By Jeremy Salt

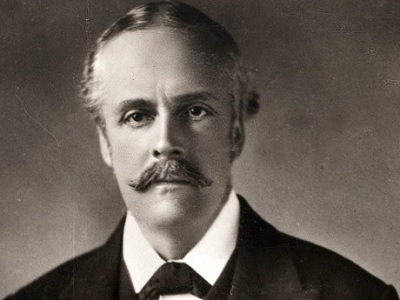

Even his contemporaries had trouble working out Arthur James Balfour. Aloof, privileged, extremely wealthy, the product of Eton and Cambridge, he clearly liked power and being at the center of things, without liking the boring detail of hard work. He once said that ‘enthusiasm moves the world’, without showing many signs himself of being interested in much: his enthusiasm for Zionism appears to have been an exception. ‘Nothing matters very much and few things matter at all’ was another of his aphorisms. Behind the urbane, public image, he took pains to hide the private Balfour, whatever that was. A biographer of British Prime Ministers, Harold Begbie, wrote that he ‘has said nothing, written nothing, done nothing which lives in the hearts of his countrymen. To look back on his record is to see a desert …’

Balfour’s political and social connections were impeccable. On his mother’s side he was a Cecil: Lord Salisbury, Foreign Secretary and Prime Minister (on two occasions) in the late 19th century was his uncle. Balfour himself, throughout his political career as a member of the Conservative Party, served as Chief Secretary for Ireland, Secretary for Scotland, Lord Privy Seal, First Lord of the Admiralty, Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary, the position he was holding when he signed the Balfour Declaration.

A lifelong bachelor, Balfour still fathered one disturbed child, the state of Israel. Palestinians, the Middle East and the world generally have had to live with the consequences ever since. Visiting Palestine in the 1920s for the laying of the foundation stone of the Hebrew University, he moved on to Damascus, and could not understand why the locals were angry. Besieged in his hotel room by demonstrators he saw nothing of the city, had to be surreptitiously whisked out of the hotel by a side door before being driven at speed across back roads to Beirut, from where he took passage on a ship and sailed away, still unable to understand why his visit had caused such a fuss among the Arabs.

Balfour is an interesting example of the coin with two sides, one philo-semitic and the other stamped with the familiar verbal characteristics of anti-Semitism. Philo was on display in 1917 with his emotional declarations in support of the role he was playing in what was routinely described as the return of the Jewish people to their ancestral homeland. Anti reared its head in 1905 when, as Prime Minister, he spoke in support of the Aliens Bill, whose specific purpose was to prevent Jewish refugees fleeing pogroms in Russia from entering Britain.

It was not as if the Jewish presence in Britain was a new issue. In 1218 England’s King Henry III had issued an edict requiring Jews to wear a badge identifying them as Jews. In July, 1290, King Edward issued another edict, expelling all Jews from England, a total number probably of about 2000. Many appear to have moved to France or the Netherlands. Others went north to Scotland. Some apparently managed to find their way back, taking anglicized names, but officially, they were banned until Oliver Cromwell allowed them to return in 1657.

In the late 19th century increased Jewish immigration drove the debate which led to the passage of the Destitute Aliens (Immigration) Act of 1893. In the Commons references were made to the ‘evil’ of the immigration of ‘alien paupers’, the agitated state of public opinion and demands that such immigration should be ended forthwith. Compared to the presence of established anglicized middle class Jews, it was pointed out that Yiddish-speaking newcomers were forming ghettos in East London, Manchester, Leeds, Liverpool and Glasgow.

A government report published in 1894 referred back to 1886, when ‘conditions’ in the East End had become an issue of public interest and statements were made to the effect that a ‘colony’ had come into existence of foreign laborers prepared to accept lower wages and work long hours as the price of living in Britain. Their numbers were continually increasing, competition for employment leading to a situation of ‘sweated’ labor in London and other cities.

The census of 1881 had shown that fewer than 15,000 ‘Russians or Poles’ were living in England and Wales, a figure not defined but apparently referring to recent immigrants and not British Jewish citizens. There was evidence of a considerable ‘inflow’ since then, clearly connected with the 1881-84 wave of pogroms that swept Russia following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II. Statistics were produced to show the increase. In East London ‘whole streets and areas in Whitechapel, St George’s-in-the-East and Mile End Old Town were nearly monopolized by the foreign Jewish colony.’

