By Benay Blend

On May 29, 2021, HBO premiered the screen version of J.T. Rogers’ play Oslo. It follows a Norwegian couple as they coordinate meetings between the Israeli government and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which resulted in the signing of the 1993 Oslo Accords.

Timely but not impartial, the film comes in a year that has seen Gaza burning under Israeli bombs; prominent activist Nizar Banat’s death while in custody of Palestinian Authority (PA) forces; and hunger strikes among detainees in PA prisons after being detained for several weeks.

In hindsight, a close reading of the roles played by Norwegian diplomat Mona Juul (Ruth Wilson) and her husband, sociologist and Fafo Foundation director Terje Rød-Larsen (Andrew Scott) highlight many of the problems that would arise from the Oslo decision.

The film opens with the couples’ visit to Israel-occupied Gaza where they witness the violence wrought upon Palestinians. At one point Mona watches as two boys, one Israeli, one Palestinian, face each other with what she describes as the same fear. Neither wants to be there, she continues, which was probably true, except that the Palestinian child, with no choice about where he wanted to be, no weapon, no power, faced off against an Israeli soldier who held at least two out of three of those options.

It is this unequal power structure, among other factors, which doomed Oslo from the start. Arafat sent PLO Finance Minister Ahmed Qurei (Salim Daw) along with his aide Hassan (Waleed Zuaiter), while Israel assigned an economics professor Yair Hirschfeld (Dov Glickman) and his associate Ron Pundak (Rotem Keinan).

In his review, Rahul Desai favorably sites what Terje calls “intimate discussions between people, not grand statements by governments.” Yet these participants are on the same footing as the two boys that Mona witnessed in Gaza; one represents a colonized people taking direction from a body exiled in Tunisia, while the other takes orders from the government that is colonizing the other.

Desai also praises what he calls “disarming moments of behavioural humour,” yet, as he later admits, the “Palestinian diplomats appear as caricatures – nationalistic, sentimental, bumpkin-ish, comically stern men,” drawn to mirror stereotypical Western medias. “The Israelis,” he continues, “are the more even-headed and ‘intellectual’ of the lot,” as opposed to the Palestinians.

“Our people live in the past,” Hirschfeld laments. “Let us find a way to live in the present.” With that statement he encapsulates much that is flawed with the film but also Western versions of the “conflict.” “The film, like its Norwegian protagonists,” Desai notes, “operates as a diplomat of its own accord.” In short, it “strives to present an objective view of a traditional conflict,” he continues, but in doing so, it leaves out the Occupation, which has driven Israeli violence since the Nakba in ’48.

Moreover, both the Oslo meetings and the film itself assume a neutral stance. As the late historian Howard Zinn said in the title of his autobiography: You Can’t Be Neutral On a Moving Train (2002), because to do so means siding with the oppressor.

When Hirschfeld calls out another reason for achieving peace, it turns out to be a riff on one of Golda Meir’s more egregious quotes. Translated by the actor Wallace Shawn, Meir was alleged to have said:

“When we kill the children of Arabs, the Arabs made us do it. They hate us so much, they are so angry, that they do things that enrage us and make us kill children. If they were decent people who loved their children, they would set aside their hatred and stop provoking us, and we would then stop killing the children.”

There is no clearer, albeit crueler, way to blame the victim than this, and it was paraphrased by Hirschfeld thus: “You’re fighting is killing your own children,” a line that might have gone unnoticed if it were not so close in meaning to Meir.

In the end, the Israelis call on their foreign minister to acknowledge the treaty, but we learn that Qurei has never been in touch with Arafat as he had claimed. Instead, he was off in another room, staring at the phone for a decent length of time.

Nor do the Israelis have the best interests of Palestinians in their minds. “Pulling out of Gaza would end the Intifada,” Hirschfeld claims, which, in fact, happened, but as outlined in the documentary Naila and the Uprising (2020) was probably a mistake.

