By Benay Blend

In August 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote a letter in response to a public statement of concern and caution by eight white religious leaders from the American South. January 16, 2023, marks the anniversary of his birthday, celebrated yearly as a Federal holiday in the States. In answer to the charge that problems in the South were caused by “outside agitation,” King replied with his well-known phrase: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” just as much in Birmingham as in Atlanta where he lived.

“We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality,” King continued, “tied in a single garment of destiny…Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider.” In 2022, King’s axiom should be extended to include oppression anywhere in the world, in particular contemporary Palestine.

Last year Israeli Occupation Forces detained approximately 7,000 Palestinians, making it the deadliest 12 months since 2005 for those living under Occupation. In Palestine, detainment is meant to break the spirit of resistance.

According to James Patrick Jordan, Eduardo Garcia, and Natalia Burdyńska-Schuurman, political imprisonment in the United States also serves as a “tool of racist repression” which disproportionately targets people of color along with other participants in the anti-racist struggle. In December 2022, the Alliance for Global Justice compiled a political prisoners list that illustrates how American history, like that of the Zionist state, is “founded and advanced” on the back of racist institutions.

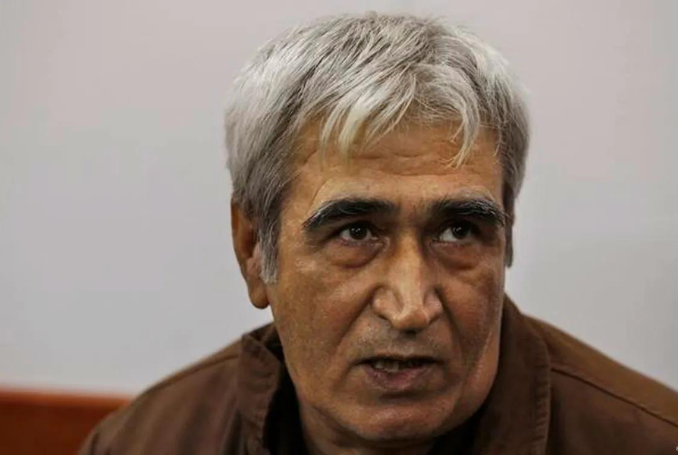

Among long-term detainees in Israeli prisons, the General Secretary of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, revolutionary leader Ahmad Sa’adat, “Abu Ghassan,” has gained attention for his extraordinary sumoud (steadfastness) and principled resistance.

After his arrest, Sa’adat wrote: “The Quartet (US, EU, Russia and the UN) provide a cover for occupation. What happened at Jericho Prison has made the British and US governments an integral part of the conflict and forever buried any illusions (of) their neutrality” – referring to American and UK guards abandoning their posts, allowing Israeli forces to storm the prison, abduct Sa’adat and others, kill two detainees, and injure 23 more.

On the occasion of May Day, 2017, Sa’adat envisioned the movement as a struggle against class exploitation, imperialism and fascism wherever they might exist. “Our message today is to all the revolutionary forces in Latin America and Africa, in the Philippines, Turkey and Greece,” he wrote, “in all the belts of misery and the struggling cities everywhere: the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine [PFLP] stands with you on May 1.” Sa’adat concluded by calling for “the widest left alliance to confront the camp of exploitation and capital and build the alternative, a socialist society.”

Similarly, in a letter dated December 1967, Dr. King expanded the civil rights movement to include not only “the dispossessed of this nation — the poor, both white and Negro” but all oppressed people around the world. Just as Sa’adat viewed the Palestinian camp as the incubator of the revolution and the popular intifada, so Dr. King believed that the “American negro” would serve as “the vanguard of a prolonged struggle that may change the shape of the world, as billions of deprived shake and transform the earth in the quest for life, freedom and justice.”

There are similarities between King’s civil rights movement and Sa’adat’s call for a global anti-colonial movement issued from his prison cell. According to Prof. Rabab Abdulhadi, justice is “indivisible,” meaning that, on the one hand, each struggle is unique, therefore deserving of its own consideration, while on the other, injustice anywhere is a danger to all involved in the struggle for social justice.

