‘Miriam and Youssef’ is a 10-part radio drama from the BBC World Service about the founding of the state of Israel between the years 1917 – 1948. The story is narrated by the two central characters, Miriam Cohen, a young Jewish refugee from Poland, newly arrived in Palestine with her mother, and Youssef Bannourah, a young Arab from the village of Deir Yassin. The latter is not very good at the family trade of stonemasonry but is fortunate to acquire a mentor in Sgt Harry Lister, British Custodian of the Holy places in Jerusalem. Also featured is Yeshoah, a radical young Zionist kibbutznik who eventually marries Miriam. Some historical figures appear later as the drama develops.

The activities of this central group stretch plausibility at times as the series attempts to portray the violent and complex story of the British Mandate in Palestine. The eponymous pair lurch from peaceful idealism to terrorism and back. The Jewish mother is constantly mithering. Youssef’s father, who expresses Uncle Tom attitudes towards Britain, later becomes patsy for the manslaughter of a Jewish woman when men from the village in attack a neighboring kibbutz. Harry Lister is sent home in disgrace after the 1929 riots but apparently succeeds so well at his desk job that he returns five years later as Assistant Director to the High Commissioner, sporting the rank of major.

On the feedback program ‘Over to You’, Commissioning Editor Simon Pitts, suggested the series “may help people understand a little bit more about today’s situation by just understanding how it all came into being”. His belief was shared by a listener from Dublin, who considered the series “very educational for me”. This confidence is encouraged by the program’s website which declares “Every effort has been made to ensure that the series is culturally, linguistically and historically accurate”.

Regrettably, BBC Middle East reportage is not always accurate. In 1953 the BBC broadcast propaganda opposing the nationalization of British oil assets in Iran, causing the Corporation’s Iranian broadcasters to go on strike. BBC Panorama’s 2010 documentary on Israel’s raid of the Gaza Freedom Flotilla was so consistent with the Israeli narrative that the normally sensitive Foreign Ministry downloaded the entire program onto its website. A photograph published by BBC News in 2012 purportedly showing bodies of victims from a chemical attack in Syria was actually taken in Iraq nine years before. Any BBC journalist who states that West Bank settlements contravene International Law invariably adds the appendage “although Israel disputes this’, as if this somehow negates Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention.

So has the series managed to match achievement with aspiration? In outline yes, but there is much devilment in the details, particularly those that have been omitted. Despite the first episode being entitled ‘the Twice Promised Land’, only one of the promises is featured, namely Balfour’s infamous Declaration. Nothing is said of the Arab Revolt of 1916 to 1918 against Ottoman forces in the Arabian Desert, fought in response to Britain’s promise to recognize an independent Arab kingdom after WW1. (The inclusion of Jerusalem, and hence Palestine, would have been essential to induce Arab tribesmen to ally themselves with infidels and fight the Turks.) In 1920 the Palin Report admitted that Allied declarations deliberately fostered this belief among Arab opinion. In 2020 the BBC conceals this fact.

Even the Declaration itself is only mentioned in part. Britain’s promise to support a Jewish National Home in Palestine is quoted, but not the guarantee to safeguard “the civil and religious rights of the existing non-Jewish communities”. Incorporated into Britain’s mandate for Palestine, and central to the 20th-century history of the Middle East, the Balfour Declaration comprises only 68 words. Yet only a truncated version is included in this drama of over four hours duration.

British politicians had promised Arabia to the Arabs in 1915; in 1916 they secretly agreed with France to carve up the Middle East between them after the war, and in 1917 Britain promised an undefined area of Palestine to the Jews. After Allenby’s forces had conquered the whole of Palestine in early 1918, all previous pledges became subject to British interpretation. And Britain’s political leaders intended to keep control of Palestine indefinitely, albeit with Jewish settlement into this Arab land. Balfour’s Declaration gave a moral pretext to the imperial strategies of protecting the Suez Canal and constructing a pipeline between the Iraqi oilfields and the port of Haifa.

Consequently, the Declaration did not mention a Jewish state or commonwealth, nor did it define the borders of the “Jewish national home”. Nevertheless, this vague promise allowed Britain to secure the Palestine Mandate from the League of Nations. One result was wholesale disillusionment in Arab communities. Arab confidence in British intentions as expressed by Youssef’s father in the first episode lasted for only a few months. Once the reality of British intentions became apparent, ninety percent of the Arab population turned hostile to the British Administration. Perversely, Youssef and his father are portrayed as believing in British intentions long after the majority of their peers.