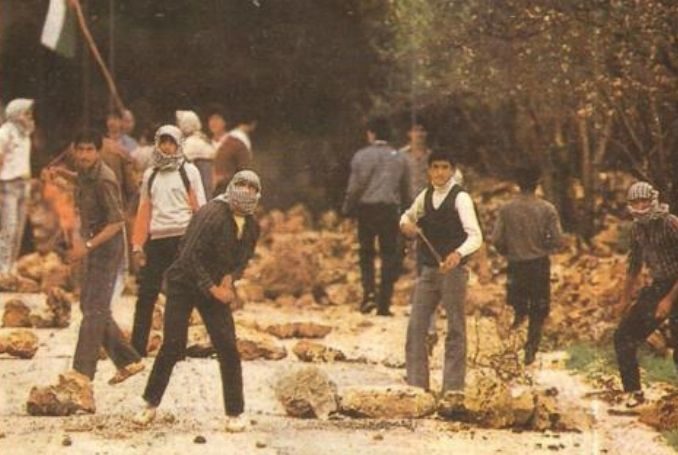

This film follows the story of Naila Ayesh, whose participated in the First Intifada of the late 1980s. Preceding the Oslo Accords, but ending at approximately that time period, the documentary offers another perspective on that time period.

The film opens in 1967 during the Six Day war, a period in which young Naila’s home is demolished, thus setting her on a path towards activism. “The Occupation was everywhere,” she says, in every aspect of daily life, a fact never mentioned in Oslo.

In 1987, Naila joins the Intifada which included women at various levels of participation. Again, in Oslo, the only woman present is Mona, the Norwegian who brings the men together.

This fact Naila brings home at the ending of the film. The Madrid meetings in 1991 she attributes to the actions of grassroots resistance in the streets, but Oslo, she declares, brought much less. Moreover, it did not consult the movement on the ground, including many women, which brought the Israelis to the negotiation table.

In the end, Naila says, the Occupation was still in place, so nothing really changed. This is the same situation today.

In response, Dr. Ramzy Baroud, Palestinian-American journalist and editor of The Palestine Chronicle, and Prof. Ilan Pappé, professor with the College of Social Sciences and International Studies at the University of Exeter, recently discussed their forthcoming book Our Vision for Liberation: Engaged Palestinian Leaders and Intellectuals Speak Out (November 2021).

Moderated by Mark Seddin, a British journalist media adviser in the Office of the President of the 73rd Session of the United Nations General Assembly, also examined whether what has been called the “Unity Intifada” points the way to a new future.

Prof. Pappé declared that these events constituted a “juncture” in the history of resistance in which there is a heightened unity in the face of Israeli aggression. Moreover, the international response was much stronger than expected, all leading to what hopefully will be a united Global South resistance.

According to Dr. Baroud, the book will focus not only on the past but what those lessons can contribute to the future. In particular, he said, Palestinians must work on creating their own framing, their own language, that overrides the official story. In the Zionist scenario, for example, Palestine was portrayed without a people, so that Israelis were absolved of ethnic cleansing. Nevertheless, Zionists created two kinds of Palestinians, he explained, the Good Palestinians, exemplified by the PA, and those who are the “enemies of peace.”

Because Palestinians failed to articulate a unified identity as well as a clear definition of the struggle, they stopped using words like “decolonization,” “liberation,” for as Dr. Baroud explained, they were told it was too confrontational, even though that was the language of movements against colonialism around the world.

According to the book’s announcement, Our Vision of Liberation seeks to challenge the current “dead end” discourse:

“the American pro-Israel political discourse, the Israeli colonial discourse, the Arab discourse of purported normalization, and the defunct discourse of the Palestinian factions. None promote justice, none have brought resolution; none bode well for any of the parties involved.”

Their book, then, fulfills a need to reclaim the narrative within a distinct Palestinian context. Leaving Oslo to molder in the past, the book consists of essays by engaged Palestinian intellectuals and leaders who share a vision of “resistance and liberation” that refuses efforts to negotiate away their rights. “No conditions, no apologies,” declared Dr. Baroud, and in this way encapsulates the core of their forthcoming book.

– Benay Blend earned her doctorate in American Studies from the University of New Mexico. Her scholarly works include Douglas Vakoch and Sam Mickey, Eds. (2017), “’Neither Homeland Nor Exile are Words’: ‘Situated Knowledge’ in the Works of Palestinian and Native American Writers”. She contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.

– Benay Blend earned her doctorate in American Studies from the University of New Mexico. Her scholarly works include Douglas Vakoch and Sam Mickey, Eds. (2017), “’Neither Homeland Nor Exile are Words’: ‘Situated Knowledge’ in the Works of Palestinian and Native American Writers”. She contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.