By Hatim Kanaaneh

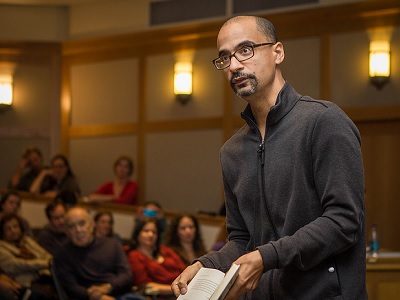

The first night I went to hear Junot Díaz at the University of Hawaii He spoke at the Art Auditorium. I was struck by his intellect and sharp wit. Of course, he doesn’t need me to attest to his exceptional intelligence and creativity; you don’t get to where he has with average scores on those fronts. What I didn’t realize before was what an accomplished performer he is on stage. On both occasions that I heard him he played to a full house of students, faculty and community members. He calls himself “a creative artist“ and I am sold on that.

That distinction was confirmed by the image that I saw briefly from my seat every time he paused to emphasize a point. I sat in the back section of the auditorium and slightly off center. The light from the podium lamp struck his agile form at such an angle that it blurred his face and balding head into one globular splotch. The dark frame of his eyeglasses seemed to float in midair in front of the arc of his bushy black eyebrows. Then there was the central feature, the glint of the flag-like triangular side view of the nose. Below that the hairy muzzle of moustache and goatee danced in synch with the man’s clearly annunciated words. The problem was that he wouldn’t keep still long enough for me to satisfy my fascination with his nose; it must be nearly as big as mine but sharper and straighter. He used his hands a lot. Out of the total darkness below the featureless head a pair of hands would shoot up, sometimes as fists connected to dark forearms and other times as two restless arched sets of fingers threatening to choke the lamppost. I am a doctor and I know I have cataracts but I don’t think what I saw was all a refractory error. I had my good hearing aids on and what I heard went well with what I saw: intelligent, contentious and inimitable.

That first night he read from his one and only published novel so far, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. This flagship of his was enough to thrust him into the global literary limelight. He also read from his second collection of short stories, This Is How You Lose Her. Fascinating! He reads with the practiced clarity and attention-grabbing style of an accomplished actor. My wife, my tireless critic, assesses my own stage reading as middling. She thinks I am much better at narrating than reading. By comparison, Junot Díaz reads and narrates superbly. Perhaps the comparison is not called for. But it is fully intended. Soon I will celebrate my eightieth birthday and I need to scramble vigorously in my attempt to stand on the shoulders of giants. And how many giants are willing to allow their name to be dragged in the mud of Palestine and its BDS morass? Junot Díaz is on record as sticking his neck out and challenging the whole f…ing world on that front:

“If you say, I think the occupation of Palestine is fucked up on forty different levels, people are like, you’re the devil, we’re going to get your tenure taken away, we’re going to destroy you. You can say almost anything else. You could be like, ‘I eat humans,’ and they’ll be like bien, bien.”

Pardon the diversion, but there is more, much more, on that subject. The man is outspoken on the great injustice committed against the Palestinians whether through active genocide, passive collusion or cowardly silence. Yet a friend couldn’t quite believe this claim when I made it. “Look up Junot Díaz in Wikipedia,” he told me. “There is no mention of Palestine in the section about his ‘Advocacy and Activism.’ Not a word!”

I am not sure who is to blame for Wikipedia’s shortcomings. But that clued me about another mystery: why I dwelled more on what I saw than on the content of the lecture that first night. After I attended his second lecture at the UH, this time at close range, I started to ferret out the confused thoughts his striking appearance evoked in me: No one can confuse Junot Díaz with his historical oppressors, the European slave masters. That legacy was even crueler in the Caribbean, where slaves were regularly worked to death, than in the USA. Contrast that if you will with the case of Zionism: Not as openly deadly but genocidal to the Palestinians nevertheless, physically, culturally and memory-wise. And half of its recruited members, the Sephardic half, have my exact features: skin color, nose and fervent hand gestures. Is genocide based on physical features less awful than genocide based on psychological ideation? Is segregation and apartheid harder to suffer when committed by fellow Semites than by the white man? Or is this only my subconscious affirmation of the famed Arab poet’s assertion that: “Oppression from the next of kin is of greater bitterness?”

