By Rod Such

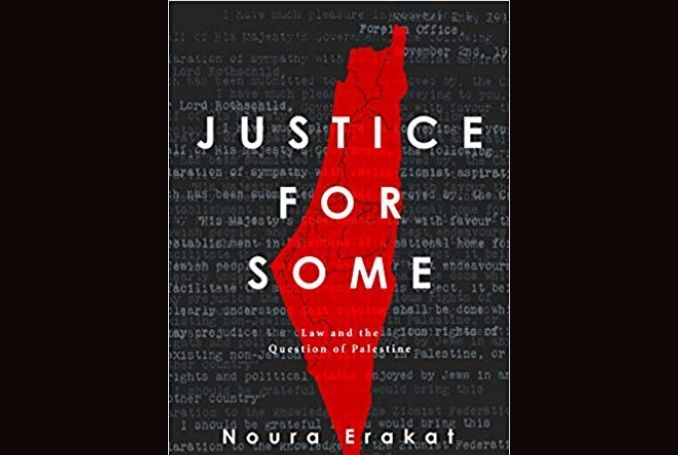

(Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine. Noura Erakat. Stanford University Press, 2019)

The sounds of the bombs that fell on Gaza in November 2019 were almost as deafening as the sound of the silence from the “international community.” That month Israel carried out a targeted assassination of an Islamic Jihad commander and his wife, and the “collateral damage” killed another 32 people, including a family of eight. But the dominant response from abroad focused on Israel’s “right to self-defense,” ignoring both Israel’s execution without trial and the collective punishment of Gazans.

How much longer can Palestinians anywhere believe that appeals to international law and human rights will ever provide them any safety? How can their reaction be anything more than a deep cynicism that international law does not include but rather excludes them? And how will Israel ever be restrained when it knows it will not be held accountable for its violations of international law–in this case death without due process and collective punishment?

The Palestinian-American human rights attorney Noura Erakat, who currently teaches at Rutgers University in New Jersey, attempts to address these and many other questions in her recent book, Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine (2019).

Her answers come at a time when many people reasonably question whether it makes sense to continue framing the Palestinian struggle in the context of human rights law. Some have suggested an alternative framework that understands Israel as a settler-colonial state and the Palestinian struggle as a national liberation movement for self-determination. Granted the two are not mutually exclusive, given that the right of self-determination is also recognized in international law. But has the human rights framework alone with its appeals to the Rome Statute, the Fourth Geneva Convention, and the UN conventions on apartheid, racial discrimination and genocide become little more than an empty exercise in invoking laws that will never be enforced?

Erakat establishes that great power politics and the lack of independent enforcement of international law undermine any likelihood of justice for all, especially for Palestinians. The United States and its allies in the United Nations Security Council maintain a veto power that ultimately protects Israel.

Not only does the United States, as the superpower among the great powers, ensure Israel’s impunity but also if any of the institutions created to address human rights violations, such as the International Criminal Court (ICC) or the UN Human Rights Council, dare to take action on their own, successive U.S. governments have threatened their ability to function. In fact, as this review was being written, the U.S. government announced that it would arrest and sanction any judges or officials of the ICC who might dare to bring war crime charges against U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan.

Given this situation, should the Palestinian struggle continue to invoke international law, especially since much of that law was originally created by colonial powers? Erakat answers this question in the affirmative but with important qualifications. Realizing that international law can be used to dominate, as well as liberate, she suggests that legal advocates of Palestinian rights take their guidance from those engaged in the struggle so that it is grounded in “praxis”–that is, putting an idea or theory into practice. She writes:

“Using international law to advance the Palestinian cause for freedom requires a praxis of ‘movement lawyering,’ where lawyers follow the lead of political movements to buttress their collective efforts. At most, the law can be a tool, and even then, its efficacy will depend on multiple factors. These include geopolitical power, national and international interests, personnel capacity, strategic cohesion, effective leadership, and most significantly, political vision.”

She elaborates by cautioning legal advocates of Palestinian rights “to be more strategic in their efforts, tempering their faith in the law’s capacity to do what only a critical mass of people are capable of achieving.”

Crediting international legal scholar Richard Falk, the former UN Special Rapporteur for the Palestinian Occupied Territories, for the concept, she points to the use of international human rights law as an instrument in a “legitimacy” war-that is, exposing and challenging “the legitimacy of Israel’s policies (removal, dispossession, containment, exclusion, and war) and the assumptions on which they are based (security and sovereignty).”

Similar legitimacy strategies were deployed during the Vietnam War when the antiwar movements in the United States, Europe and around the world called into question not only the immorality of the U.S. intervention but also its violations of the Fourth Geneva Convention and the 1954 Geneva Accord that was supposed to lead to Vietnam’s unification with the holding of national elections. The famous Russell Tribunals, named for British philosopher Bertrand Russell, documented U.S. war crimes and helped undermine popular support for the war.

