stolen our land, he says. We are resisting them. There is a cultural boycott, please don’t do a gig here.

As he was dragged away toward the paddy wagon, he tossed a small round metal badge in my direction. I returned to the other side of the road where the Aussie has been watching events unfold. Did you see that, I say. Yeah, bummer, he replies. Come on, we got a gig to do. No, I say. There’s a cultural boycott. That Arab bloke is a victim and the soldiers are perpetrators. We have a moral duty to stand with the victim.

Don’t you try and bully me, you shameful cowardly Pommy bastard, says the Aussie, and pushes past me into the gig. I reach down into the dust and retrieve the BDS badge and pin it to my lapel.”

Like McGill, the “Aussie bloke”, notwithstanding the great support of our pro-Palestinian Australian comrades, represents denialism surrounding the ethnic cleansing of Palestine. We must reject and not follow his behavior. Instead like Rogers, frankly the hero in this story, we must also wear the BDS badge. And we must do so in virtue our shared humanity—not as a student, musician or any other social category—aiming to non-violently bring Israel to its knees and help liberate the Palestinian people.

Israel, as an apartheid state, cannot be allowed to exist in its current form. When Zionists charge we are calling for the “destruction” of Israel we must challenge them. Do they mean the elimination of Israel as an apartheid state? If so, then yes; we are calling for that. Do they mean Israel, understood as a home or place for Jewish people? If so, then no; that’s absolutely not what we’re calling for and those who attempt to misframe us as antisemites who want that should, like Israel itself, be held accountable. Not only are they dishonest, they—effectively smearing us as racist “non desirables”—are attempting to prevent others from joining the international struggle for Palestinian justice.

Whether on the road to Damascus or elsewhere, that is a barrier, indeed an evil, that prevents Palestinians and Jews from one day living together—with equal rights, freedom and dignity. Till then each of us has an obligation to fight with Palestine, tearing down the walls that forcibly separate it from the rest of the world.

Israeli apartheid must end.

– Paul Salvatori is a Toronto-based journalist, community worker and artist. Much of his work on Palestine involves public education, such as through his recently created interview series, “Palestine in Perspective” (The Dark Room Podcast), where he speaks with writers, scholars and activists. He contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.