By Hasan Afif El-Hasan

If I were given the chance to vote in Egypt’s last elections, I would not have voted for the Islamists, but once they won the elections I would give them the chance to rule because establishing a viable democracy over sixty years of dictatorship political rubble takes time.

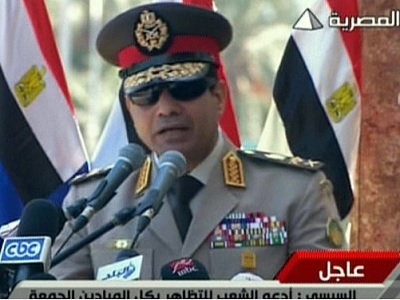

National crises happen in democracies especially in the transition phases, but there are always civil legitimate ways out that do not include military involvement. Military coups offer shortcut to authoritarian rule and they have dangerous security, political and economic consequences. Arab republics in the Middle East and Africa have become too weak economically, politically and militarily under the rule of the generals after a total of fifteen military coups since 1949 when Husni al-Za’im seized power in Syria in a military coup and jailed the elected civilian President Shukri al-Kuwatli.

The Arab republics of the generals have become the ‘banana republics’ of Asia and Africa. Their political, economic and military powers have deteriorated to the point of irrelevance. They have no effective influence on matters relating to Arab causes, locally, regionally and internationally.

They are powerless and complacent bystanders on the violation of Palestinians’ national rights by Israel. They have no power to end the occupation of Palestinian and Syrian lands, stop violations against al-Aqsa Mosque and other holy sites by the Israeli Authorities and the settlers. They were powerless while Israel helped the dismemberment of Sudan. The Egyptian junta today has joined Israel’s right wing parties by declaring contacts with Hamas Party that won the 2006 Palestinian Parliament elections, as acts of treason. In the tradition of all Arab coups, the Egyptian military coup has interrupted the process of more promising new era of building relations with the rest of the world as a democracy on the basis of mutual respect rather than subservient to big powers in the shadow of Israel’s hegemony.

The Egyptian junta has not realized what is at stake when it ordered its soldiers to shoot to kill unarmed citizens for exercising their rights to assemble and protest. The thousands of murdered, burnt, crushed and gassed Egyptians are victims of war-crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity! Violence breeds violence, and the massacres of the anti-coup protesters will increase the prospects for restoring the Islamists’ pre-eminence among the Egyptians. The irony in Egypt is that the Islamists are fighting for the principles of democracy while the Egyptian liberal seculars and many Arab liberals are siding with the junta. World-wide liberal individuals and institutions defend the civil rights of the citizens; they believe the military as an institution has no business in politics; liberals strongly believe that if the citizen does not have free speech that includes the right to protest, he/she lacks a vital part of what to be a human being. But the Egyptian so called ‘liberals’ have enthusiastically embraced military rule and violence against the peaceful anti-coup protesters. Egypt’s armed forces today are the main state actor with absolute authority over politics and unrestrained violence against dissenters; and there is nothing liberal in supporting them and restoring the dictatorship of the generals.

Since the Egyptian seculars have already lost the credibility of preaching democracy, my fear is that the main stream moderate Islamists may lose faith in democracy and the peaceful protest; and as a result, many may join militant Islamists, go underground and Egypt becomes a chaotic and lawless society. After more than eighty-five years of its establishment, the Muslim Brothers (MB) managed to survive even when it was banned under the previous military regimes, and it will survive the current crackdown and the effort to uproot it. Who are the Muslim Brothers?

Egypt was declared a constitutional monarchy in 1923, but the British retained the right to protect the lines of communication through Egypt, and defend Egypt against any external threat. The MB was founded by Hasan el-Banna in 1928 as the first religious-political movement in the modern Arab states to mobilize mostly urban following in large numbers. The movement started in Ismailia City, the most Europeanized of Egyptian towns as a protest against the British occupation and its influence on Egypt’s Islamic culture. El-Banna was a school teacher, an Egyptian nationalist and a charismatic political activist. He viewed Westernization with hostility but he was not against modernization. He established modern educational and social services and used modern mass communications to mobilize popular support. The Muslim Brothers transformed the Islamic movements from the domain of theoretical thought to an organized political movement and from the sphere of individual task to a collective action.

The success of the MB movement under the leadership of el-Banna is attributed to its message which addressed the concerns of those who identified with Islam and felt their identity was threatened by other alien ideologies. It appealed to many groups with different backgrounds in the cities and towns. It attracted grass-root support mostly among the poor class of urban population who had emigrated from the rural areas during World War II. It competed with other alternative ethos in an environment that has been influenced by a mix of the indigenous way of life and European culture and values.