In the 1894 report it was found that the appeal of these ‘congested districts’ to Russian and Polish immigrants had not diminished. Evidence suggested that the ‘foreign Jew’ was ‘not popular as a workman among English workmen. He is thought (not without some reason) to have no feeling for the dignity of his trade, to care little for the general standard of its organisation and to evade any agreement generally arrived at for its improvement.’ Generally speaking, however, it was concluded that ‘foreign Jews’ were a peaceful and law-abiding community.

In 1895 the passage of an anti-alien resolution at the Cardiff Trade Union Congress was countered with A Voice from the Aliens, published by ‘Jewish Workers of England’ and protesting against the ‘untruthfulness’ of the ‘uncomplimentary remarks’ made by some of the delegates. ‘It is and always has been the policy of the ruling classes to attribute the sufferings and miseries of the masses (which are natural consequences of class rule and class exploitation) to all sorts of causes except the real ones. The cry against the foreigner is not merely peculiar to England: it is international. Everywhere he is the scapegoat for other’s sins. Every class finds in him an enemy.’

In 1902 the government established a royal commission into alien immigration. The issue had reawakened public interest, leading to protest meetings demanding further restrictions on the immigration of ‘destitute foreigners.’ Jewish organizations, including the largely Jewish Federated Tailors’ Union, put forward counter arguments. In 1905 the tabling of the Aliens Bill in parliament maintained the momentum of the debate, in which Balfour took a leading role in drawing attention to the negative consequences of an alien immigration ‘which is largely Jewish.’

If this continued without check, Balfour said,

‘a state of things could be imagined in which it would not be to the advantage of the civilization of this country that there should be an immense body of persons, who, however patriotic, able and industrious, however much they threw themselves into the national life, still, by their own actions, remained a people apart, and not merely held a religion differing from the vast majority of their fellow countrymen, but only intermarried among themselves.’

These somewhat veiled sentiments had been expressed openly in the 1890s when, visiting Bayreuth, Balfour remarked to Cosima Wagner, the widow of Richard, that he shared ‘many of her anti-semitic postulates.’ He referred to this encounter much later in conversation with Chaim Weizmann: if the point was how much he had changed since the 1890s, his statements in support of the Aliens Bill and his remarks to David Lloyd George much later, that Bolshevism could be traced back to the Jews and that they constituted a ‘formidable power whose manifestations are not always attractive’ indicated that, beneath the surface, he had not changed much at all.

During the war he refused to intervene with the Russian government against the mistreatment of Jews in the Pale of Settlement: as Russia was an ally he had good reason for this but his ambivalence on the ‘Jewish question’ was still clear. While he believed that treatment of Jews could be abominable, he also believed that their persecutors ‘had a case of their own.’

In conversation with the Jewish (and anti -Zionist) journalist Lucien Wolf in 1917, he remarked that the persecutors of Jews were afraid of them: ‘the Jews’ were an exceedingly clever people and wherever one went in Eastern Europe,

‘one found that by some way or other the Jew got on, and when to this was added the fact that he belonged to a distinct race and that he professed a religion which to the people about him was an object of inherited hatred, and that, moreover, he was … numbered by millions, one could perhaps understand the desire to keep him down and deny him the rights to which he was entitled … he did not say this justified the persecution but all these things had to be considered.’

The timeline in the early 20th century is significant. On July 7, 1902, in London, Herzl gave evidence to the Royal Commission on Alien Immigration. On October 22-23, he met the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, Joseph Chamberlain, to discuss the establishment of a Jewish colony at Al Arish, in the Sinai peninsula, among various possibilities then being considered. In December, 1902, Chamberlain visited the British East African protectorate to discuss railway construction and colonial settlement, which was not growing as quickly as he had hoped. Between January 15-22, 1903, Herzl met senior British government officials to discuss the establishment of a commission to inquire into Jewish settlement at Al Arish. On March 27, in Cairo, he took up the subject with the Britain’s Egyptian proconsul, Lord Cromer.

On April 19-20 (April 6-7 on the Russian calendar), 1903, anti-Jewish mobs ran amuck in Kishinev, now Chisinau, the capital of the Republic of Moldova but then in the Russian governorate of Bessarabia. Almost half the city’s population was Jewish. After nearly three days of rioting, 49 Jews had been killed, women had been raped and a mass of Jewish property had been destroyed. The pogrom precipitated a flight of Jews towards the west, many heading for Britain.

On April 24, 1903, in London, Herzl had a meeting with the Foreign Secretary, Lord Lansdowne, and Chamberlain, who raised the possibility of Uganda as a location for Jewish settlement. Chamberlain had already thought of Finns and Indians as possible settlers: the commissioner for East Africa, Sir Charles Eliot, regarded the Finns as a maritime people whose settlement in East Africa would be completely unsuitable, while, whatever Chamberlain had in mind, white settlers would clearly resist any large-scale settlement of Indians.