Answering questions from the audience Junot Díaz waxed combative and self-asserting in a way that only native daughters and sons of oppressed cultures can. Or, as President Barack Obama observed, it must flow from being “steeped with this sense of being an outsider, longing to get in, not sure what you’re giving up.” Of course, the rooting of his novel and basic frame of reference in his black Dominican culture permitted him to dive deep and wide into the rich African belief systems of the Caribbean. He spoke from a personal and experiential perspective that left the field open for each member of the audience to improvise and to adapt to his or her own special experience. The intimacy of his frame of reference was illuminating and convincing. And yet, there was a professorial tinge to his answers, always giving tips, advising and recommending ways for self-improvement. Surely, he was aware that many members of his audience were MFA students thirsty for leads on excellence in writing.

On the second occasion the following day I sat up front as Junot Díaz paraded his stuff. Performing only yards away from me, he had a lively physicality that augmented his thoughts, a bodily interpretation of his scholarly discourse, While being formally introduced by his hosts he stood to one side sizzling, struggling to subdue his motor disquiet. He seemed anxious to get into his act, like an Arabian horse at the ready to take off. Or, to use a more appropriate local simile, like the nervous bubbling of molten lava at the vent of Kilauea between eruptions. Once that restrained energy surged forth in intelligent discourse I could see how demanding the formulating of the conceptions was and yet with what facility the man annunciated them. From my close-up seat I could sense the strain in every fiber of the man’s lithe body as he attempted, successfully I should add, to give the exact configuration to the thoughts he knew and understood. Only he, the hewer of those formed thoughts, could judge their full content and specific gravity. Only he was prescient of the exact flavor and hue of those thoughts issuing from the depth of his conscience. He had to imbue his words not only with the right content and structure but also with the exact dose of reality relatedness. They had to be delivered at the right rate so that we, his audience, would be impacted just so! I sat and observed him pithily laboring at the task of conceptualizing those thoughts and of molding them into the exact words in the unique sequence that rendered them comprehensible to us in the way he intended. Then he would pitch them at his audience with his hands. Or, when he judged the thought needed it, he would add an expletive or two for the right pizazz.

Observing the vividness of his delivery style, the tense facial expressions, the overwrought hand gestures and the restless pacing in front of the audience made me sweat a little. I could only imagine how energy-intensive was his task of mediating between the logic and clarity within his head and the murky assumptions of the laity around him. The effort was even more demanding in light of recent political shifts in America. One can only imagine how strenuous, or likely how enjoyable, and the two are far from mutually exclusive, the task was. He could have read from the prepared text that he had in hand at the start. But he opted for extemporaneous fielding out of his views. For that and for the chance to observe his unique performance I am deeply indebted to friends at the UH, especially to Prof. Cynthia Franklin.

Junot Díaz offers a literary explanation for the current wave of xenophobia in the USA that conflates ‘immigrants’ with ‘terrorists.’ He elucidates his theory by critiquing the longstanding literary genre of the invasion by genocidal foreign hoards. He sees the current dehumanized villains as the Hispanic ‘others’ on the far side of the wall, the existing and the planned wall as in “Build the wall! Kill them all!” You can see how one can easily substitute Moslems or people of color in the readymade equation as long as one keeps the white capitalist masters as the threatened virtuous victims. And how do the neo-liberal art purveyors of the lie at the center of this whole narrative manage to convince so many of their fiction while robbing them blind? By psychological bribery with the bonbon of patriotism and national pride.

His explanation sounded like the absolute truth to this novice to the genre of hate-politics as literature. Yet he managed to end on a hopeful note: look where we, the descendants of slaves and oppressed immigrants, have gotten. We will survive the worst and thrive against all odds. At least in my eyes Junot Díaz’s effort yielded the desired effect. It worked for me at the micro level as well: The end justified the means. His final analysis was worth all the mental and physical effort he invested in explaining it and I invested in understanding it.

– Hatim Kanaaneh is a physician who has struggled for over four decades to improve the health of his Palestinian community in Galilee against a culture of anti-Arab discrimination. He is the founder of the NGO The Galilee Society and the author of the book A Doctor in Galilee and of a forthcoming fictional trilogy. Hi latest collection of short stories, Chief Complaint: A Country Doctor’s Tales of Life in Galilee was published by Just World Books, 2015. He contributed this article to PalestineChronicle.com.