There were three schools of Islamic political thought in Egypt in the 1930s, the traditionalist, the modernizers, and the conservative reformers. The traditionalists including al-Azhar followed a pragmatic policy by compromising with the secular political establishment. The MB belonged to the conservative reformer group that called for the return to the practices of the first Muslim generation traditions. The modernizers tried to explain the tenets of Islam to bridge the gap between Islam and the modern Western culture. The modernizers staffed most of the high education institutions, constitute majority of professionals and politicians, published most of the literature, and edited major newspapers. The signing of the 1936 Egyptian-British Treaty and the Palestinian uprising against the British marked the beginning of the MB involvement in politics. But the penetration of the MB in the Egyptian society started in the early years of its establishment through its social and educational services. It established presence in the form of free essential service for the needy and even the middle class in the private mosques (Ahlia), hospitals, schools, small industries and commercial enterprises.

The MB movement protested against Nasser’s socialist reforms and the 1953 treaty with Britain which allowed the former colonial power to retain presence in the Suez Canal. The MB was dissolved under Nasser by a 1954 order of the Revolutionary Command Council and the order never been repealed. After violent confrontations between the MB and the government, Nasser crushed it and outlawed the movement because he perceived it as a major threat to his secular government. Those who thought that Nasser stamped out the MB once and for all were surprised by its rise from the ashes of the suppression after the 1967 war. The movement was resurrected during the last two years of Nasser’s rule as a protest against the policies that led to the humiliating defeat in the 1967 war. The aftermath of the defeat outraged Egyptians who established stronger identification with the movement than had existed before the war. Many Egyptians saw hollowness in Nasserism and looked for Islam as an alternative ideology.

When Sadat took office, he freed the jailed MB leader Omar al-Telmesani from prison and the MB abandoned violence and espoused a policy of moderate reforms. Unhappy about the leadership’ decision to moderate their opposition to the government, some members who had been expelled from the group accused the leadership of being defeated old men weakened by their imprisonment. The MB support to Sadat did not last long. The MB protested Sadat’s Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty and the vulgarity of his economic ‘infitah’ corruption. Sadat branded it as a threat to his government and felt he would have to suppress. On September 2nd of 1981, Sadat took harsh measures against MB and all groups and individuals who opposed him; thousands were arrested; their political publications were stopped; all mosques were placed under direct control of the government; and the sermons had to be approved by the government. A month later, Sadat was assassinated by First Lieutenant Khalid al-Islambuli who was a member of an Islamic militant group not affiliated with the MB.

After Sadat’s death, President Mubarak sent a conciliatory signal to the MB by releasing their prisoners who had been jailed in the 1981 dragnet. Mubarak’s strategy was to contain the moderate wing of the Islamists represented by the MB. He gave members of the MB the right to participate in legislative politics, but only as individuals or under the umbrella of other parties. MB members accepted to work in the opposition within the system to influence the policies of the government even without having the MB party status. Despite the election restrictions and the harassment by the state security, members from the MB won little more than a handful of seats out of 448 in each assembly election. The MB was the most influential Islamic organization due to its economic and social activism. As back as 1988, the MB ran banks, investment companies, factories, schools and medical and social services. The MB owned among other establishments ‘Faisal Islamic Bank’ that was one of Egypt’s largest banks and they owned ‘Sharikat Tawzif al Amwal’ investment companies with billions of dollars connected to the international economy.

The MB has a history of adaptability that allowed it to survive despite decades of government restrictive laws and intimidation. Since the MB won the elections through democratic process and if the opposition and the military allowed it to rule, its policies would have been more like the ‘Turkish Welfare Party’ rather than the Iranian ‘Khumeinists’ who took power through a popular uprising. And since the economics and politics cannot be separated, the MB capitalists who are heavily invested in the world capitalist economy would prefer the continuity of democracy to the uncertainty and international reactions that may accompany revolutionary changes in government. Resolving the crisis of Egypt’s economy would be the highest priority of their government.

– Hasan Afif El-Hasan, Ph.D. is a political analyst. His latest book, Is The Two-State Solution Already Dead? (Algora Publishing, New York), now available on Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble. He contributed this article to PalestineChronicle.com.

Well written comment. In particular the statement and explanation “The Arab republics of the generals have become the ‘banana republics’ of Asia and Africa.” is very apt.