By Tsneem Mohammad

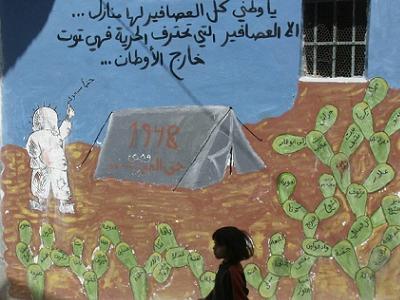

Like a sad symphony, being in exile composes a heart-wrenching note. Foreigners may choose to return to their countries whenever they wish to, but a person living in exile lacks this choice. The exiled is a label given to the Palestinian refugees who were forced out of their homeland into the Diaspora in 1948. They have no ID cards and they have been scattered all over the world awaiting the right to return to their land.

Sadly, Palestinians who live in Arab countries experience this “separation” or ghurba the most harshly. This term, “the exiled” – al-moghtaribin, was invented for Palestinians residing in those countries to haunt them with dark feelings of alienation and isolation.

In those Arab countries, you may live and work, but you may also be dismissed from your job without warning. At that point, you have to pack your bags and leave because you’re considered an illegal immigrant. Your residency in that country or the other is inferior to that of the nationalities, not to mention the country’s citizens. You are subservient and outcast because you are guilty of being Palestinian.

Being Palestinian means you have no country, no leadership and no one to stand up for you or defend you in your plight. You are on your own.

As a woman exiled from my homeland, Palestine is more of a complicated concept that it is a pain. It’s a concept invented for Palestinians exclusively consisting of various phases, each with its own lessons to be learned. Exile from the homeland molds a woman into an expert in life. Sometimes she’s a kindhearted teacher, at other times a strict one; a wise one, and at times a futile one.

As a child, I was born into an alien country whose people didn’t speak the same language as my parents, a country whose women dressed differently than my grandmother and its people eyed us in a manner different than others. It was then that the bud of exile and alienation grew within me day by day.

From the first day at school, we were labeled “the exiled” which had an eerie effect. At school, all girls who shared this label hung out together. Our place of meeting was under an olive tree which was situated on the school playground. It was there under that tree that we sat to support and strengthen one another. We collected some olives, pressed and ate them to get a scent and taste of our homeland, Palestine.

As we grew up, we tried to put together different incongruent pieces of our country together. We had images of a place called Palestine in our minds which we tried to assemble to form a puzzle.

Those images were formed as we listened to our parents talk about our homeland; from the letters they received from home, from the aromatic sage which was sent to us from home, from our grandmothers’ stories and our family photos. It was a challenging puzzle to form, yet we made all efforts to put its pieces together to see what our homeland, Palestine was like.

At times we were uplifted with joy and excitement, and sometimes we became distraught. But when we finally managed to put the pieces together, the image we formed was the best thing for an eye to behold. We memorized its small parts and took pride in retelling our stories to others. Like thrilled children, we retold our story until we were overcome with nostalgia. Palestine conquered our hearts just as exile had. Exile had empowered us, gave us a sense of identity, gave us hope, pride and anticipation.

“When we return to Palestine, we will see the most beautiful things ever. We will live in peace and our dreams will grow bigger.” That’s what my childhood mind told me. I was overjoyed when my family decided to return back to Palestine. Of course, we didn’t return to our original hometown, Isdud.

We returned to Gaza after the Oslo Accords were signed and the first Palestinian Intifada was forcibly ended. To my dismay, I wasn’t prepared to see the shocking reality which I found upon my return – a form of exile harsher than the one I left behind. My homeland had become a slain bird. I said to my mother, ‘If they’d given us a piece of it, a wing or something, we could have restored it back to life. Why didn’t they give us just a wing, mom?’ Mom was silenced letting her tears speak. I was unable to fully understand those tears back then, but the passing of days and the shedding of more tears was sufficient to provide a desperately-needed explanation to what I had failed to fathom earlier.

That’s the story of how we became strangers in our own land. My mind retreated back to the years of exile outside Palestine. In a way I longed to go back there. I had a perfect picture of Palestine in my mind and which was now shattered to pieces. As the mysteries of life began to unfold before me, my homesickness intensified within to greater depths. In childhood, it was a fancy; in adolescence a homeland, but it adulthood a heavy burden!

As an adult, when you become alienated from your homeland, you carry it in your heart wherever you go. It only exists inside you. You see it in the eyes of your fellow exile peoples who huddle together to preserve a sense of home. You see it in the minds of the exiled resistance fighters, hear it in the chants of freedom songs and feel it in the empathy shown towards you from others. In exile, home was harder to fathom; yet was more enchanting, it became a burden; yet a priceless place, it grew farther in distance; yet was pristine.

In exile, homeland extends within until it conquers every corner of the soul. It seems closer symbolized in the Palestinian Kuffiya or flag we wrap around ourselves. In our forced exile, homeland ceases to feel so harsh. We don’t feel the injustice of the world towards us, and world tyranny vanishes. Exotic feelings take over our hearts and we take pride in resistance and become obsessed with our seemingly beautiful exile. We whole-heartedly cherish our homeland and the values of honor and pride which our parents inculcated into us. We defy time by holding on to our memories.

– Tsneem Mohammad was born in 1985. She is a Palestinian refugee originally from Isdud, Palestine. She worked as a screenplay writer and producer at Al Aqsa satellite channel. She also write articles on Palestine that are published on Aljazeera Arabic and locally in a social magazine called ‘Al Saada’. She contributed this article to PalestineChronicle.com.