Since the Nakba, Palestinian art and culture have walked a fine line between maintaining tradition and absorbing other modes of expression. After leaving Palestine for Sweden during Israel’s colonizing war of 1967, Nazareth-born songwriter George Totari began to chart a new artistic path, forming the band Kofia with other Palestinians and leftist Swedish musicians.

Between the band’s inception in 1972 and the 1987 outbreak of the Intifada in Palestine, Kofia released four albums, three vinyl records, and one cassette, all without record industry support or major label attention. As a new short film shows, the Kofia story presents a unique mode of grassroots action. This article offers a brief introduction to their recorded work.

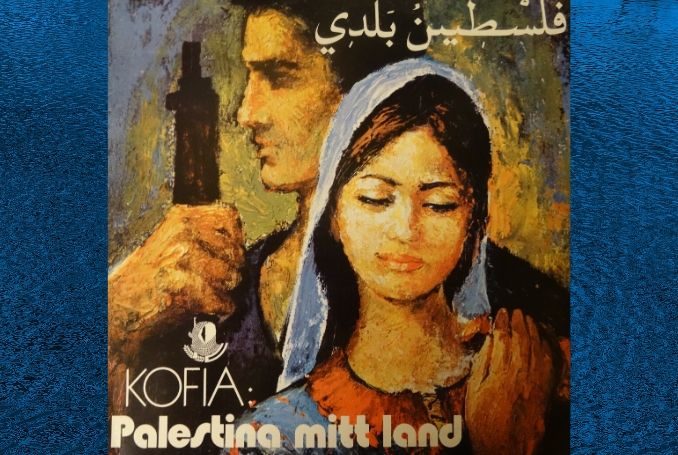

Palestine My Land (1976)

“Fire on the Zionists, imperialists and reactionaries.” Kofia opened their debut album with a militant and daring message, backed up by a powerful rhythmic unison of oud, Greek bouzouki and percussion. Lyrics in Swedish and Arabic sent a defiant message to both the Israeli regime and to its allies among the European ruling classes; Swedish politicians had rolled out the red carpet to Golda Meir, who had recently declared that the Palestinians didn’t exist.

Continuing in the same musical scale maqam kurd, the second song Pansar Och Canoner/Midfa’iyya Wa Dubabat (‘Artillery and Tanks’) took direct aim at Zionist military leader Moshe Dayan, singing from the perspective of a woman whose husband had joined the guerrillas: “long live the people’s revolution!”

If the music and message were relentless, the album notes and photographs offered historical context. They record the words of a refugee woman, Umm Ali on the condition of near-starvation in the Jordanian camps after the 1948 Nakba, saying she encouraged her children to confront the imperialists, Zionists and Arab reactionaries.

There were songs of commemoration for the massacres of Tel el-Za’atar (1976) and Kufr Qassem (1956), the latter ending with lost ones finding “love and protection in the earth.” In Dom Dödar Våra Kamrater/Yiqtilo al-Rifaq (‘They’re killing our comrades’), Totari sings in Swedish, “I long for stones, mountains and valleys.”

The urban soundscape of Gothenburg was a far cry from the rural surroundings in which the Palestinian musicians had grown up, but the blend of instruments, voices and activism offered strength in numbers. The second half of the album was recorded live at Sprängkullen, a leftist cultural center at that time frequented by thousands, and the energy and enthusiasm of the concert participants is audible. Flutist Bengt Carlsson recalls:

“When you came to these concerts, they provided people with rhythm instruments and said, ‘play with us’… people could take part in the concert, which was quite nice.”

On the song Palestinas Dotter/Ibnat Falastin (‘Daughter of Palestine’), a female vocalist leads the battle cry, “No, no, no, no, we will never submit”. On this first album, the musicians’ identities were kept anonymous: “We were doing our duty, our names were not important”, explains Totari.

The album ends with Baladi (‘My homeland’), a traditional song with new lyrics by Totari focusing on the right to return to Deir Yassin, Galilee and Yafa. A repeated melody evokes the improvised sung poetry of Palestinian turathi (‘heritage’) songs. The live recording gives a taste of a vibrant underground music scene, with rhythmic clapping, zaghareet (ululations) and effervescent violin.