The concept of using fictional drama to portray one of the most important political histories of the twentieth century was problematic. Aiming to be historically accurate at the same time was nigh impossible, especially when the join between fiction and fact is seamless. Obviously Miriam cycling through Jerusalem is fictive, but is the villager’s attack on an unnamed kibbutz during the 1929 riots fact or fiction? According to historian Hillel Cohen, quoting a contemporary Jewish source, the Jewish neighborhoods of Giv’at Sha’ul and Beit HaKerem were attacked when

“…some 30-40 Arabs were seen on the descent from Deir Yasin opposite us. They went down into the valley and prepared for an assault. A group of Jewish defenders hid at a corner on the slope down from Beit HaKerem and began to shoot at them, without hitting any…The exchange of gunfire continued until 8:30 [six hours duration]. In the meantime, several machine guns arrived with the English army. A machine gun was set up and opened fire in the direction of Deir Yasin. The soldiers took a local car, drove to the village, and opened fire on Arabs and then came back…on the Jewish side several were wounded over Friday and Saturday in Giv’at Sha’ul. One (Ya’akov Leib Dimentstein) was badly wounded and died.”

In the BBC story (for which no sources are given) the mukhtar and a body of men attack an undefended kibbutz. They kill the animals, smash up the property and set fire to the buildings. A bedridden geriatric Jewish woman dies in the fire. The mukhtar was not responsible for lighting the fire, but is arrested by Sgt Lister and subsequently convicted of manslaughter.

In all this how does a listener decipher where historical fact becomes ripping yarn, and how can the apparent inaccuracies help the stated purpose of the series to understand more about today’s situation? One might generously concede that the attack took place and pretend that the details are unimportant. But that is not a sound basis for understanding an ongoing regional conflict. Therein lies a dilemma: historians struggle with complexity, of which there is plenty in Levantine history, while drama needs a straightforward narrative. The result in this instance is a historical yarn vitiated by significant omissions of historical record, which need further explanation.

The war in the Levant brought misery to the entire population: the 1915 locust plague plus the Allied naval blockade (intended to starve the population into submission) caused widespread famine. Diseases followed (including cholera and typhus) killing thousands. Military conscription and requisitions added further to the civilian plight. These miserable conditions are not evident in the drama (one might recall the Mukhtar’s daughter, regarded as the least important member of the household, getting a second helping).

Disillusionment and fear of dispossession fuelled Arab unrest which, as related in the program, first turned violent in 1920. However, there was also concurrent Jewish violence against Arabs, particularly by followers of writer and political activist, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, founder of the Revisionist movement, who campaigned for a greater Israel on both sides of the Jordan River. The inclusion of only Judah Magnes, a pacifist, as an early influence on Zionist thought (plus mention of Aaron David Gordon, who counseled good relations with Arabs) is misleading.

British repression is featured in the story, but its scale and barbarity are understated. After anti-Zionist rioting in 1920 and 1921, Winston Churchill cheaply recruited former auxiliary members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (the infamous Black and Tans) to form a Palestine gendarmerie. Described by the chief of the imperial general staff, as a “gang of murderers”, they were hated and feared in Ireland, until IRA targeting forced many to leave. In Palestine, they reverted to their previous habits, with baton charges and shoot to kill policies. Civil unrest peaked during the years of the Arab Revolt (1936 – 39). The British response (described in Episode 5 as “moderation”) included torture, population cleansing, collective punishment, human shields, judicial and summary executions, and exile. In 1936, 6,000 inhabitants in Jaffa alone were thought to have been made homeless by punitive house demolitions. By 1939, over 9,000 Palestinians were held in internment camps. That same year ten men died at Halhoul, near Hebron, after British soldiers kept them in a cage for seven days without food or water.

Episode 6 on ‘The Death Ships’, concentrated on the SS Struma which was torpedoed in the Black Sea in 1942 after being refused permission to reach Palestine. All but one of the 769 Jews on board perished. Another death ship was unreported. In 1940, 1,770 Jews were put on board the SS Patria at Haifa for deportation to Mauritius. The Jewish paramilitary organization, Haganah, intended to prevent the sailing by crippling the ship with a timed explosion. Instead, the decrepit and rusty vessel sank within 15 minutes, killing more than 200 people, mostly Jews.