Therefore, while the anti-colonial struggle is universal, each movement has its own story, varying according to differences in historical development, preferred strategies, as well as its opposition. Dr. King never wavered from civil disobedience as his strategy of choice. “Nonviolence protest must now mature to a new a new level to correspond to heightened black impatience and stiffened white resistance,” he wrote in 1967. “The higher level is mass civil disobedience” which he hoped would at some point interrupt the function of society.

It is debatable whether he would have changed his mind if he had been allowed to see the country become much less willing to view the demonstrations with a sympathetic eye. As Alexis Madrigal notes, King was a master at using the media to his advantage, but the networks had their own “narrow view” about what the civil rights movement should achieve.

Suffering black people, Madrigal explains, served as an acceptable message, as long as it was white people choosing to give black people a modicum of freedom. “What was not acceptable,” he concluded, “was black people demanding power by any means necessary.” King’s strategy served him well until April 1967 when he began speaking out against the war in Vietnam taking funds away from the war on poverty at home.

“I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today: my own government,” King admonished, words that should be part of every memorial honoring him today.

“In order for nonviolence to work,” said the late Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael), “your opponents must have a conscience.” Having lived his entire life under brutal occupation, Sa’adat understood quite well that the occupier had no conscience in their pursuit of ethnic cleansing. In a 2015 letter from Nafha prison, he called on all popular forces to “sustain and deepen the growing intifada and support its continuation in daily life, altering the nature of the relationship between the occupation and the Palestinian people.

Moreover, he urged “a final end to the path of Oslo, including a full end to all relationships with the occupation.” Sa’adat’s trajectory, focused as it is on revolution rather than negotiations, stands in opposition to King, who favored integration in order to gain civil rights within the system. For Palestinians, that would be impossible given the nature of the occupation.

On December 25, 2022, Samidoun: International Palestinian Prisoner Solidarity Network reprinted a call from Palestine to participate in an international campaign between the 21st anniversary of Sa’adat’s kidnapping. Running from January 15, 2023, through January 24, this week also honors the martyrs of “Operation Cast Lead” in 2008, the Zionist entity’s brutal assault against Gaza, launched the day following the trial of Comrade Sa’adat.

In the words of Samidoun: “Ahmad Sa’adat and the prisoners’ movement are resisting on the front lines of struggle and deserve our effort, work and initiative through all forms of solidarity and support.” The call comes at a crucial time as Itamar Ben-Gvir will soon become the so-called “Minister of Internal Security” for the Zionist project, which includes the prisoners’ files. Indeed, concerned about a High Court ruling in favor of better conditions, Ben-Gvir recently visited Nafha Prison to ensure that conditions had not improved for Palestinian prisoners.

In 2010, Charlotte Kates, Palestine solidarity activist and international coordinator for Samidoun, wrote the following:

“It is incumbent upon those of us who would stand in solidarity with Palestinian prisoners to recognize that administrative detention is one piece of an entire system that exists in order to buttress occupation and undermine Palestinian existence, resistance, and organization. In order to build solidarity, we must refuse to accept as normal or legitimate the criminalization of Palestinian resistance and politics by the Israeli occupation.”

Now more than ever solidarity is important as what Ilan Pappé calls Israel’s newly elected “rogue” Government takes control. While recognizing that no previous entity respected Palestinian rights, he warns that this new government intends to fulfill the goal of the Zionist project “to have as much historical Palestine as possible with as few Palestinians in it as possible.”

In 2018, Sa’adat wrote in the introduction to a reprint of Huey Newton’s Revolutionary Suicide:

“Whether the name is Mumia Abu-Jamal, Walid Daqqa or Georges Ibrahim Abdallah, political prisoners behind bars can and must be a priority for our movements…Political prisoners are not simply individuals; they are leaders of struggle and organizing within prison walls that help to break down and dismantle the bars, walls, and chains that act to divide us from our peoples and communities in struggle. They face repeated isolation, solitary confinement, cruel tortures of the occupier and jailer that seek to break the will of the prisoner and their deep connection to their people.”

During the annual week of action (Jan. 14-24) to free Ahmad Sa’adat, it is the responsibility of all solidarity activists to heed his words along with those of the un-sanitized Martin Luther King.

– Benay Blend earned her doctorate in American Studies from the University of New Mexico. Her scholarly works include Douglas Vakoch and Sam Mickey, Eds. (2017), “’Neither Homeland Nor Exile are Words’: ‘Situated Knowledge’ in the Works of Palestinian and Native American Writers”. She contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.