Earth of My Homeland (1978)

Thinking back to discussions on the cover of Kofia’s second album, singer Carina Olsson is proud that they chose a photo of a “strong” Palestinian woman baking bread. With no lack of militancy, the band now sang about the fertility of the land, of Palestine’s towns and villages and the strength of steadfast refugee women.

The title track is the first of two odes to Galilee, referencing olives, greenery, and soil. Totari sings in Arabic, calling on the youth of Palestine to rebel against the colonizers, oppressors, and sell-outs (Sadat had just signed a deal with Israel and the US). Next, the Sång om Galiléen/Ughniyya ‘an Jalil (‘Song for Galilee’) sees the oud backing up a female chorus, singing of the vibrancy of Land Day. Totari explains:

“I lived in Sweden and decided that it was my duty to help the Swedes understand our cause. They didn’t know anything about Palestine. Our songs told the stories of historical events, from the voices of mothers who had lost their sons, daughters and everything.”

In Nasaret/Al-Nasira (‘Nazareth’), lyrics by an unnamed ’48 Palestinian are set to oud-led music, with flute lines responding melodically to Totari’s singing of the town he left behind in 1967. The writer describes Nazareth under siege, “while I sang to the winds of a storm”, and promises that Palestinians would one day celebrate their return with a mawwal melody.

The album was also characterized by a strong sense of internationalism; many of the musicians had also been involved in Vietnam and South African solidarity movements. Kofia sang or arranged anti-imperialist anthems dedicated to the people of Chile, Oman and Iran, where the group were invited to perform in February 1980 on the anniversary of the revolutionary overthrow of the Shah.

Earth of My Homeland ended with what is now Kofia’s best-known song, with the Swedish hook ‘Leve Palestina’ (‘Long Live Palestine’) and entitled Demonstrationssången (‘Demonstration Song’)/Tahiyya Falastin on the album. With a catchy repeated chorus, Totari’s composition was simultaneously a manifesto for liberation and right of return, a connection to a homeland and a defiant call for solidarity.

Depicting the wheat and olive harvests, stone and rocket-throwing confrontations with colonization in a now world-renown struggle, female singers led the call and response:

And we will free our land

From imperialism

And we will rebuild our land

For socialism

And the whole world will witness

Long live Palestine!

Crush Zionism!

As if to underline the vitality of the message, Leve Palestina became a staple of left and pro-Palestine protests in Sweden for years to come.

On International Workers’ Day 2019, marchers in Mälmo were attacked by the Swedish Social Democratic government for singing the song: prime minister Stefan Lofven labeled his own party members as anti-Semites for singing the anti-Zionist lyrics and called for the song to be banned.

As in Britain, Germany and other heartlands of capitalism, Palestine solidarity is under attack, yet the songs and stories of resistance continue to resound.

Mawwal to My Family and Loved Ones (1984)

The words and music to Kofia’s third record were composed in dark times, with Beirut ablaze and Israeli-sponsored fascist massacres of Sabra and Shatila still painfully fresh in the memory. But, like the embrace of traditional song, dabke or tatreez embroidery (featured on the album cover) with the renaissance of Palestinian nationalism since the 1960s, Totari’s songs carried a sense of life-affirming celebration:

Clap your hands and dance with me

Your husband is returning today

Drink the arak Ramallah

And eat the tabbouleh, wallah

– Klappa dina händer/Za’af wa ra’s ma’ya (‘Clap your hands and dance with me’)

The song gave space for improvisation by the melodic instruments, offering a vision of freedom with the release of a loved one from prison, with subtly reverbed violin soaring over a droning, pulsating rhythm.

