By Jeremy Salt

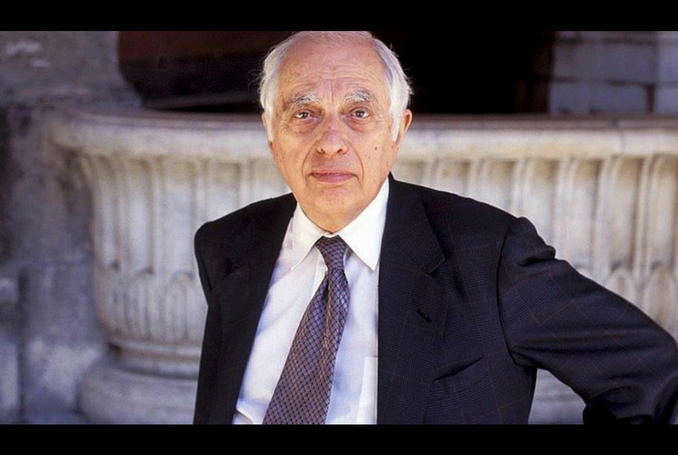

So Bernard Lewis has finally died, ‘finally’ because at the age of 101 it was beginning to seem that he never would.

Born in 1916, Lewis was educated in the scholarship of the 19th century and early 20th orientalists, the mustashriqun as they were called by Arab historians, among them Sylvestre de Sacy, Snouck Hurgronje, Ignaz Goldziher, Joseph Schacht and William Muir, whose works on the life of Muhammad and the caliphate were underscored with the belief that ‘the sword of Mahomet and the Coran are the most stubborn enemies of Civilization, Liberty and Truth which the world has yet known.’ A slightly older contemporary was Hamilton Gibb, the acknowledged doyen of Middle Eastern studies in the West for the first half of the 20th century.

Lewis began to come into his own in the 1950s. As well as Arab history, he wrote on Turkey, where he is remembered with gratitude for saying in France that he did not believe the massacres and mistreatment of the Armenians in 1915 amounted to genocide, which he described as only the Armenian version of events. Accused of breaching the law, he was prosecuted, found guilty, fined a nominal amount (one franc) and ordered to pay the legal costs of the Armenian plaintiffs.

Lewis inhabited two Arab worlds. Except for the rarefied company he kept (his admirers in Israel, King Hussein of Jordan and other Arabs rulers whose true and only constituency lay in the West) he had no time for the modern Arab world, its problems, its untidiness and corruption and the causes and aspirations of its peoples.

The Arab world where he clearly felt at home was one which he could never visit, because it had disappeared into history. This was the world of the Abbasid and Umayyad caliphates, of the Bayt al Hikma (House of Wisdom) in Baghdad, of the glories of Islamic Spain, of the exquisite Alhambra palace and its gardens, of learning and scholarship, of poetry and music and the works of the great Arab historians and philosophers.

While Lewis wrote general studies of Arab history, as well as articles and books on Muslim-Jewish relations, questions of color, race and slavery in the Islamic world and the history of the Ismailis, especially the deeds of the Assassins, as an increasingly influential historian by the 1950s, he could hardly ignore the pressing issues of the day. Out of the chrysalis of current events came the political Bernard Lewis.

His binaries simplified understanding of the Middle East, Islam and the West’s relationship with both. There was Christendom on one hand and Islam on the other, Europe on one hand and Islam on the other, the West on one hand and the Middle East on the other, an Arab/ Islamic civilization on the one hand and Western civilization on the other. As mis/represented by him, not one of these binaries conformed to the nuances of interdependence in history, between the wars, but they did serve a political purpose. The West and the ‘clash of civilizations’, in particular, as verbal constructs, had the effect, even if they were not deliberately conceived with this in mind, of masking the strategies and wars of specific members, usually Britain, France and the United States.

The ‘clash of civilizations’ did not come from Samuel Huntington but Bernard Lewis. In the 1950s and 60s, he presented the collision between the imperial West and Arab nationalism as the consequence of an Arab inability to adjust. ‘The Arabs’, he wrote, as if they were all one and the same, were being offered variations of modern civilization and had to decide which one to accept.

The choice would involve them ‘merging their own culture and identity in a larger and dominating whole.’ In other words, a distinctive Arab culture and identity would have to disappear but the Arabs would benefit from what was on offer, from the practical artefacts of ‘western civilization’ to the abstracts of democracy and respect for human rights, both practiced at home by Western governments but eschewed abroad, where bombs, missiles and tanks were regarded as more effective agents of change than democracy.

If Arab civilization was in crisis – Lewis is writing in the early 1960s – this was because it was finally reacting against ‘the impact of alien forces that have dominated, dislocated and transformed it. He is not talking about the impact of wars but about the impact of abstracts, such as western concepts of government and human rights. ‘We’ – his intended audience is primarily Western – would be better able to understand the situation by viewing the ‘present discontents’ of the Middle East ‘not as a conflict between states or nations but as a clash between civilizations.’

By the 1990s the wave of Arab nationalism had long since receded into the distance. The nationalist threat had been replaced by the Islamic threat but the source of the problem faced by the west remained the same in the Lewis view: ‘we’ (again) are facing ‘a mood and a movement far transcending the level of issues and policies and the governments that pursue them.