Of course, the U.S. government and military officials who designed the strategies of massive carpet bombing of civilian populations and “free-fire zones” that resulted in multiple civilian massacres never seriously faced any prospect of war crime tribunals. Ultimately the war ended in Vietnam’s unification primarily as a result of the Vietnamese people’s armed resolve and colossal sacrifice. But the architects of that war did ultimately face “the court of public opinion” and lost, albeit without a unanimous verdict opposing the war as imperialist.

While Erakat rejects the notion of armed struggle as “out of time and place” and easily delegitimized, she is likewise cautious that a strategy solely based on international law is likely to succeed.

“Legal and rights-based strategies,” she writes, “are critical and beneficial, but we should be nonetheless skeptical of their potential. A rights-based approach without a political program that can strategically deploy the law, articulate its meaning, and leverage its yields bears risk and is insufficient to achieve freedom.”

Most of Justice for Some is devoted to the failure of international law to regulate Israel’s behavior during what the author calls “five critical junctures in the history of the Palestinian struggle for freedom.” She argues that the history of international law is mostly a history of the colonial powers who wrote it and who made it primarily “a tool for powerful states.”

Since the 16th century, she notes, “former colonial powers have been the principal progenitors of the international legal regimes governing trade, refugees, human rights, and warfare. International law can be accurately and fairly described as a derivative of a colonial order, and therefore structurally detrimental to former colonies, peoples still under colonial domination, and individuals who lack nationality or who, like refugees, have been forcibly removed from their state and can no longer invoke its protection.”

Only with the 1977 addition of Protocols I and II to the Fourth Geneva Convention did former colonized nations have input into international humanitarian law. One of Justice for Some’s major contributions to the body of human rights literature is Erakat’s primary source interviews with those who played important roles in trying to shape those protocols, such as the legal scholar Georges Abi Saab.

Erakat maintains that the rights of those engaged in armed conflicts as stipulated in Protocol I was eventually applied narrowly, even though its final text did recognize the legitimacy of “armed conflicts in which peoples are fighting against colonial domination and alien occupation and against racist regimes in the exercise of their right to self-determination.”

That international law remained susceptible to colonial and neocolonial influence even in an era of liberation for the formerly oppressed colonial nations of the Global South became apparent with Israel’s use of its sui generis (unique to itself) legal arguments for why the Occupation was not really an occupation.

Moreover, Erakat notes, Israel attempted to establish new “customary law,” such as laying the groundwork for a legal framework that permits extralegal assassinations.

By openly declaring in November 2000 that it had used a helicopter gunship to assassinate Hussein ‘Abayat, a member of the Palestinian Authority’s General Intelligence Service, Israel reversed its previous practice of carrying out assassinations without claiming responsibility.

In doing so, the author observes, “Israel literally created new law for colonial dominance, international law that in the past had been contemplated and rejected.” In doing so, Israel paved the way for other nations, particularly the United States, to openly begin carrying out extrajudicial killings without fear of consequences.

Following U.S. Senate hearings in 1975 into U.S. involvement in political assassinations, known as the Church hearings for Senator Frank Church of Idaho, the U.S. executive branch formally adopted a policy prohibiting such assassinations. But since the “war on terror” began after the Sept. 11 attacks on the World Trade Center, successive U.S. presidents have drawn up hit lists of terrorist suspects, confident that the practice had become customary and acceptable with the example of Israel’s frequent and open use of the tactic.

Erakat notes that unwritten “customary law” is one of the three primary sources of international law. The International Court of Justice, therefore, considers state behavior or what states consider legal (known as national jurisprudence) in determining whether something violates international law.

Thus, Israel succeeded in defining what would otherwise be considered murder as an acceptable practice, even though Israeli human rights organizations and human rights attorneys opposed it vehemently and called it out as execution without trial.

Likewise, Israel’s preemptive attack on Egypt in 1967 helped set the precedent for the U.S.’s violation of Iraq’s sovereignty in 2003 with its “preemptive” invasion to destroy weapons of mass destruction that did not exist.

Justice for Some fails to outline the political vision or program the author believes should guide legal efforts. Given the book’s scope, adding this component likely proved too ambitious. Nevertheless, in calling attention to the role of great power politics, Erakat has suggested what a political program might look like.

If imperialist politics determines not only whether international law will be enforced but also what constitutes international law, then the ultimate solution appears to be changing those politics and altering the nature and behavior of the hegemonic countries.

The U.S. Congress recently voted overwhelmingly to condemn the nonviolent Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement. The resolution’s first Whereas clause read, “Whereas Israel is a strategic U.S. ally…”

This begs the question, An ally for what? What is the strategy? Is the strategy simply to ensure continued U.S. and Israeli military and political dominance of the Middle East? Is the objective to ensure access to and control of a strategic resource, namely petroleum?

That is what the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff proposed in a 1949 memorandum that praised Israel for its military prowess. Given global warming and the necessity to convert from fossil fuels to sustainable energy, most people are capable of understanding that such an objective is diametrically opposed to the interests of the people of the world.

It is literally, as Noam Chomsky put it, a question of hegemony or survival. And for the people of the region, it is a question of freedom or oppression.

– Rod Such is a former editor for World Book and Encarta encyclopedias. He lives in Portland, Oregon, and is active with the Occupation-Free Portland campaign.