By Benay Blend

In a recent Facebook post, author Susan Abulhawa said that it’s hard not to believe that “with all their privilege and resources, cannot imagine a single alternative to educating their children except to reopen schools in the midst of a terrifying pandemic, which will surely infect and kill students and educators alike.”

As America ponders whether to fully open schools, President Trump has threatened to withhold federal funding from institutions that don’t fully reopen in the fall, despite surging cases of Covid-19 across the country. Although he has compromised somewhat on wearing masks to prevent the spread of COVID, he has not budged on the reopening of schools, partly because he wants the country to go back to business as usual, back to “normal,” even if it is not.

The private school attended by Trump’s son, Barron, has not yet decided on a plan of action, but whether its on-line or hybrid learning St. Andrew’s Episcopal School will be fully prepared. “The president now has to face what every other parent in America and every other teacher in America is grappling with right now, which is: In the midst of a pandemic, how do schools keep their kids and their faculty safe?” Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers, said in an interview. “It’s about safety, not bluster. It’s about a plan and resources, not threats.”

Her hope that the President will develop a “scintilla of empathy and consideration for what Americans are going through now that he is experiencing it himself” will likely go unfulfilled. For centuries children in America and other countries have experienced unequal education and much more.

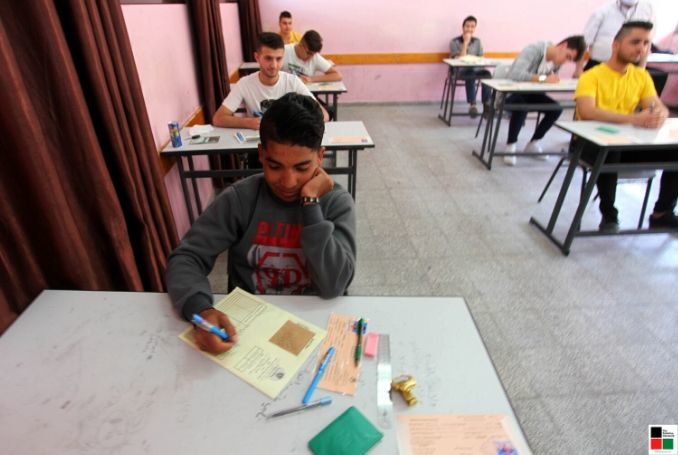

The first Palestinian Intifada began in 1987 after nearly 40 years of brutal Israeli occupation. More than a “knee-jerk reaction,” Sonja Karkar writes, it was a “united demonstration” of “continuous …grassroots” struggle that continues to this day. For Majed Abusalama, living under lockdown in Germany, where she now resides, brings back memories of his Gaza childhood during the first Palestinian uprising.

By the time that the Intifada ended, Abusalama was a school-age boy. He remembers that universities and schools were closed, leaving a generation of Palestinian youth deprived of an education. Nevertheless, he affirms that despite the many hardships, the Israelis could not “bring down the Palestinian spirit.”

“All across historic Palestine, popular resistance committees were established which coordinated various activities to provide for the people. Trade committees organised strikes; health committees established makeshift clinics; educational committees set up underground classes. Everyone put in whatever effort they could to help their community and no one was left without communal support,” much like mutual aid networks of today.

Though life was very difficult, his parents recall the Intifada as a “time of liberation, often saying, ‘We did not give up on our resistance. We did not become subdued victims.’” In fact, wherever grassroots struggle exists today, Palestinians helped to set the model.

As Ramzy Baroud observes, Palestinians are still in lockdown–“those held in besieged Gaza or those trapped behind walls, fences and checkpoints in the West Bank” (These Chains will Be Broken: Palestinian Stories of Struggle and Defiance in Israeli Prisons, 2020, p. 7). Yet their story is still that “of resistance and sacrifice, of defiance and sumoud, of steadfastness” (p. 8), Baroud writes, all qualities that serve well in the struggle against both enemies—Israel and the virus.