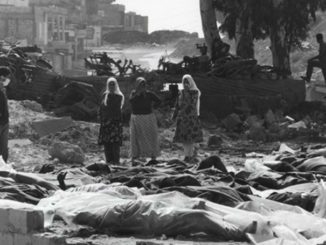

This is no less than a clash of civilizations – that perhaps irrational but surely historic reaction of an ancient rival against our Judaeo-Christian heritage, our secular present and the worldwide expansion of both.’ Muslim anger was born not of the theft of Palestine, not of the annexation of Jerusalem, not of the wars that had killed or dispossessed millions, but frustration and rage at a civilizational power Muslims could neither overcome nor live with. The great human tragedy of Palestine was sneered away as ‘the licenced grievance.’

In short, ‘they’ve been hating us for centuries and it’s very natural that they should. You have this millennial rivalry between two world religions and now from their point of view the wrong one seems to be winning.’ If many Muslims seemed hostile to the West or ‘dangerous’ it was not because ‘we’ need an enemy ‘but because they do.’

This version of modern Middle Eastern history enabled the US, its ‘western’ and gulf allies and Israel to dump responsibility for their crimes on to the shoulders of the victims. What the West had done, the wars, the massacres, the coups, the assassinations, the plunder and theft of Palestine, could be pared down to someone else’s fault, either ‘the Arabs’ or the Muslims depending on the period of history Lewis was writing in or about. Yes, the West had made mistakes, but only with the best of intentions, and anyway, none of them was sufficient to explain the rage of Arabs and Muslims.

Over decades Lewis told the US government, Congress, the New York Times, the Washington Post, The Times, CNN, the conservative and neoconservative think tanks and Commentary magazine, anyone willing to listen and reproduce his views exactly as uttered, what they wanted to hear. He was the expert, after all. No-one understood the Middle East like Bernard Lewis, apart from Fuad Ajami, who peddled the same comforting messages about the ennobling role of invading Western armies, and if Professor Lewis did not know the truth about the Middle East, who did? His was the authoritative voice, to be heard reverently and not questioned.

After 9/11 it seemed that Lewis and Huntington were right and Frances Fukuyama was wrong in proclaiming ‘the end of history.’ History had not quite come to an end. It still had to get through the ‘clash of civilizations’, the all-purpose explanation for ‘what went wrong’ and ‘why they hate us.’

In the Lewis view the wars launched by the West and Israel had nothing to do with ‘what went wrong.’ Rather like a recalcitrant teenager, Muslims were simply refusing to adjust to new circumstances. So little attention did Professor Lewis pay to the wars launched by the collective West as a reason for Muslim anger that they might have been irrelevant or might not even have happened. Shaken out of their complacency and their ‘illusions of superiority’, western civilization clearly having proved superior, Muslims burn with resentment and rage, even hatred, not because of anything the west has done but because of what it is.

By the 1990s Lewis was coupling terrorism with migration. In an address at the American Enterprise Institute in 2007 he talked of three ‘waves’ of Muslim attacks on Europe. The first was the Arab invasion of the 7th century, the second was by the Ottoman Turks, beginning in the 13th century, and now ‘in the eyes of a fanatical and resolute minority of Muslims the third wave of attack on Europe has clearly begun. We should not delude ourselves as to what it is and what it means. This time it is taking different forms and two in particular, terror and migration.’ Unlike the effete West ‘they’, the resolute Muslims, know what they are doing, in addition to which they have demography on their side, because of migration and the size of Muslim families.

This coupling of terrorism with migration was heinous, a slur on all Muslims living in Europe. In every country they want nothing more than a peaceful life for themselves and a future for their children. They are not the all-purpose Lewis ‘they’ because while bonded by religion, to a greater or lesser degree (or perhaps not bonded at all), they are divided by geographic origin, language, color, sect and ethnicity.

The number who break the law, who carry out terrorist attacks, which cannot be justified by Islam anyway, or who want to impose their order on Europe, is infinitesimal by comparison but this doom-laden presentation had Lewis’ audience at the American Enterprise Institute calling for more. The terrorist Muslim was just what they wanted to hear.

Lewis constantly patronized and demeaned Arabs and Muslims while claiming to be their friend and speaking for them in their interests. This is a defining characteristic of orientalistic scholarship. Ultimately knowledge is used against the peoples in whose histories it is accumulated. Underneath the patina of learning, Lewis the scholar was intensely political, constant in his support for governments that did great damage in the Arab and Muslim worlds.

He spoke against all great modern Arab and Muslim movements and causes. Jewish and a committed Zionist, he was the friend and adviser on tap for every Israeli president and prime minister, remaining completely unruffled by the gross crimes they were committing. American politicians hung on his every word. He was their high priest. He authorized them, he confirmed them, he sanctioned every crime they committed in the Arab world and broader Muslim world and when the time came he answered his own question of ‘what went wrong?’ by blaming the victim, whether the Palestinians or Arabs and Muslims more generally.

Edward Said could not stand him and the dislike was returned in equal measure. In Said’s words, Lewis preached scholarship but practiced politics. The biographies will soon start appearing. Scholarly appraisal of the books and articles written by Lewis will form one strand. Another will be what the archives reveal of Lewis’ dealings with governments, the advice he gave and how it influenced their policies. He has gone, finally, but it will be a long time before he is forgotten.

– Jeremy Salt taught at the University of Melbourne, at Bosporus University in Istanbul and Bilkent University in Ankara for many years, specializing in the modern history of the Middle East. Among his recent publications is his 2008 book, The Unmaking of the Middle East. A History of Western Disorder in Arab Lands (University of California Press). He contributed this article to PalestineChronicle.com.