By Kathy Kelly

Sometimes, I needed to pause and recall my own presumptive conclusions about experiences in prisons and war zones when I had recognized a defining reality, which was that we would eventually return to privileged lives, by virtue of completely unearned securities, related to the colors of our passports or skins.

Salman Rushdie once commented that those who are displaced by war are the shining shards that reflect the truth. With so many people fleeing wars and ecological collapse in our world today, and more to come, we need acute truth-telling to deepen our understanding and recognize the terrible faults of those who have caused so much suffering in our world today. The Mercenary has accomplished a tremendous feat inasmuch as every paragraph aims to tell the truth.

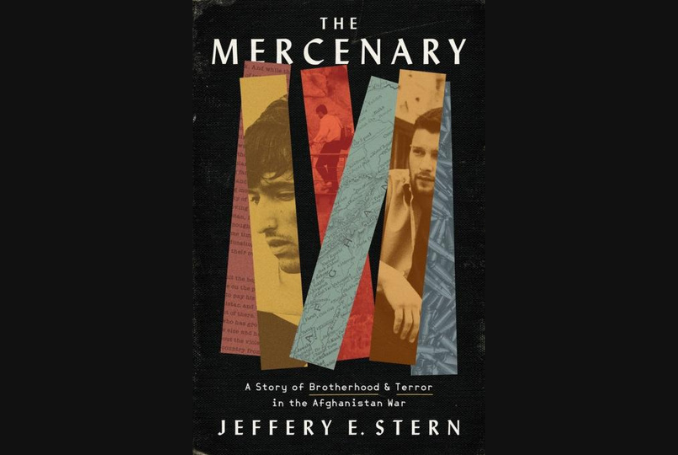

In The Mercenary, Jeffrey Stern takes on the appalling disaster of the war in Afghanistan and in doing so extols the rich and complicated possibilities for a deepening friendship to grow in such an extreme environment. Stern’s self-disclosure challenges readers to acknowledge our limits when we build new friendships, while also examining the terrible costs of war.

Stern develops the two main characters, Aimal, the friend in Kabul who becomes like his brother, and himself, in part by telling and then retelling particular events, so that we learn what happened from his perspective and then, in retrospect, from Aimal’s substantially different point of view.

As he introduces us to Aimal, Stern lingers, crucially, over the relentless hunger afflicting Aimal in his younger years. Aimal’s widowed mother, strapped for income, relied on her innovative young sons to try and protect the family from starvation.

Aimal gets plenty of reinforcement for being cunning and becoming a talented hustler. He becomes a breadwinner for his family before he reaches his teen years. And he also benefits from an unusual education, one that offsets the mind-numbing boredom of living under Taliban restrictions, when he ingeniously manages to gain access to a satellite dish and learn about the privileged white people portrayed in Western TV, including the children whose fathers prepare breakfast for them, an image which never leaves him.

I recall a brief film, seen shortly after the 2003 Shock and Awe bombing, which depicted a young woman teaching elementary students in a rural Afghan province. The children sat on the ground, and the teacher had no equipment other than chalk and aboard. She needed to tell the children that something had happened very far away, on the other side of the world, which destroyed buildings and killed people and because of it, their world would be severely affected. She was speaking of 9/11 to bewildered children.

For Aimal, 9/11 meant that he kept seeing the same show on his rigged-up screen. Why did the same show come no matter what channel he played? Why were people so concerned about descending clouds of dust? His city was always plagued by dust and debris.

Jeff Stern tucks into the riveting stories he tells in The Mercenary, a popular observation he heard while in Kabul, characterizing expats in Afghanistan as either missioners, malcontents or mercenaries. Stern notes he wasn’t trying to convert anyone to anything, but his writing changed me. In about 30 trips to Afghanistan over the past decade, I experienced the culture as though looking through a keyhole, having visited just one neighborhood in Kabul, and mainly staying indoors as a guest of innovative and altruistic teens who wanted to share resources, resist wars, and practice equality.

They studied Martin Luther King and Gandhi, learned the basics of permaculture, taught nonviolence and literacy to street kids, and organized seamstress work for widows manufacturing heavy blankets which were then distributed to people in refugee camps, – the works. Their international guests grew to know them quite well, sharing close quarters and trying hard to learn each other’s languages. How I wish we had been equipped with Jeff Stern’s hard-earned insights and honest disclosures throughout our “keyhole” experiences.

The writing is fast-paced, often funny, and yet surprisingly confessional. Sometimes, I needed to pause and recall my own presumptive conclusions about experiences in prisons and war zones when I had recognized a defining reality for me (and other colleagues who were parts of peace teams or had become prisoners on purpose), which was that we would eventually return to privileged lives, by virtue of completely unearned securities, related to the colors of our passports or skins.

Interestingly, when Stern returns home he doesn’t have that same psychic assurance of a passport to safety. He comes close to emotional and physical collapse when struggling, along with a determined group of people, to help desperate Afghans flee the Taliban. He’s in his home, handling a barrage of Zoom calls, logistical problems, and fundraising demands, and yet is unable to help everyone who deserves help.

Stern’s sense of home and family alters, throughout the book.

With him always, we sense, will be Aimal. I hope a broad and diverse number of readers will learn from Jeff’s and Aimal’s compelling brotherhood.

–Kathy Kelly, a peace activist and author, co-coordinates the Merchants of Death War Crimes Tribunal and is board president of World Beyond War. She contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.