Thirty years before the Intifada, there was Cuba’s national literacy campaign during which, writes Mark Abendroth, “education and ideas” became the “primary weapons for defending the Revolution.” Although the Literacy Campaign would not be in full swing until 1961, its “seeds…were sewn” by the Rebel Army which conducted literacy drives, initiated by Che Guevara.

In the midst of revolution, military barracks were converted into schools and 10,000 new classrooms were opened. In 1961, the literacy campaign mobilized under young maestras (women teachers) who are honored in a documentary of the same name.

“In a country where the urban and rural poor had long been denied access to education,” declares Sujatha Fernandes, “literacy was empowerment. For the counter-revolutionaries who wanted to see Cuba return to the status quo, teaching literacy to the poor was an affront to the class order.”

The literacy campaign is important to remember today, given the challenges of the pandemic. Accordingly, there is much wisdom in these words of the former enslaved Frederick Douglass: “To deny education to any people is one of the greatest crimes against human nature. It is to deny them the means of freedom and the rightful pursuit of happiness, and to defeat the very end of their being.”

There have always been alternatives to mainstream public education. In Survival Schools: The American Indian Movement and Community Education in the Twin Cities (2013), Julie L. Davis describes the American Indian Movement’s (AIM’s) community education efforts that began in the early 1970s and lasted until 2008.

In 1972 the organization established the Heart of the Earth Survival School in Minneapolis and the Red School House in neighboring St. Paul. AIM’s survival schools met in various locations where they sought to ameliorate academic failure on the part of Native children by offering cultural courses along with academics.

Similarly, as the 1964 Mississippi Summer Project got underway, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) proposed the establishment of Freedom Schools for Black youth who needed more than mainstream schools. Divided into two parts–“Citizenship Curriculum” and the “Guide to Negro History”—the courses were designed to help students put their personal experiences with racial discrimination into a broader context. For many students, the summer of 1964 was life-changing, paving the way not only to higher education but also an entry into the Movement.

What ties all of this together, and makes it relevant today, is the need to learn from these community-based, culturally appropriate schools. With all of the newly established mutual aid networks that sprang up to meet the COVID challenge, it seems that some planning could be diverted to education.

As Abulhawa notes:

“During the First Intifada, Israel closed down Palestinian schools for two years. They did it to punish the natives, for whom education was seen as a means of survival. It didn’t take long before every other Palestinian house or apartment became a schoolhouse, and a system of communication with whistles and calls from rooftops was established to protect and warn each other when the zionist military rolled in.”

Learning has been an important component of every revolution, perhaps never more so than now. In a blog post entitled “Guns without Political Education is like a Journey without Direction,” Ahjamu Umi reiterates the need for political education.

“Africans (Black people) everywhere,” he says, “are expressing joy and support for the presence of this Not F—ing Around Coalition (NFAC),” a group of armed Africans who “display weapons and demonstrate symbolic resistance against white supremacy.” Since nothing changed because of this symbolic action, he concludes that “guns, no matter how many of them, without organized political education guiding the usage and existence of the guns, is never a good formula.”

Without organization, and the political education that comes with that, Umi writes, there can be only efforts at “theater to make us feel better about the system continuing to dominate our lives.” Whether its political education organized within a specific group; an alternative plan to educate the community’s youth in a safe, nurturing environment; or self-education, the time is ripe both here and in Palestine to teach our young people how to imagine a different future.

– Benay Blend earned her doctorate in American Studies from the University of New Mexico. Her scholarly works include Douglas Vakoch and Sam Mickey, Eds. (2017), “’Neither Homeland Nor Exile are Words’: ‘Situated Knowledge’ in the Works of Palestinian and Native American Writers”. She contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.

– Benay Blend earned her doctorate in American Studies from the University of New Mexico. Her scholarly works include Douglas Vakoch and Sam Mickey, Eds. (2017), “’Neither Homeland Nor Exile are Words’: ‘Situated Knowledge’ in the Works of Palestinian and Native American Writers”. She contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.