Thematically, Kofia blended vocal support for the armed guerrilla struggle with stories upholding the resilience of the Palestinian masses. In Bomba inte mer/La Tiqtilu al-Atfal (‘Don’t bomb’/‘Stop killing the children’) youngsters are depicted playing together in peace, building new lives and homes for future generations. There are parallels between Totari’s writing and the stories of PFLP leader Ghassan Kanafani, which the songwriter readily admits:

“I got to know his work intimately in Al-Hadaf magazine. Of course, I was influenced strongly by what I read and interacted with.”

The catastrophes of Lebanon weighed heavily on Kofia’s repertoire around this time, mediated through the voices of Palestinians on the front line. The song Södra Libanon/Ijtiyah al-Janub al-Lubnani (‘The invasion of southern Lebanon’) was like an “eyewitness report”, according to Carlsson. For percussionist Michel Kreitem, whose family fled their Jerusalem home in 1948, “every song was a story”.

Bombs came from all directions

From the west, from the east

They want to burn all that exists

We shall fight with all our courage

We shall prevail against fascism and Zionism

Against the devil and all his friends

Long Live Palestine (1988)

A fourth album was recorded amidst the upheaval of the uprising in 1988 and, like the Palestine-based guerrilla musicians of the intifada, Kofia operated on a budget, releasing through the vulnerable medium of the cassette. Totari reflects that “the problem was always resources, no money and so on. The only help we got was from the Swedish musicians themselves.”

Its cover carried the dedication “in memory of the fallen leaders of the Palestinian revolution and of the heroic Palestinian people” and featured Sliman Mansour’s illustration of a dove breaking through the bars of a prison.

Unusually for Kofia, all of the songs were sung in Arabic, with stripped-back instrumentation focusing on Totari’s voice. The lyrical content and can be read as a postcard to those who remained in Palestine, to a land left behind and showing hunger to be involved.

Send greetings to the loved ones and relatives,

To Palestinian eyes and Nazarene eyelashes– Sallem (‘Greetings’)

Love and art

Your beauty, Yaffa

The lighthouse on the beach swaying and seducing

– Jafa

Other tracks are dedicated to Gaza, Jerusalem and Galilee, remembering the community spirit of small-town life, villages, and valleys, and praising the bravery of the youth.

While it would be unfair to earlier musicians to say that the involvement of activist guitarist Mats Lundälv took the Kofia sound to a new level from their third album, there was certainly a difference to the musical arrangements of the fourth.

The 12-string and electric guitar layerings of the riff to Eshtana (‘I’ve missed you’) gives the track a propulsive quality and Lundälv plays a leading role in Malak Ya Assmar (‘You’re an angel, dark-skinned one’), with Mahmod Abu-Elkheir’s Arabic tabla carrying the driving rhythm from song to song.

For Dalal, Peter Jansson’s bowed bass intro borrows from Arabic ornamentation, followed by Carlsson’s vibrato flute and Totari’s oud, which subtly carries the vocal. The lyrics are bittersweet, but hint at the optimism at the heart of the Kofia project:

Salam to your eyes, Dalal

On the wings of a bird, you come to safety

With the blood of the martyr, our soil is watered

Kofia: A Revolution Through Music

At the time of writing, George Totari is leading work on a new Kofia album. The short film Kofia: A Revolution Through Music narrates part of their radical history, as another illuminating example of how Palestinians have dealt with exile, leading a fierce critique of Zionism, imperialism and compliant Palestinian leaders.

By becoming musically and linguistically bilingual, Totari and other leading musicians have led the transmission of Palestinian militancy and socialism. On one level, the coexistence of diverse influences is nothing new, but the dispersal of refugees by the Zionist project has accelerated the process, unintentionally planting seeds of opposition to its own existence.

The Kofia story is still being written. This music will not be silenced.

– Louis Brehony is a musician and activist from Manchester, Britain. He is currently planning research for a book on Palestinian music.

– Louis Brehony is a musician, activist, researcher and educator. He is author of the book Palestinian Music in Exile: Voices of Resistance (2023), editor of Ghassan Kanafani: Selected Political Writings (2024), and director of the award-winning film Kofia: A Revolution Through Music (2021). He writes regularly on Palestine and political culture and performs internationally as a buzuq player and guitarist. He contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.