Between May 11-13, 1903, Herzl was told the Al Arish project had collapsed, having been rejected by the British-dominated Egyptian government. In this period the Zionists continued to negotiate with Russia, through the anti-semitic Interior Minister, Vyacheslav von Plehve, and even with the Ottoman government. On August 14, 1903, Chamberlain offered the Zionists a form of autonomy in Uganda. On August 26, meeting in Basel, the Sixth Zionist Congress accepted the British offer on a vote of 295-178, with 98 abstentions. Herzl himself had spoken in favor, making it clear, however, that East Africa could only be a way station on the road to Palestine.

The congress established a commission to check out the lie of the land in East Africa. It had three members, Nahum Wilbusch, a Russian civil engineer, Alfred Kaiser, a Swiss scientist and explorer, and Major A. St Hill Gibbons, an African explorer and leader of the expedition. Only Wilbusch was Jewish. ‘Uganda’ was in fact Kenya. The 5000 square miles on offer, about 16,300 square kilometers in the cool highlands on the Uasin Gishu plateau, was prime land for colonial settlement and agricultural development. What Chamberlain had in mind was an autonomous colony with a Jewish governor but ultimately responsible to the government in London.

The news outraged the white settler community. This was their land, after all, they fumed. Lord Delamere, the president of the Planters and Farmers Federation, which had applied for an allocation of land in the region offered to the Zionists, sent an infuriated letter to The Times complaining of this plan to settle ‘undesirable aliens’ and ‘alien Jews’ in the protectorate. The flood into Kenya of people of ‘that class’ was sure to lead to trouble ‘with half-tamed natives jealous of their rights.’ In fact the ‘natives’ had nothing to do with this project. What they might have thought was completely out of the picture: all the ‘jealousy’ was coming from white settlers jealous of their ‘rights.’ The Kenyan highlands were ‘white man’s country.’ And who, after all, complained the settlers, were the proprietors of East Africa but the British taxpayers?

If the government wanted to expand settlement in East Africa, Mr A. E. Atkinson told a protest meeting, ‘then by all means let us have our own poor farm laborers from England.’ The African Standard, the main vehicle of settler opinion, ran articles referring to the ‘Jewish invasion’ under such headlines as ‘The Country’s Death Blow’, ‘Goodbye East Africa’, ‘The Pauper Jews’, along with even more venomous references. This was a bargain struck behind closed doors in Downing St. ‘or was it in Lombard St?’, referring to the center of London’s business district. Church leaders joined in this shower of hostility to their government and what it was planning.

Sir Charles Eliot, the commissioner for East Africa, saw trouble ahead. Writing on November 4, 1903, he remarked that,

‘it is not likely that non-Jews will much frequent the Jewish settlement but their rights should be carefully reserved. When circumstances permit the persecuted to become persecutors they are apt to find the change very enjoyable and it would not be convenient for Christians if they were compelled to observe the Jewish Sabbath.’

On July 3, 1904, Herzl died unexpectedly. The shock to the Zionists was naturally great and the blow struck to the ‘Uganda’ scheme, which he had strongly supported, was soon to be felt. The three commissioners appointed by the Zionist congress set off for East Africa in December, 1904, returning to Europe in March, 1905. They were accompanied on their travels by a Foreign Office official and settlers. They had to do a lot of walking, camping in the forest, and listening to the trumpeting of elephants and the roaring of lions not too far from their tents. At one stage they encountered a Masai war party, with painted faces, wearing ostrich feather plumes and monkey fur anklets and threatening them with spears before retreating.

The visit left Kaiser discouraged, Wilbusch critical and only Gibbons somewhat hopeful that the plan could succeed. They filed their report and on May 22, 1905, the Greater Action Committee of the Zionist Congress, meeting in Vienna, recommended that the plan should not proceed. Meeting in Basel between July 27 and August 2, 1905, the 7th Zionist Congress, after studying the commissioners’ report, vote to drop East Africa: if there was to be a national home, it could only be in Palestine.

On October 19-20, 1905, there was a second pogrom in Kishinev, leaving 19 Jews dead and 56 injured. By this time the House of Commons had passed the Aliens Bill. Given royal assent on August 11, it was established as the Aliens Act, superseded by the Aliens Restriction Act of 1914, this in turn being replaced by the Aliens Restriction (Amendment) Act of 1919.

