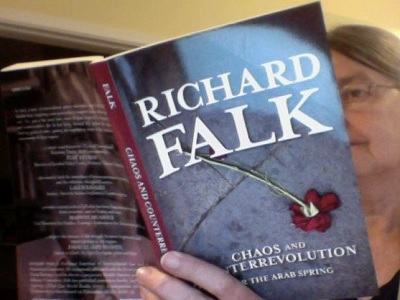

(This feature on Iran is an extract from Richard Falk’s latest book, Chaos and Counterrevolution: After the Arab Spring. Visit Zed Books if you are interested in making a purchase.)

By Richard Falk

I have had a long involvement with the twisting fate of Iran. After the end of the Vietnam War in the mid-1970s, I was fearful that the next site for an American military intervention would be Iran. There were as many as 45,000 American troops deployed in Iran, a country that played a key surveillance role in the Cold War; Iran was a major oil producer and was viewed as a strategic and ideological asset in the region. In 1953 the United States had covertly helped overturn a democratically elected government headed by Mohammad Mossadegh, who had aroused Washington’s concern by repudiating the monarchy and even more so by nationalizing the oil industry. Mossadegh was also misleadingly accused of exposing Iran to Soviet penetration.

This CIA operation led to the return of the Shah and a period of oppressive authoritarian rule that included the torture of all those who dared question the legitimacy and practices of the regime. From an American strategic viewpoint, the Shah was what Henry Kissinger once called that “rarest of things, an unconditional ally.” What this meant concretely was the Shah’s willingness to supply Israel and apartheid South Africa with oil at a time when other oil-producing countries in the world refused to deal with such discredited governments.

Against this background, a movement of opposition from below emerged in 1978 and was in the end led by the Islamic religious leader Ayatollah Khomeini, who had long been living outside of Iran as an involuntary exile.

The movement was largely nonviolent, despite being violently provoked by the Shah’s police and armed forces on several occasions. The challenge directed at the monarchy was not subdued by the brute force of the regime, but rather spread and grew. Khomeini rejected the anguished call from partisans in the streets—”Leaders, leaders, give us guns”—and also rejected compromises and partial victory. The Iranian leader would settle for nothing less than complete victory. Even the Shah’s departure from the country in early 1979 was insufficient. Khomeini demanded, and in due course received, a mandate to rebuild the state from the ground up. Note the contrast with the Arab Spring upheavals in Egypt and Tunisia, which were content to rid the country of the hated ruler but otherwise sought to achieve their democratizing and economic goals through the established order associated with the old regime.

What happened in Iran after the revolutionary forces took over control of the country is complicated and controversial. What emerged was an Islamic theocracy presided over by Khomeini in the role of “supreme guide.” The United States was hostile to these developments, explored military options to reverse the political outcome, and, provocatively, gave the Shah asylum so that he might receive medical treatment. When Iranian students took over the American embassy in Tehran in the fall of 1980 and held its diplomats and staff hostage for over a year, the revolution was radicalized, the opposition of the West stiffened, and moderates, even if devout Muslims, were no longer welcome in the upper echelons of government.

These tensions were further accentuated by Iran’s confrontation with Israel, reversing the Shah’s conciliatory approach. This phase of the conflict was further heightened in the first decade of the twenty-first century by the fiery rhetoric of the Iranian president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, coupled with Western concerns about Iran’s nuclear program. The Iranians have claimed all along that it is an energy program, but Israel and others insist that it is aimed at giving Iran a nuclear-weapons option, which they declared to be unacceptable.

Israel, the only state in the region possessing nuclear weapons, has postured belligerently during the past decade, treating evidence of a nuclear weapons program in Iran as a war-generating red line, and has supported the imposition of harsh sanctions on Iran that exerted severe economic pressure.

More recently Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, has challenged as insufficient President Obama’s diplomatic initiative designed to ensure that Iran’s nuclear program remains peaceful.

This kind of threat diplomacy has persisted, although in light of the turmoil in the region there has been a seemingly serious attempt to reach an internationally supervised arrangement that limits Iran’s reprocessing capabilities in exchange for reducing the pressures exerted by sanctions and gradually normalizing relations. However, Israel’s opposition and the anti-Iranian atmosphere in the U.S. Congress make it difficult to defuse the crisis and explore opportunities for normalization that might contribute to efforts to calm the situation.

There is a troubling double standard that pertains to nuclear weapons and the supposed international treaty regime of nonproliferation.

Israel has been permitted to acquire, possess, and develop its arsenal of nuclear weapons covertly, and is even assisted in doing so by France and the United States. Iran, in contrast, although it was actually attacked in 1980 (by neighboring Iraq, with the encouragement of Washington), has been continuously threatened with a military attack, has experienced efforts at destabilization associated with American and Israeli hostility, and has been subject to a variety of military threats and economic sanctions, is categorically prohibited from acquiring even a deterrent capability.

What is more, the West has refused even to discuss, much less advocate, the obvious means to reduce regional tensions—establishing a nuclear-weapons-free zone throughout the Middle East. There is a perverse consensus that Israel’s nuclear weapons, despite its frequent wars, pose no threat, while Iran is to be stopped from acquiring any comparable capability even if it takes a war to do so. Whatever Iran chooses to do about developing a military capability, it has no prospect of overcoming its total vulnerability to threats of conventional military attack by the United States or Israel. Iran is denied any opportunity to insist on sovereign equality in relation to nuclear weapons to the effect that if it agrees to renounce the option, then others in the region should also be made to do so. The reasonableness of such a demand is underscored by the awareness that Israel possesses a huge military edge in nonnuclear capabilities and has resorted to aggressive war on several occasions to promote its national interests. Under these conditions, it would seem that Iran is entitled to either acquire a deterrent capability or be assured that its main adversary is not allowed to retain and develop nuclear weapons.

In these respects, the encirclement of Iran, reinforced by decades of punitive diplomacy, epitomizes the primacy of geopolitics in the Middle East, as differentiated from a rule-governed system of sovereign states committed to peace and stability. Such an appreciation of these security issues should not lead observers to overlook Iran’s violations of human rights and repressive practices.

– Richard Falk is a world-renowned scholar of international law and former UN Rapporteur on Palestine. (This book extract was first published in Middle East Monitor)