Miriam’s quote (episode 7) of Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin on 13 November 1945, ignores the context. It referred to 100,000 Jews living in appalling conditions in European camps for displaced persons. Ben-Gurion had forcefully demanded that all be allowed to enter Palestine and for the entire territory to be declared a Jewish state. (At the same time offers to rehabilitate small numbers in Europe were strongly rejected by Jewish leaders.) These demands were supported by strong pressure from US President Trueman, who declined to offer assistance. Palestinian Arabs held Christian Europeans responsible for this misery, and felt they were unfairly expected to provide the relief. Bevin sought to fulfill Balfour’s promise to safeguard Arab civil rights and feared the proposals would cause increased civil unrest which Britain, then destitute, would have to control alone.

In 1946, as the story of the Jewish insurrection continues, Miriam opines that “the Irgun which [Menachem Begin] commanded was about combat, not terror”. Certainly, the perpetrators regarded their attacks this way, but the narration of a documentary-drama should not legitimize extreme opinions of dangerous fanatics, be they Arab, Jew or British servicemen. Begin’s Irgun were reckless about civilian casualties (as the narrative of the King David Hotel bombing illustrates) and they targeted railway workers because the railways transported troops and munitions. Such political violence against protected persons has correctly termed terrorism or, as Christopher Sykes described it, “the most repulsive form of gangsterism”.

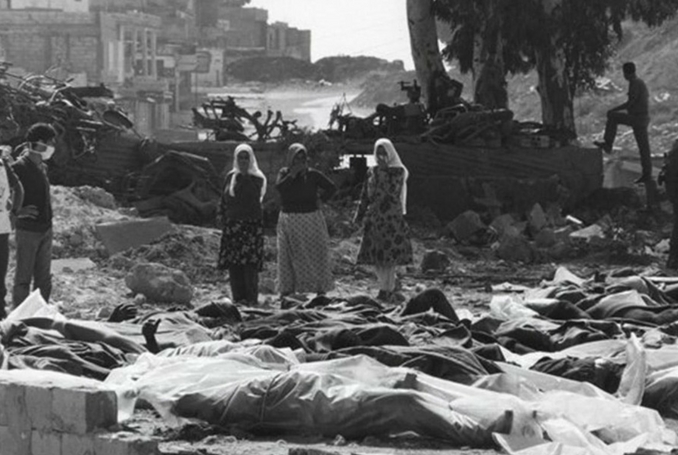

Reflecting on the Deir Yassin massacre, Miriam comments: “I don’t think anyone knows exactly how or why the battle became a massacre.” Writing in 1998, Meir Pail explained “Only long after, it turned out that Lehi had initiated the idea of the raid. […]In the course of planning discussions, the Lehi people suggested a massacre, but the Etzel people objected.” (Meir Pail had contacts with the Haganah intelligence service and was present as an observer for the Haganah. Although his account is disputed by perpetrators from within the Irgun, it was endorsed by Yisrael Galili, former head of the Haganah.)

Five days after the Deir Yassin massacre a Jewish medical convoy with supplies and medical personnel was attacked on the way to Mount Scopus hospital. The BBC details are correct, but events were more complex according to Jacques de Reynier, Head of the Red Cross delegation in Jerusalem. Mt Scopus was also a Hagannah base, and the convoy was armed. An offer to put Mount Scopus under Red Cross protection on condition it be demilitarized was declined by the hospital leaders. The day after the massacre, M. de Reynier demonstrated that Arabs respected the Red Cross when, without prior notification, he led a small column of vehicles through Arab territory under the Red Cross flag. No shots were fired.

As a drama ‘Miriam and Youssef’ succeeds, and fulfills the high standards of BBC radio, although sometimes it was hard to decipher the yells, screams, and bangs. For example, in episode 5 it was unclear if Harry’s driver had been shot dead, and just how Harry thought he could get Youssef out of this mess. But as a didactic history, it is flawed. Historical accuracy cannot be nearly accurate, or accurate most of the time, and this drama presents an unreliable tale tainted by insidious inaccuracies. Much of the fault lies in the decision to teach history using drama. Not only does this waste time (by recounting that Harry Lister is lonely, by hearing Miriam being seasick and other trivial flights of imagination), it also confuses the listener and infuriates the scholar. Those who make historical drama should respect the complexities and limitations and not attempt to achieve the impossible.

– Richard Lightbown is a British human rights activist and researcher who writes articles on Middle East topics for various online publications. He contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.