Balfour himself had supported settlement in East Africa. Writing the introduction to Nahum Sokolow’s History of Zionism, published in 1919, he said he had always been greatly interested in the ‘Jewish Question.’ In the early years of the 20th century, he wrote, ‘when anti-semitism in Europe was in an active stage, I did my best to support a scheme devised by Mr Chamberlain, then Colonial Secretary, for creating a Jewish settlement in East Africa under the British flag.’ There, it was hoped, Jews fleeing persecution in Europe might found a community ‘in harmony with their own religious thought.’

By 1905 the plans for Jewish settlement in Cyprus, Sinai and East Africa had all collapsed. Jews were still fleeing persecution in eastern Europe but Balfour was not willing to open Britain’s doors. Intermittent debate over the Aliens Bill continued in the House of Commons from May through July. The familiar themes included the loss of jobs to ‘foreign immigrants’, the ‘evils of overcrowding’, the cost to the taxpayer of supporting improvident newcomers and the government’s right to choose whom it allowed into the country, even in pressing humanitarian conditions.

Mr Forde Ridley, representing Bethnal Green, which had a substantial Jewish community living around Brick Lane, complained of,

‘a growing increase in the number of undesirable aliens flocking to our shores, which are already overcrowded, who are underselling our workpeople, turning them out of their homes and making their lives unendurable.’

He claimed that houses were being built ‘and put up for occupancy for which it is announced ‘no Gentiles need apply.’ After describing the filthy conditions he said he saw when visiting Jewish bakeries, Mr Ridley asked:

‘Are these the industries introduced by aliens which it is desirable we should foster and encourage? These aliens come and compete with the British working man and would drag him down to their own degraded level.’

Keir Hardie, the Scottish socialist, opposing the bill, spoke of ‘poor creatures’ being shot down in the streets of Warsaw ‘and other parts of Russia’ poverty-stricken human beings ‘who have been hunted down as beasts of prey’ and were now being condemned by the Aliens Bill to remain in a country ‘that does not know how to treat them.’

Balfour himself trod gingerly around the subject, avoiding the angry rhetoric that marked much of the debate but getting the same point across that, for a number of reasons, Britain needed to block the inflow of Jewish refugees. ‘If there was a substitution of Poles for Britons,’ he remarked elliptically on one occasion,

‘though the Britons of the future might have the same laws, the same institutions and constitution and the same historical traditions learned in the elementary schools, though all these things might be in the possession of the new nationality, the new nationality would not be the same and would not be the nationality we would desire to be our heritage through the ages yet to come.‘

As many of the ‘Russians’ heading for Britain were in fact Polish Jews, there could be no doubt about who Balfour really meant, despite his sophistry.

At one stage Balfour asked,

‘whether or not we were bound as a nation by our traditions or by common considerations of humanity to allow these strangers to become a portion of our own community, and if they choose to naturalize themselves, to claim the rights and privileges of British birth and citizenship?’

His answer to this rhetorical question was shaped in another typically circular rhetorical question, couched with qualifications:

‘Were we not justified in saying that that we had a right to exclude such persons until they should show not necessarily by the production of a large sum of money but in some way or other that they had an expectation of earning their livelihood, seeing that we by our own legislation were bound to support those who could not support themselves and to carry out those sanitary regulations the enforcement of which threw such a heavy burden on any community which had any more than a certain number of these poor immigrants to deal with.’

Twelve years later there was no talk of sanitary regulations and support for improvident immigrants when he handed Palestine over to the Zionists. What Britain would not allow within its own borders it did not even question when throwing open the doors to another land.

Balfour’s somewhat opaque personality tended to conceal what he really thought. He mixed socially with British Jews, including the Sassoons, but his references to ‘a people apart’ indicated that he could not quite regard even them as fully British. In the context of nationalism, imperialism, Christianity and the concept of the Anglo-Saxon ‘race’ this should not be so surprising.

The anti-alien legislation passed between 1905 and 1919 had the desired effect, of severely restricting immigration, including Jewish immigration, but in different forms the story has continued down to the present day. In March, 1938, the flight of German Jews soared following Anschluss, the German annexation of Austria. Between July 6-15, 1938, the delegates of 32 countries met in France at Evian-les-Bains, on the shores of Lake Leman, to discuss the Jewish refugee crisis.

Collectively they called themselves ‘the nations of asylum’ but as the discussions proceeded, only Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic, two of the poorest countries in the world, offered to open their doors wide to as many Jewish refugees as who could come. The rest shuffled their feet and refused to make anything more than minor adjustments to immigration quotas. Australia could not do more, and, with its ‘white Australia’ policy, did not want to import a race problem anyway (ignoring the gross racism of which the indigenous people of Australia were the victims); France, Holland and Belgium had reached saturation level; high unemployment precluded Canada from taking the refugees in – ‘none is too many’; Britain was not a country of immigration but was prepared to make space for 200 refugees in Kenya. The US was not even represented by a government official, but, rather, by a personal friend of President Roosevelt’s, Myron C. Taylor. The only adjustment it made was to assign its annual 30,000 immigration quota from Germany and Austria to Jewish refugees.

