By Jamal Kanj

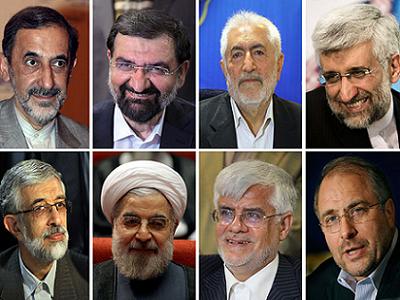

The election landscape in Iran is becoming increasingly clear. According to state-run Press TV, a whopping 686 candidates registered to run in the presidential poll. However, only eight men remain on the ballot for the first round on June 14 after candidates were vetted by the Guardian Council, which consists of 12 members – half of whom were appointed by Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Most are seen as loyalists to Khamenei, while those rejected included former president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and Esfandiar Rahim Mashaie, a close aide to outgoing president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Testing the waters before the Guardian Council’s decision, Iran’s national deputy police commander Esmael Moghaddam sounded a warning last week in the Shargh newspaper for Mashaei to stop challenging the Supreme Leader by claiming to take orders from a higher authority – namely Al Mahdi, the 12th Shi’ite Imam.

There was also an editorial by Hossein Shariatmadari, editor of the state-run newspaper Kayhan and an appointee of Khamenei, declaring the “Ahmadinejad government is over” and predicting “Rafsanjani will undoubtedly face defeat”.

These were the first indications that the current president’s candidate could be purged and a clear sign of how election cards would be stacked to defeat Rafsanjani.

Pundits in the West have argued for years that the method of choosing candidates in Iran’s election is the least democratic.

It is far from being a representation of plural democracy, but neither is the filtered democratic process in the West – where backdoor dealings, not a popular vote, determine which party’s candidate wins a general election.

To the chagrin of the West, the final candidates in Iran might quarrel over many issues, but they all support Iran’s right to develop a “peaceful” nuclear programme.

Other than the new president forming a new negotiating team, there will be little change at the negotiation table once Ahmadinejad is replaced.

Some might take a more pragmatic approach in dealing with world powers, while others are poised to take a more assertive position. Among the candidates still in the race is Iran’s nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili, who said in an interview with the Financial Times that “Western powers will be forced to make compromises only when they are confronted with fierce resistance”.

In past Iranian elections, voters have been more inclined to opt for the nominee who registers lowest on the corruption barometer and has the highest levels of nationalistic demagoguery. Taking a hardline position with the 5+1, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany, would likely improve the presidential candidate’s chances of winning votes.

The irony, which many have forgotten, is that more than five decades ago some of the 5+1 countries introduced nuclear military technology to the Middle East.

France built Israel’s nuclear reactor in the late 1950s and Britain provided the heavy water to start up the plant in 1959.

The highly enriched uranium to make Israel’s first nuclear bomb was purportedly stolen from the US Navy in the mid-1960s.

The West’s inability to reach an agreement with Iran today can’t be separated from its failure in dealing with the crisis in Syria or its submissiveness to Israel when it comes to Palestine.

To succeed, the West must first stop viewing the Middle East through an Israeli prism. Next, it should take bold steps to rectify past sins by promoting a nuclear-free zone in the Middle East.

Otherwise, and as we have learnt from the Iraq experience, Iran will not be the last of the problems.

– Jamal Kanj (www.jamalkanj.com) writes weekly newspaper column and publishes on several websites on Arab world issues. He is the author of “Children of Catastrophe,” Journey from a Palestinian Refugee Camp to America. He contributed this article to PalestineChronicle.com.