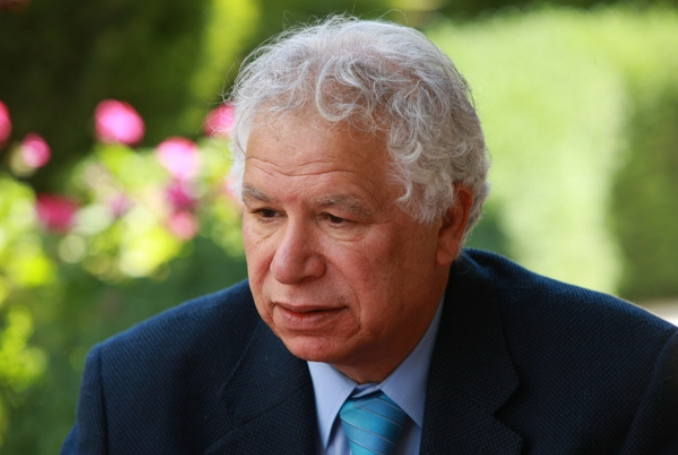

Mourid Barghouti is a renowned Palestinian poet who passed away on Sunday, February 14, at the age of 76, in the Jordanian capital Amman.

Born in the Palestinian village of Deir Ghassanah, near Ramallah, in the West Bank, on July 9, 1944, Barghouti spent most of his life in exile.

The legacy that Barghouti left behind is extremely rich, not only because he was one of the most articulate defenders of the Palestinian cause, but because his writing has encapsulated the collective agony and sumoud, steadfastness, of the Palestinian people everywhere.

Aside from the fact that he was a Palestinian icon in the fields of poetry and prose, his life story also served as a representation of the Palestinian shataat – diaspora. Barghouti’s journey spanned many countries, including Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt.

Although his writing was rich and diverse, his autobiography “I Saw Ramallah”, published in 1997, achieved international status and was translated to many languages.

In 2009, Barghouti’s second autobiographical volume, “I Was Born There, I Was Born Here” was published, and translated to English in 2012.

Additionally, Barghouti has 12 poetry collections published throughout the years.

Below are selected excerpts from Barghouti’s writings.

‘‘I Saw Ramallah’

I tried to put the displacement between parenthesis, to put a last period in a long sentence of the sadness of history, personal and public history. But I see nothing except commas. I want to sew the times together. I want to attach one moment to another, to attach childhood to age, to attach the present to the absent and all the presents to all absences, attach exiles to the homeland and to attach what I have imagined to what I see now.”

‘I Was Born There, I Was Born Here’

During this wait too I retreat into my shell.

I’m alone with sounds and sights, with my private questions marks and exclamation marks.

It’s as though a huge deserted warehouse had opened its doors to me or I’d become my own museum and its only visitor after the guards have gone home to sleep and locked me in.

I find fault with my acts, or the fewness of them, or the total lack of them, or their total ineffectiveness. I confront my faults like a courageous hero of the stage or make up hypocritical excuses for myself like any coward.

I become a severe judge who refuses to accept the argument of the self, lovers, or relatives, and, in the same instant, I become the conniving, bribable judge who flees difficulties in favor of peace of mind.

I open my small eyes to the ‘intellectual’s diseases’ that have taken root in my body.

I say to myself, I’m just a poet.

Without Mercy

There is a sweet music,

but its sweetness fails to console you.

This is what the days have taught you:

in every long war

there is a soldier, with a distracted face and ordinary teeth,

who sits outside his tent

holding his bright-sounding harmonica

which he has carefully protected from the dust and blood,

and like a bird

uninvolved in the conflict,

he sings to himself

a love song

that does not lie.

For a moment,

he feels embarrassed at what the moonlight might think:

what’s the use of a harmonica in hell?

A shadow approaches,

then more shadows.

His fellow soldiers, one after the other,

join him in his song.

The singer takes the whole regiment with him

to Romeo’s balcony,

and from there,

without thinking,

without mercy,

without doubt,

they will resume the killing!

(From: Midnight and Other Poems, 2008. Translation: Radwa Ashour)

(The Palestine Chronicle)