The British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, commenting on the refugee problem, said there was no territory in the British empire ‘where suitable land is available for the immediate settlement of refugees in large numbers although in certain territories small-scale settlement might be practicable.’ The unspoken exception was Palestine, which, occupied by Britain, was steadily filling up with Jewish refugees, legal and illegal, the occupier’s distinction.

After the Anschluss the British government actually tightened immigration procedures, thus preventing the entry of many Jewish refugees. In 1940 Jewish refugees were among the ‘alien immigrants’ interned in a number of camps: after the war, according to Louise London, British immigration policy ‘deliberately excluded Jews (and non-white immigrants) because it didn’t consider them assimilable.’ A Cabinet minister warned that admitting more refugees ‘many of whom would be Jewish’ might provoke strong reactions from ‘certain sections of public opinion.’

A condition of entry for such Jewish refugees as were admitted between 1933-45 was that they should not be a burden on the public purse, an issue that had been central to the debate on the Aliens Bill in 1905: as had been the case, Jewish charities stepped forward to give their guarantees.

By 1945 a permanent solution to the Jewish refugee problem was coming to rest on Palestine. The Zionists wanted unrestricted entry and did not want the refugees going anywhere else anyway, not that any ‘western’ countries were prepared to admit any more than a token number. President Truman’s call for 100,000 refugees to be admitted to Palestine greatly irritated Britain, almost bankrupted by the war, and already hard-pressed to meet the costs of its empire.

Roderick Balfour, the great-great-nephew of Arthur James, born in December, 1948, a banker and the current Earl of Balfour, is on record as supporting a two-state solution and has criticized the Balfour declaration over the non-fulfillment of the provision that ‘nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities’ in Palestine. ‘That’s not being adhered to’ he has said. ‘That has somehow got to be rectified:’ at the same time he described the Balfour Declaration as a great humanitarian gesture, stemming from ‘the appalling Russian pogroms at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.’

What the record shows is that when it counted, in the early 20th century, Arthur James Balfour did nothing to help Jewish refugees fleeing from these pogroms. He supported their settlement elsewhere in the empire, but not in his country. In its essence, the Balfour Declaration was born not of humanitarian intentions but imperial considerations, to do with the conduct of the war and the post-war settlement in the Middle East. Sentiment was the mask and strategic interests the reality.

Balfour’s rhetoric scarcely concealed his contradictions. He could speak with apparent emotion of Zionist aspirations while coldly dismissing the rights and interests of the Palestinian Arabs, Muslim and Christian. Regarding Jews as a ‘people apart’ – and one would have to think that in some sense this applied to British Jews as well as ‘aliens’ – his support for Zionism makes sense. As for his humanitarianism, one does not solve one humanitarian problem by creating another. Just as Balfour gained politically in 1905 by speaking against ‘alien’ immigration into Britain, so he gained politically in 1917 by speaking in favor of Zionism and Jewish settlement in Palestine. The long-term consequences of this ‘humanitarian’ gesture have been shattering.

Additional Sources:

Mwangi-wa-Githumo, ‘The Search for a Zionist settlement in Kenya 1902-1905’, in Ufahamu, A Journal of African Studies, January 1, 1983.

Report on the Work of the Commission sent out by the Zionist Organization to Examine the Territory Offered by H.M. Government to the Organisation for the Purposes of a Jewish settlement in British East Africa, London, 1905.

Destitute Aliens (Immigration) Act, House of Commons debate, February 11, 1893.

Elspeth Huxley, Nine Faces of Kenya: Portrait of a Nation, London, 1991.

Arnold White, ed., The Destitute Alien in Great Britain. A Series of Papers Dealing with the Subject of Foreign Pauper Immigration, London, 1892.

Reports on the Volume and Effects of Recent Immigration from Eastern Europe into the United Kingdom, presented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty, London, 1894, C7406.

A Voice from the Aliens, London, 1895.

Brian Klug, ‘The Other Arthur Balfour Protector of the Jews’, The Balfour Project.

Louise London, Whitehall and the Jews 1933-1948: British Immigration Policy, Jewish Refugees and the Holocaust, 2001.

Anne Karft, ‘We’ve Been Here Before’, the Guardian, June 8, 2002.